A pop-up second-line procession along Claiborne Avenue, from July 2018.

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberWhere North Claiborne Avenue runs through the 7th Ward and Tremé neighborhoods of New Orleans, old men play dominoes, a farmer sells watermelons from the tailgate of his pickup truck, a young man washes cars and a man in checkered cook’s pants walks alongside a woman in a hotel maid’s uniform, both coming home from a day’s work in the nearby French Quarter. All of this activity happens daily beneath the wide elevated highway that parallels Claiborne’s street-level lanes.

For as far as the eye can see, the concrete pillars that hold up the elevated interstate are painted with the images of oak trees. It’s like a grove of concrete trees.

Once, there was a grove of real trees here. More than 300 massive live-oak trees, which stood in four rows along a wide grassy median on North Claiborne that served as a picnic and play area for the historically black neighborhoods around it. Before the highway went up in the 1960s, some 326 black-owned businesses also thrived along the stretch, making it a commercial and cultural destination for black families across the Deep South.

“It was drop-dead gorgeous, an oasis, a place to meet friends,” says Jessie Smallwood, 85, whose family often headed to Claiborne. “You were underneath trees. You knew people a block over.”

For nearly a half-century, people have mourned how this raised section of federal highway sliced through more than two miles of the city’s historically black neighborhoods, dooming Claiborne Avenue’s thriving business corridor. (Tulane’s School of Architecture has an image gallery that juxtaposes before/after pictures of the Corridor.)

Today, the outermost pillars along this stretch of Claiborne Avenue are painted to look like trees, while about 40 of the inner pillars are the canvas for original paintings by some of the city’s finest artists. They were created as part of a project called “Restore the Oaks,” spearheaded by painter and teacher Richard Thomas through the city’s New Orleans African American Museum of Art and Culture.

The result is an open-air art gallery that reflects the live oaks, people and culture of Claiborne Avenue, Tremé, the 7th Ward and New Orleans as a whole. Those strolling under the elevated highway on ground-level asphalt can walk past both Charlie Johnson’s and Charlie Vaughn’s images of Big Chief Allison “Tootie” Montana, the famed Black Masking Indian who lived a few blocks away. They can view a detailed image of a typical jazz funeral, painted in by Nat Williams, who works as a barber nearby.

“We were given sour lemons and what happened? We kept our culture. We evolved,” says Mona Lisa Saloy, a highly celebrated poet and English professor who is active in the neighborhood.

The Claiborne Corridor pillars have been painted to honor luminaries from New Orleans' African-American community. In this view are jazz legend Louis Armstrong (top right) and Alice Thompson (bottom left), a pivotal civil rights figure who worked to desegregate local businesses and bus terminals throughout the South.

The pillars are just one of the ways that the neighborhood has sought to make the best of what was forced upon them. Whenever social aid and pleasure clubs pass underneath the highway, during funerals or Sunday-afternoon second lines, horns point upward and play a triumphant call-and-response flourish. Inadvertently, highway crews fashioning this concrete box created a makeshift urban cathedral that broadens a brass band’s sound and sends it across the neighborhood. Saloy describes the effect as “joy multiplied.”

“It is the soundtrack of our lives and we are not letting it go,” says Saloy. Over the past few years, she and her neighbors have gone through a contentious debate over whether to keep what they collectively call “the bridge.”

But, instead of bringing in the bulldozers yet again, the concrete grove will remain in place according to a different vision — the recently released Claiborne Corridor Cultural Innovation District Master Plan, rooted in the ideas and desires of residents.

Informed by a series of 11 design charrettes held with residents and architects from May 2017 to February 2018, the master plan sets out to beautify the corridor while increasing jobs and economic stability through innovations such as a marketplace built with green infrastructure, which will run within a 25-block segment of the corridor.

Cosmetic work on the corridor has already begun, as part of a demonstration phase made possible thanks to an $820,000 construction grant from the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Economic Development Administration, matched with operational support from Ford Foundation, Chase Global Philanthropy, Surdna Foundation, Kresge Foundation and Greater New Orleans Foundation. Through a contract with the city, fiscal sponsor Foundation For Louisiana has raised money and helped to form a separate entity, Ujamaa Economic Development Corporation, that runs the daily operations of the Claiborne Innovation Corridor. Construction on the public market is slated to begin early in 2019 and wrap up by that fall.

The community-organizing work, on the other hand, started long before the charrettes and will be necessary long after this demonstration phase of construction ends. Residents are determined to shape future phases of the corridor, claim a fair share of projected economic opportunities and prevent the widespread displacement of longtime inhabitants — a feared but too-frequent outcome of rising neighborhood investment.

As a native and current resident of the 7th Ward, Asali DeVan Ecclesiastes lives and breathes the history and culture reflected in the painted concrete pillars. Today, her office window looks out onto Claiborne Avenue and the concrete structure that divided her childhood neighborhood. From her vantage point, the artwork, parades and festivals are evidence of how the bridge’s neighbors have incorporated the bridge into their lives.

“Anybody that comes out here on a Sunday knows how this space is used for community. We just take it back with our feet, with our music, with our art,” says DeVan Ecclesiastes, who has played a key role in crafting and implementing the new master plan, initially as the city’s program manager for the Claiborne Corridor and now as director of strategic neighborhood development at the New Orleans Business Alliance.

“We reclaim [the corridor],” she says. “And now this project is an effort to formalize that reclamation and to transform at the same time.”

An avid student of area history, DeVan Ecclesiastes also knows the larger arc of her project, which dates back 40 years. It’s rooted in a landmark 1976 report called the I-10 Multi-Use Study, conducted by the Claiborne Avenue Design Team, which included noted African American leaders Rudy Lombard and Cliff James and was rooted in the activism of the Tambourine and Fan club, a neighborhood education and cultural group whose members, many of them children, traveled to City Hall to advocate for Claiborne Avenue improvements.

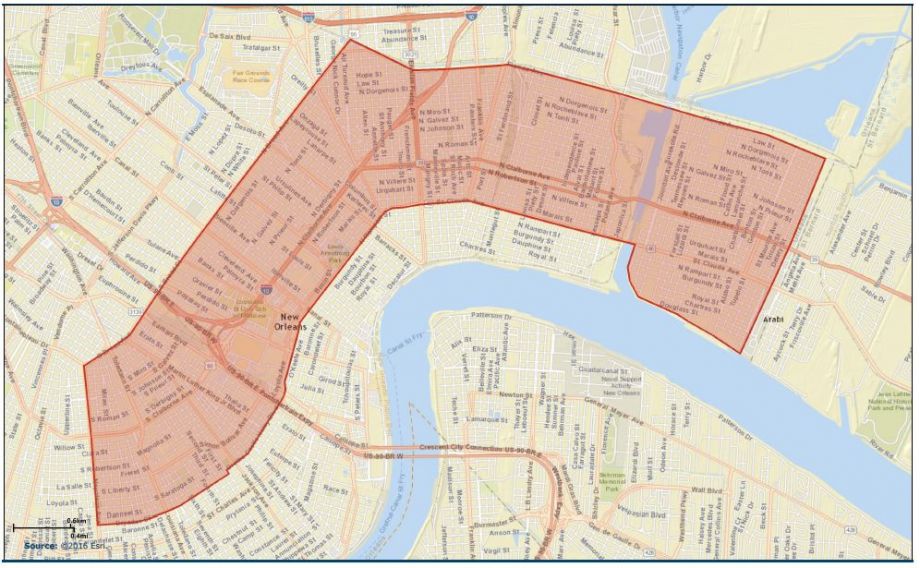

A map of the Claiborne Corridor. (Credit: Esri)

In the report’s introduction, Lombard, a gifted and influential writer, began: “We are no longer at home in our cities. They are too large and too disintegrated to reflect our humanity.” He decries how the freeway divided communities, untethering people from schools and each worker’s job, “which may have no noticeable relationship to his community or to the rest of his life.”

Lombard, like DeVan Ecclesiastes, believed that the structure that tore apart neighborhoods needed to be completely re-thought, to help spur a resurgence of the most elemental concept behind cities, which were once sought out because people realized that living near others had economic and cultural advantages. If done right, Lombard wrote, what was built underneath the concrete, car-centric edifice would promote biking, walking and interacting and cooperating with others, making cities once again “conducive to enjoyment of life.”

The corridor’s renaissance is also tied to a post-Katrina period when it was a prime discussion point. For a while, during that time, demolition of the interstate above Claiborne seemed increasingly possible, at times inevitable.

The idea of demolishing this raised portion of Interstate 10 that follows Claiborne was included in some of the city’s earliest rebuilding plans drafted after Hurricane Katrina. From there, two strange bedfellows latched on to the concept: preservationists who saw the freeway as a scar upon the urban landscape, developers who saw it as a real-estate boon.

The tear-down project was a no-brainer to John Norquist, then head of the Congress for New Urbanism and a former mayor of Milwaukee, who had removed a stretch of elevated highway in that city while in office.

“The data and analysis show that Claiborne doesn’t need to be a freeway,” Norquist said, referencing his group’s 2010 report that had outlined why the expressway should be taken down. Included in the findings were state traffic data showing that the elevated section of Claiborne was basically being used as a shortcut between neighborhoods, for short trips that averaged only 1.6 miles.

At that time, the plan to tear down seemed like a slam-dunk for urban planners. In the fall of 2010, the U.S. Department of Transportation and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development jointly awarded the city of New Orleans a $2-million federal planning grant for a Claiborne Corridor Study with a goal to “reconnect a neighborhood divided by an elevated expressway.” Even today, some residents feel like the process, its design and its execution is out of their hands, because of undue influence from the project’s earliest champions, who came from influential sectors of the city.

New Orleans City Council Member Kristin Gisleson Palmer captured the sentiment of the time as she recalled her childhood experience with the raised expressway, at a December 2011 forum about the corridor hosted by the Congress for New Urbanism.

“I just remember driving with my parents and turning onto Claiborne. And then the sun was immediately blocked out. As a child, I remember thinking, ‘How horrible it that?’” Gisleson Palmer says. “And I think we all feel that way when we turn onto Claiborne — it’s the emotive response that this huge, monolithic thing elicits to us.”

Gisleson Palmer says that she didn’t think of the process as reversible until after Katrina, when people began positioning demolition as part of the city’s recovery. “Sometimes you have to tear down to rebuild. This [was] one of those examples,” says Gisleson, who shifted gears once she heard that residents could not reach a consensus to demolish the structure.

“We don’t build a culture to be tourist toys. It’s our culture. It’s a treasure.”

As part of the 2010 federal grant, residents and stakeholders met for nearly a year. Among those who attended the workshops and planning meetings was Ed Buckner, 58, who lives nearby on Elysian Fields Avenue, where his house is the home base for both the Big 7 Social Aid and Pleasure Club and the Red Flame Hunters, a child-teen tribe of Black Masking Indians, commonly referred to as Mardi Gras Indians.

Buckner says that some people came to the meetings hoping to restore the glory days of Claiborne.

“Their plan was to tear down the bridge and bring the trees back,” he says. But he couldn’t see how the corridor of black-owned businesses would ever return to what it was.

Instead, Buckner and others seized on maintaining the culture that had continued to flourish on Claiborne even after the highway was built.

“It is not a thing of beauty, but it is ours,” Buckner says, explaining how, once the construction dust cleared, residents had returned to Claiborne to gather again, underneath the ugly concrete and steel. Old men once again played dominoes. Music rose. Black Masking Indians in bright feathers and intricately beaded suits chanted and struck their tambourines. People clowned around, discussed the day’s events and danced. Often someone drove up in a pickup that held a grill in the back and cooked a few rows of hot sausage and hamburgers.

When Saloy looked at the data assembled for Claiborne Corridor planning meetings, she wasn’t pleased with the level of traffic projected to travel along Claiborne at ground level if the freeway were demolished. With a grimace, she envisioned, the projected 10,000 cars jamming city streets, complete with 18-wheelers and rumbling dump trucks. Economic data was even more alarming, she says, noting that other cities had seen exponential increases in housing costs after freeways came down and were replaced by greenways, markets and new developments.

An instructive example would come later, from a few miles away, after St. Roch Market, damaged and shuttered after Katrina, reopened as an upscale food market in 2014. Taxes on nearby properties taxes tripled and even quadrupled, according to DeVan Ecclesiastes.

The results of those discussions were captured in the “Livable Claiborne Communities Study,” a report published after the workshops and meetings supported by the 2010 planning grant. That report contained multiple scenarios, some in which the I-10 overpass stayed and some in which it came down.

In the end, after the Livable Claiborne process was complete, it became clear, through surveys, focus groups and public discussions, that there was no consensus to demolish the bridge. Instead, neighbors opted to keep speculators and displacement at bay by holding on to their hulking overhead neighbor. “You take the monster away and it will be total gentrification. People will build things and they will not build them for us,” Saloy says.

It was a tough decision. For some, the deciding factor was the estimated $300-million demolition price tag, which was required to demolish the bridge structure and re-design the city streets that would carry re-routed traffic. People decided that they’d rather see that money spent to stabilize the existing neighborhood with jobs, transportation and flood protection.

“The split was about 50-50 between those who wanted the bridge to come down and those who didn’t,” DeVan Ecclesiastes says. “But 100 percent said that we need better jobs; 100 percent had environmental concerns; 100 percent said that we need to be able to stay here in this, our neighborhood.”

To retain existing residents requires the kind of investment and economic opportunity that has long been absent in the communities that line the Claiborne Corridor. Though New Orleans is a majority-black city where minority-owned businesses make up 36 percent of all metro-area firms, those businesses only received 2 percent of all business receipts in 2012, according to a study by The Data Center.

The Claiborne Corridor Cultural Innovation District Master Plan is expansive, going far beyond job creation, including proposals to provide residents with access to financial training, technical assistance, investors and expertise from more seasoned business people working in the same sectors as ambitious younger entrepreneurs. For instance, scholarships for a Community Development Finance certificate program at the University of New Orleans (UNO) provide a way for neighborhood entrepreneurs to present their business plans to a group of potential investors.

The plan’s goals also include improved health and public-transit outcomes, with health outreach workers and small neighborhood vehicles called “circulators” that can pick up neighbors for doctor’s appointments.

Stormwater management was residents’ second-greatest concern. The plans show bioswales, holding ponds and rows of live oak and cypress trees. Notably, it also calls for development of a drainage system able to divert up to two million gallons of water annually into canals — from the profusion of water that pours like waterfalls off of the interstate during tropical rainstorms, flooding nearby neighborhoods.

The plan also calls for spaces for children to play and learn, and seeks to address housing through a range of proposed policies including an innovative mechanism that holds onto city-adjudicated properties within the corridor. Instead of being auctioned to private buyers and gentrification-fueling developers, the city would funnel the tax-delinquent properties to selected non-profit developers, who will repurpose them to add affordable housing to the neighborhoods.

Cultural preservation is pivotal, enmeshed within every goal for the Corridor.

“Keeping people here is the most important part,” DeVan Ecclesiastes says. She believes that the distinct culture of New Orleans’ black neighborhoods is also the key to innovating and creating opportunity, since it’s long been a fascination of filmmakers, artists, musicians, chefs and tourists from around the world.

The key is to make sure that those who create the culture of New Orleans can benefit from their talents, said Saloy. “We don’t build a culture to be tourist toys. It’s our culture. It’s a treasure.” New institutions such as the Black Masking Indian Cooperative are designed to help directly support musicians and artists while other ventures will help them gain access to broader markets.

The Chapman family house.

The outsiders attracted by culture also bring income to the artists, performers, restaurants and hoteliers in the area. But that’s not the only outside money that culture can attract. It can also draw new investors and developers whose goals may align with existing residents — or not. DeVan Ecclesiastes has those investors on her mind, too.

Demetrius Chapman, age 60, saved up earnings from her job at a childcare center and bought a house in 1976, three blocks from the elevated Claiborne expressway, which is visible from her front porch. “It’s been the family house ever since I bought it,” she says.

In addition to her late mother, various siblings, cousins, nieces and nephews have stayed here for years at a time. They worked jobs in nearby kitchens, schools and clubs while helping Black Masking Indians sew, helping to run social aid and pleasure clubs and playing in local jazz bands.

Despite their importance to the local culture, no one in the Chapman family has become rich from these jobs. Most work in the low-wage tourist economy.

“Our culture-bearers make the culture we know possible,” DeVan Ecclesiastes said. “But so many of them work in the service industry or the gig economy, which doesn’t offer lots of potential for growth.”

A few years ago, to pay rising tax bills, the Chapman Family fired up their kitchen stove and began selling plate dinners: $10 for a plate loaded with fried fish, stuffed bell peppers, potato salad, green peas, a triangle of white bread and a brownie.

That sort of fundraising became necessary when, all around the Chapmans’ home, the neighborhood began changing rapidly. Since Tremé is bounded by the French Quarter on the side closest to the Mississippi River, Airbnbs have proliferated here. Though Tremé families used to stay in homes for generations, only a smattering of those intergenerational households remain. That makes the Chapmans a rarity.

“Ask anyone here, they’ll tell you, ‘Those people have been there forever,’” says Chapman.

As the neighborhood has gentrified, bringing with it rising property taxes and an increase in speculators, keeping these homes hasn’t been easy for the Chapmans and other longtime residents.

Last year, the Historic District Landmark Commission (HDLC), which oversees the exterior architecture of the city’s historic neighborhoods, issued the Chapmans a “demolition by neglect” citation, which means that a section of the structure has been neglected to the point that the Commission’s staff believes that the entire building could deteriorate if repairs aren’t made. The notice has thrown the Chapman family into a state of worry because it means that they could lose their home.

So far, the HDLC has granted an extension. But the family still frets every day. Once a demolition-by-neglect citation is issued, the Commission can levy daily fines against the property owner. If the fines go unpaid and the work isn’t completed according to HDLC standards, the Commission can hire a contractor to complete the work and place a lien on the house, against the amount of the fines and repairs.

For DeVan Ecclesiastes, keeping families like these in their homes is a critical part of cultural preservation along the Claiborne Corridor. She is working with community partners such as Housing NOLA and with the city’s Department of Code Enforcement to strategize and implement larger fixes. But at this point her approach is also granular: she attends individual hearings and makes phone calls whenever she gets wind of a similar situation.

“It takes the same kind of commitment it takes to sew an Indian suit,” DeVan Ecclesiastes says. “You have to keep your eye on every little bead and be so dogged every day.”

Part of what keeps her going is the stories behind the households that are now struggling. Until Gloria Chapman, Demetrius’ mother, died 10 years ago, she frequently stuck her head out of the back kitchen window. “My mom was a person who thought that every child in the neighborhood was her child,” Chapman says.

When Gloria Chapman was done cooking, she and other family members liked to retire to the house’s front porch, elegantly constructed with beautiful turned columns and a pretty frieze of carved-wood decorations that line the top of the porch.

Today, the porch-sitting tradition continues. Other neighbors tell their children to walk home on a route that passes the Chapmans’ corner, because someone will always be there to watch them. “If we’re not out here on the porch, the door will be open, looking out onto the street,” Demetrius Chapman says.

The orange double-shotgun house with its well-known porch looks out onto Ursulines Avenue. Even beyond the architecture, the porch has become a cultural icon in its own right. For 35 years, it has been the first stop for the Sudan Social Aid and Pleasure Club during the club’s annual parade, in November. Crowds gather outside to hear the brass band and watch club members in colorful outfits dancing up and down the house’s two sets of front steps and onto the broad front porch.

Last year, with great regret, the family told club members that termites had weakened the support beams, putting the porch into disrepair and making it unsafe to dance on. The club still paid respects by making its first stop at the house. But, for safety reasons, the family strung yellow tape between the porch columns to mark it off-limits for second-lining.

In the HDLC citation, the family was ordered to repair a list of violations, all of them porch-related. But working low-wage service jobs doesn’t bring in the money to repair the posts, railings, floorboards and termite-damaged beams with the required craftsmanship and the cypress wood and other historic materials that are mandated to bring the porch to HDLC standards.

The citation notes that an anonymous “citizen” was the source of the complaint. The Chapmans see that person as a vulture of sorts; shortly before they received the citation, they say they saw a local real-estate investor standing on the corner, snapping photos of their home.

“That’s common,” says DeVan Ecclesiastes. “Someone who wants your house can call HDLC or Code Enforcement to complain about you and in short time, your house can end up on the auction list [for city-adjudicated properties].”

Not long after the citation arrived, a realtor left a note on their front door, asking if they were interested in selling. Larry Bruce, 60, who has lived in the house since he married Valerie Chapman in 1992, replied with a note. “I told him that this is a family home and that it is not for sale. We are keeping it for future generations,” Bruce says.

DeVan Ecclesiastes likes to recall a short story about an imaginary town where white folks at first want the land in the mountains, then the beachfront from one generation to another. The black people who live in “The Bottoms” – the undesirable land — first live on the beach but then are forced to the mountains, then back to the beach to make way for the whims of their wealthy white neighbors.

“That’s the story of black neighborhoods in America,” she says. It also alludes to the history of the Claiborne Corridor. “But our next chapter is still being written,” she says. “And this time with a commitment to equity.”

Simba Marvin serves up fresh juice at the VeggieNOLA pop-up stand.

Earlier this year, bridge pillars and girders near the intersection of Orleans Avenue were painted with fresh new murals in anticipation of what’s to come. Just past the paintings, at the point where North Claiborne intersects with the new Lafitte Greenway, a prototype hints at the future. There, a brightly painted shipping container called Veggie Nola is a food stall serving Bissap Breeze fresh juices and packaged snacks on demand along with pre-prepared salads and food, ordered in advance. Veggie Nola is a catering company owned by New Orleans musician and herbalist Tyrone Henry, who also runs Bissap Breeze, a successful hibiscus-tea manufacturing company.

For Henry, who grew up in the area, this fledgling market is part of his dream. Soon, he said, his shipping container will be joined by other neighborhood entrepreneurs including his colleague, Gary Netter, who will work with other retailers to create “Backatown Plaza.”

Beyond the healthy food he sells, through his business, Next To Eat, Netter is able to provide technical assistance and commissary-kitchen services to other culinary businesses in the plaza, once electricity and plumbing infrastructure are added to the site.

That would mean that Henry could also sell prepared food from his catering company, also called Veggie Nola.

Henry said he’s particularly encouraged by conversations he’s had with his customers, who range from people who have never left the city to those who have traveled the world. “The way I see it, it is a learning tree. And the tree I’m talking about is the community. It’s like a tree, even though it’s underneath the bridge,” Henry said.

Smallwood believes the orange shipping container is a small harbinger of the larger successes to come. “You can’t undo what’s done. They’re not going to replant the trees,” she says. “My position is that we should make the best of the talents that are already there. We should be asking residents, ‘What are your dreams? Can those be put into place?’”

EDITOR’S NOTE: We have corrected the photo caption that misidentified the person serving juice at the VeggieNOLA pop-up stand. His name is Simba Marvin, not Shaka Zulu.

This article is part of “For Whom, By Whom”, a series of articles about how creative placemaking can expand opportunities for low-income people living in disinvested communities. This series is generously underwritten by the Kresge Foundation.

Katy Reckdahl is a New Orleans-based news reporter who is a frequent contributor to the New Orleans Advocate and the Hechinger Report and has written for The Times-Picayune, The New York Times, The Daily Beast, The Weather Channel, The Nation, Next City, and the Christian Science Monitor.

Jamell Tate is a photographer born and raised in New Orleans. He loves his city and its many beautiful, wonderful and ugly moments, and documents those moments by freezing them in time.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine