When Eric Gonzaba was growing up in rural Indiana, he says that everything he learned about queer history had happened “in far-off places.” Little did he know that a mere 25 miles away in Louisville, Kentucky, an unassuming brick building on East Main Street had hosted one of the region’s first gay discos, which opened in 1973 and was known for its dazzling drag shows.

Now, as a trained historian and professor of American Studies at California State University, Fullerton (CSUF), Gonzaba is uncovering and preserving hidden histories like this one through a digital project called “Mapping the Gay Guides.” The project, which is co-led by Amanda Regan, a lecturer in the Department of History and Geography at Clemson University, uses a series of travel guides published by Bob Damron to map historic queer spaces across the United States.

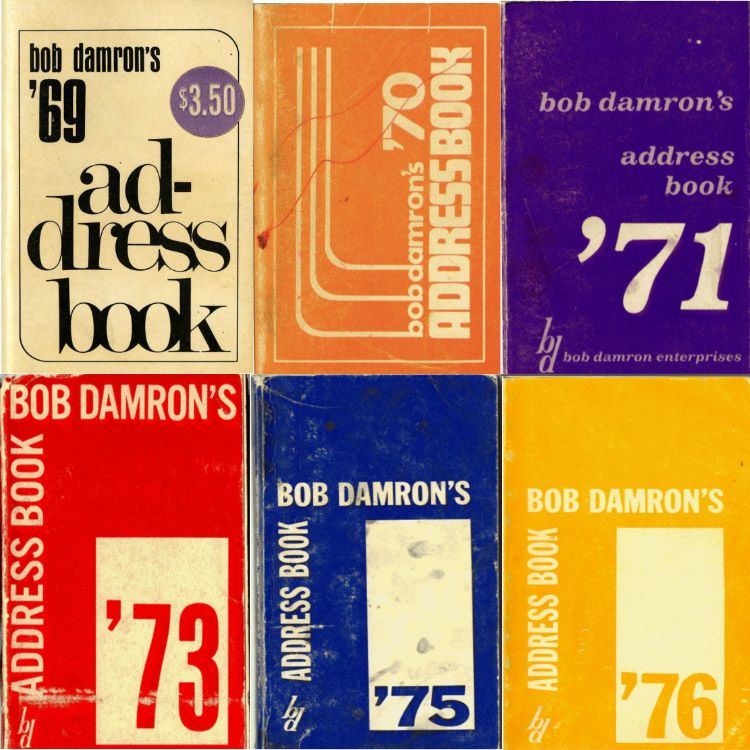

Damron was a traveling businessman who took note of the gay or at least gay-friendly bars, bathhouses, theaters, bookstores, restaurants, and shops he discovered on his many trips. He then published a series of travel guides based on that research beginning in 1965. His collections, originally known as the “Address Book,” became a survival guide for queer road trippers, comparable to the Jim Crow-era Negro Motorist Green Book, which guided Black travelers through the country.

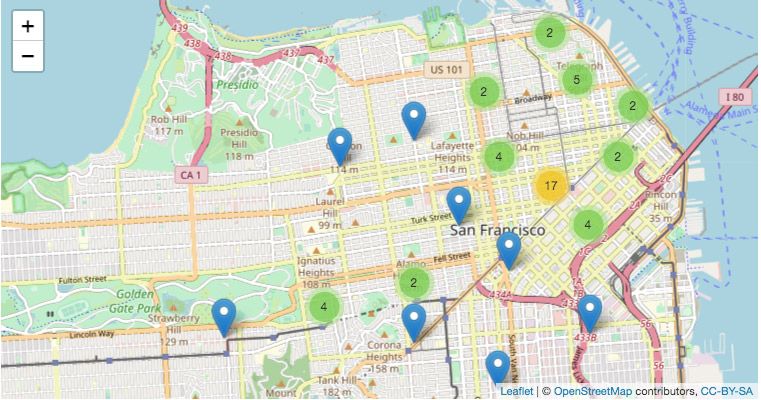

Mapping the Gay Guides’ website hosts an interactive map, where the hangouts from Damron’s books are transformed into little blue pins. Click on the pins, and you can explore the features of Damron’s favorite haunts as they were described in his original writing.

(Screenshot via Mapping the Gay Guides)

Users can watch locations appear and disappear by clicking through the map from year to year: The number of sites listed in the Pacific Northwest more than triples between 1965 and 1972. Meanwhile, one of the popular sites from early-1970s New Orleans, the Upstairs Lounge, disappears from the map in 1975.

Another section of the site hosts short histories of some of the sites on the map, written by Gonzaba and CSUF graduate students. Here, users can learn the heartbreaking reason behind the disappearance of the Upstairs Lounge: On the evening of June 24, 1973, an arsonist set fire to the building while dozens of patrons were gathered inside enjoying Sunday drink specials. Thirty-two people died as a result of the fire. The attack was the deadliest known attack on a gay club until the 2016 Pulse shooting in Orlando, Florida.

There are cheerier histories, too, like that of the Paramount Steak House in Washington D.C. The popular restaurant opened in 1948 and began catering to the gay community sometime in the 1950s. Unlike most sites listed in Damron’s old address books, this one is still around today. More than seventy years after it opened, the establishment is now a landmark along Washington D.C.’s annual pride parade route — an homage to its longstanding place in Washington D.C.’s queer culture.

Since its launch in February 2020, Mapping the Gay Guides has dropped hundreds of pins on its interactive map across all 50 states, Washington D.C., Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands (Damron did not distinguish between entries in the U.S. Virgin Islands and the British Virgin Islands, so neither does Mapping the Gay Guides) from the 1965 to 1980 address books. The project received a $350,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) in April 2021, which will allow it to spend the next three years digitizing, transcribing, and geolocating data from the 1981 to 2000 guides.

“We want our project to be a launching off point for researchers and public historians to think about how queer people have literally and figuratively been on the map for decades,” says Gonzaba. Mapping Damron’s address books means making their contents more available to researchers than ever before.

The project was also a response to what Gonzaba calls “a fairly depressing moment in queer communities across the country dealing with the collapse of LGBTQ spaces.” The COVID-19 pandemic hit queer businesses hard. Famous spaces like Stonewall, Julius Bar, and Henrietta Hudson, all in New York City, made headlines when they were forced to appeal to patrons for support via crowdfunding campaigns to stay afloat during coronavirus shutdowns.

But even before the pandemic struck, queer spaces were on the decline. Research from Greggor Mattson, professor of sociology at Oberlin College, shows that the number of queer bars and nightclubs in the United States declined by 36.6% between 2007 and 2019. For his research, Mattson also relied on Damron’s address books, which were published annually by San Francisco-based Damron Company until 2019. Digital projects like Mapping the Gay Guides are well-suited to archiving the histories of spaces like these so that even as they may close, their stories won’t be lost to time.

The “address books” (via Mapping the Gay Guides)

New technologies also have the power to make hidden histories more accessible and give people who have traditionally been excluded from the academy opportunities to participate in the preservation of their histories in new and lasting ways. “The creation of digital tools, more affordable tech such as sophisticated smartphones, and easy-to-use interfaces on our devices and platforms has … given agency to people and from that stems a growth in digital humanities projects,” says Megan Smith, professor of creative technologies at the University of British Columbia.

Still, these new technologies are not free of ethical questions. Gonzaba and Regan grapple with concern that making knowledge of hidden queer spaces available on the web could make those spaces or their patrons targets of abuse. However, many of the sites that Damron cataloged decades ago are no longer in operation or their uses have shifted over time, reducing this risk.

The pair also emphasizes that the travel guides they use as primary sources for Mapping the Gay Guides were authored by a gay, white man from the relatively progressive city of San Francisco. Reading them with a critical eye reveals implicit biases, like the fact that Damron labeled most southern sites and sites popular among the Black community as less reputable than others. Contextualizing Damron’s writing and exploring its biases is vital to Mapping the Gay Guides’ work.

Rebecca Caines, who studies digital and site-specific art at the University of Regina in Saskatchewan, Canada, also says that effort must be made to ensure that new digital projects will last over time. That means they can’t rely on high-level technical support or expensive equipment that will only be available to a community for a limited time. “This is a feature of new media work in general,” she says, “But it needs to be carefully considered when marginalized people are sharing their stories and experiences.”

Regan describes the threat of technological obsolescence as “one of the greatest hurdles” to doing digital work. She and Gonzaba document their methodology and save copies of their data in sustainable formats to ensure Mapping the Gay Guides will be replicable, even if the technology that powers its current interactive map ceases to work. With some of the new NEH funds, the team also plans to deposit copies of the project in a university library’s archival repository and transition its map into JavaScript, making it more accessible and sustainable.

Mapping the Gay Guides exemplifies the many colorful possibilities of a digital history project handled with appropriate care. Like other creative digital projects, it can give users a fresh perspective on their cities and, according to Caines, “offer new ways to hold onto histories, reclaim identities, provide new forms of communication between generations, and allow for new forms of activism and organizing.”

This article is part of “For Whom, By Whom,” a series of articles about how creative placemaking can expand opportunities for low-income people living in disinvested communities. This series is generously underwritten by the Kresge Foundation.

_920_518_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)