Clay Banks/Unsplash

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

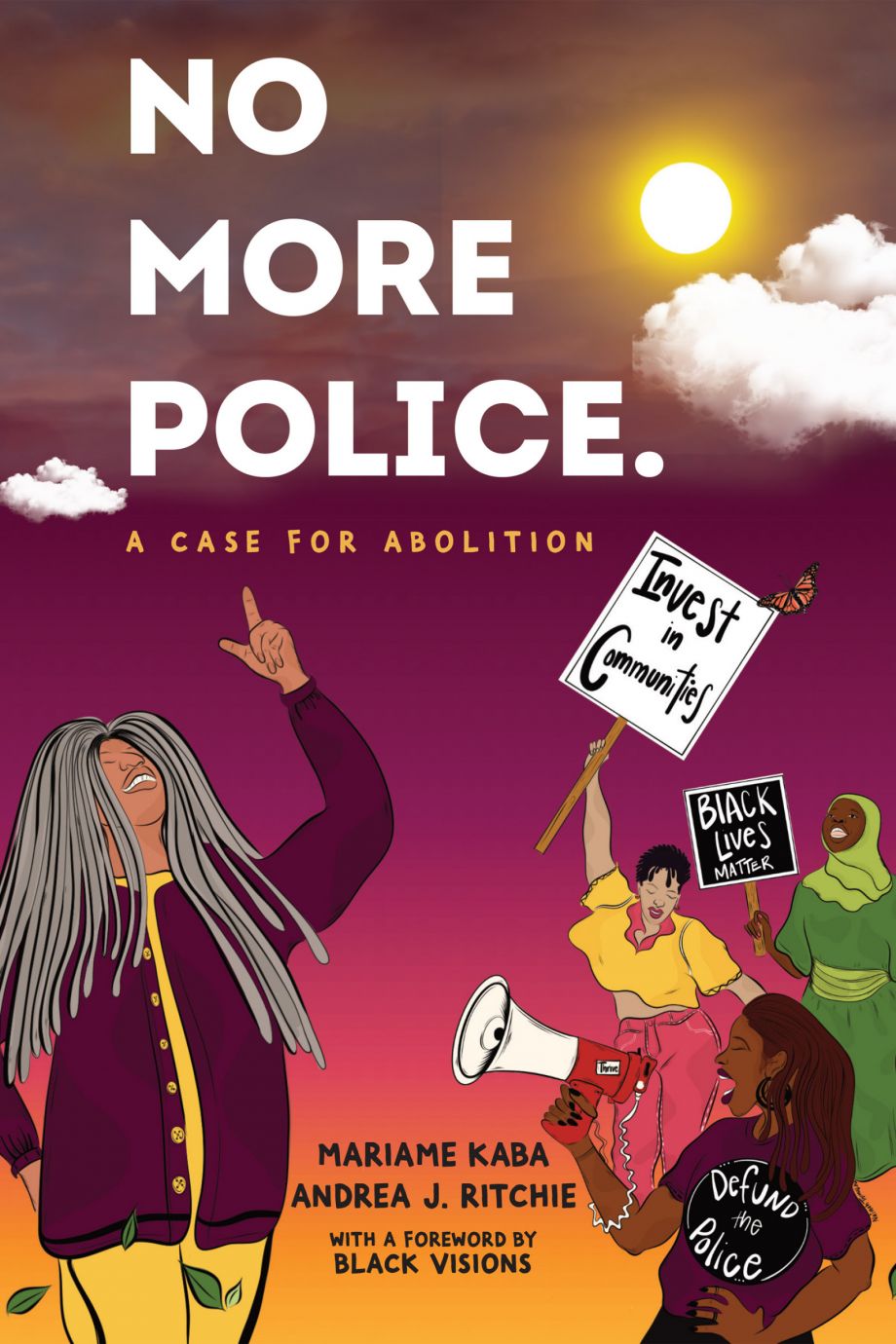

Become A MemberThe following is an edited excerpt from the book “No More Police: A Case for Abolition,” by longtime community organizers and abolitionists Mariame Kaba and Andrea J. Ritchie, published by The New Press. In it, the authors issue a call for building safe, flourishing communities through local experimentation, using tools ranging from participatory budgeting to street fridges.

There is no cookie-cutter, one-size-fits-all solution to the multiplicity of needs, conflicts and harms that exist in our individual communities that can immediately be replicated across the country and scaled up to a national level. That is what police falsely claim to be. As Chicago organizer Damon Williams succinctly puts it, “When I see police, I see one hundred other jobs smashed into one thing with a gun.”

Safety is — and likely will always be — a work in progress. We need to build toward safer communities based on solid foundations through experimentation and practice, rather than being rushed into recreating safety on the carceral state’s terms. Over time, we can stitch our experiments together into an infrastructure of community safety at a scale that can meet our needs. Collectively, we must be willing to commit to a spirit of experimentation, build our capacity to try things, embrace failure and commit to multiple cycles of “practice, fail, learn, repeat.”

That is the principle behind the MillionExperiments.com website and podcast that our initiative Interrupting Criminalization launched with Project NIA in 2021. They highlight multiple ways people are practicing creating greater safety in their own communities. That includes mutual aid projects, community gardens, street fridges, violence prevention and interruption initiatives, community crisis-response models, barbershop conversations and hotlines for people concerned they might harm someone else.

(Courtesy The New Press)

As Ruth Wilson Gilmore reminds us, abolition is a process of repeated rehearsal toward a new future. Rehearsals are just that — practice, not perfection, “abolition unfolding.”

A key component of creating greater safety is challenging the visions of safety we have been fed by the carceral state, and experiencing greater safety through relationships and community. We can start by asking ourselves and each other what safety and freedom look and feel like in our lives — as both of us regularly do in workshops, study guides and art projects like the Abolition Imagination and COVID safety postcard series.

Art can make us think and feel differently, and to ask ourselves “Why can’t we do it this way?” “Why don’t we try this?” and “Why is that not possible?” We can also ask ourselves these questions in conversation—as abolitionist organizer Benji Hart describes in the “Practicing Abolition, Creating Community,” zine. The African American Roundtable created a zine about what safer communities might look like that offers another example of what such an invitation to dream different futures can yield. Black Visions in Minneapolis has created self-reflection and community conversation guides that can serve as tools to help you start where you are.

Collective imagination exercises can also take the form of community-based surveys and participatory research projects. During the 2016 youth-led campaign to prevent the construction of a $95 million police training facility in a Chicago neighborhood where dozens of schools and clinics were shuttered in a classic case of organized abandonment, #NoCopAcademy organizers surveyed residents to find out how they would spend the money instead to build greater safety. They collected over 1,000 community recommendations for investments in public health and safety on the city’s West Side. None involved construction of a new police training facility. Almost half focused on increased spending on schools and youth programs.

In 2017, partners in the Liberate MKE campaign in Milwaukee surveyed over 1,000 people about what would create conditions for greater safety. Residents responded by calling for investments in housing, youth employment and violence interruption. In Phoenix, Poder in Action summarized the results of surveys of 10,000 Phoenix residents conducted in 2018 and 2019 in “Phoenix Futuro.” Over 1,300 Philadelphia residents’ responses to similar questions were summarized by the Movement Alliance Project in “Safety We Can Feel.” And, in the summer of 2021, the Nashville People’s Budget Coalition surveyed over 5,000 residents about their budget priorities as policymakers tried to cite crime rates as a reason to increase, rather than decrease, police funding.

Across the board, the majority of respondents in each of these communities called for investments in public schools, affordable housing, social services and violence interrupters, rather than in police. Community surveys can serve as an important starting point for conversations around what greater safety looks like, and what it would take to create it in communities.

Notably, even city-sponsored surveys point us in similar directions—almost 90% of 38,000 residents surveyed in Chicago in the summer of 2020 supported divestment from police and investment in community programs. Even where surveys claim low public support for the demands of defund campaigns, the majority of residents support their underlying premise when asked about increased investment in housing, jobs, education and health care and decreased investment in policing and punishment.

When we’re reimagining public safety, it is critical to engage and center people who have both experienced and engaged in harm. The National Council of Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls is engaged in a participatory research project with its members as part of its Reimagining Communities campaign. Participants are exploring questions around what would have prevented the harm they experienced and engaged in and what accountability and healing could look like. Based on these conversations, they are imagining and organizing toward the relationships, programs and institutional responses that would create greater safety for everyone in their communities.

Community events and People’s Assemblies can serve as locations where safety dreams can be developed. In 2020, the Jackson, Mississippi, People’s Assembly — created when former Mayor Chokwe Lumumba was elected to provide a direct mechanism for community accountability and governance — debated what would be possible if police department funds were reinvested in community programs. The Black Nashville Assembly is similarly engaging residents in debates around their visions for safer communities. And, in Minneapolis, a coalition of Minneapolis organizers led by Black Visions held People’s Movement Assemblies across the city in 2021 to build a vision of a safer, more just city.

Groups across the country are also using participatory budgeting to gain more direct control over where school, local and federal funds are spent, and drive investments to meet material needs and community-based safety strategies. In the midst of the 2020 uprisings, Decriminalize Seattle was successful in redirecting $30 million from the police to a participatory budgeting process that will take place in 2022. The process will be guided by the Black Brilliance Report, a 1,200-page document summarizing the results of a Black-led research project focused on what will create greater safety in the city. The Black Brilliance Project involved over 100 researchers, including youth, elders, people with experience in the criminal legal system and “others who have been invited — many for the first time — to engage as researchers in their own communities and lives.”

Together they worked to answer the following questions based on their lived experiences: What creates true community safety? What creates true community health? What do you need to thrive? This Black-community research project brought thousands of voices across all ethnic and racial backgrounds into the process of envisioning safety, health and thriving communities. The results focused on five priority investment areas which will serve as “buckets” for the participatory budgeting process: housing and physical spaces, mental health, youth and children, economic development, and crisis and wellness.

Under a transformative justice framework, we are all called to labor. All of us can make offerings. We need thousands of tools, not one. We’re all collectively responsible for making safer communities. No one person is responsible for coming up with the answers; no one person is responsible for the mess we’re in. We’re all complicit — it’s just a matter of degree. In other words: we all have a part to play in transforming our conditions and ourselves.

We must practice accountability with those we love, work to uproot all forms of oppression, organize across difference and build power to challenge the carceral state. It will take all of us to dismantle death-making institutions, change the ways we understand and relate to each other, and build safer and more just communities without them.

We’re already doing it. We’re dismantling, changing and building all the time, and we can practice wherever we are.

Copyright © 2022 by Mariame Kaba and Andrea J. Richie. This excerpt is adapted from “No More Police: A Case for Abolition,” published by The New Press. Available in simultaneous hardcover and trade paperback. Reprinted here with permission.

Mariame Kaba is a leading prison and police abolitionist. She is the founder and director of Project NIA and the co-founder of Interrupting Criminalization. She is the author of the New York Times bestselling “We Do This ’Til We Free Us,” co-author of “No More Police” and lives in New York City.

Andrea J. Ritchie is a nationally recognized expert on policing and criminalization, and supports organizers across the country working to build safer communities. She is co-founder of Interrupting Criminalization, the author of “Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color” and co-author of “No More Police.” She lives in Detroit.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine