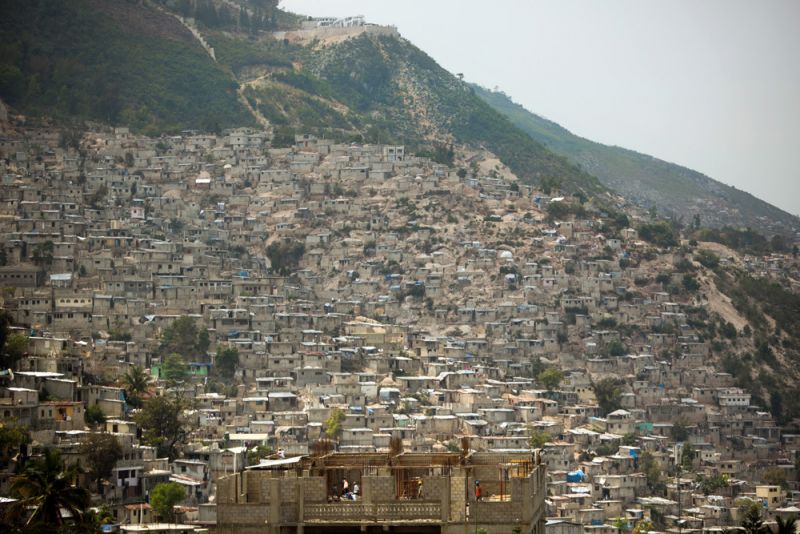

Seven neighborhoods cling to the side of Morne L’Hôpital, a steep hill that rises above one of the most exclusive suburbs of Port-au-Prince, Haiti. It was my longtime motorcycle chauffer, Francois, who first took me up here to show off his new land.

Like a chorus of church bells, the sound of mallets striking rebar filled the air. Once, this meant that residents were digging out valuable metal for resale. Now, it means construction — a lot of which has been happening on Morne L’Hôpital lately, as two-thirds of this otherwise green hill of scrubby brush has been covered over with cinder block.

Nicolas Coras, 37, lives in the Menard neighborhood, two ravines over from Francois. He explained how to settle here: Find someone to sell you a land title, build a home and start paying taxes. Simple. Six years ago he paid $560 in U.S. dollars for his plot, where he has been steadily adding to the home that he shares with his wife and two little girls. “The earthquake barely touched us here,” he said.

Furthermore, there is a loophole. “As long as your house is still under construction,” said Jenny Francois, Coras’ neighbor and of no relation to my chauffeur, “you don’t have to pay taxes.” She and eight of her family members, who moved from a neighborhood near the Port-au-Prince airport two years ago, now live in the one completed room of what is to be a four-room home with a generous yard. Walls of the second room are up, with openings left for window frames and a tarp as a temporary roof.

While many residents on Morne L’Hôpital relocated because of the 2010 Haiti earthquake, many more, like Coras and Jenny Francois, did not come to the mountain fleeing damaged homes. They had simply been renters from various parts of Port-au-Prince looking to upgrade. According to officials, people with similar dreams began settling on this slope as far back as 50 years ago.

Given the notoriously archaic and much-maligned Haitian land tenure system, which stalls development in much of the region, here is a well-oiled process allowing residents to seemingly claim property for the average cost of a year’s rent in the more established Port-au-Prince neighborhoods.

This is urban growth, Haitian style, as necessity has forced it to evolve. It now continues in the vacuum of unsuccessful development schemes and the wake of post-quake spiked rents. The only problem: It’s based on a fiction.

Gallery: Morne L’Hôpital, Haiti

All photos © Allison Shelley

“It’s illegal,” says Dr. Jean-François Thomas, Haiti’s new Minister of the Environment. “The land is all owned by the government.”

In fact Morne L’Hôpital is under special environmental protection, covered by a 1963 law and a decree issued in 1986. And the government has finally sounded the alarm.

“Morne L’Hôpital had been a highly important zone in terms of water absorption,” Thomas said. “This country is mountains. Everything goes from up to down here. Now with the hill covered in concrete, rain continues down in a big flood, all the way through Port-au-Prince. There are landslides all of the time.” He describes the situation as catastrophic.

Thomas said that the pace of settlement has ramped up in the past 20 years. Le Matin, a local daily paper, reports the population of Morne l’Hôpital at 246,000, with more than 50,000 homes extending from affluent Petionville to quake epicenter Carrefour.

Former Deputy Chief Minister of the Environment Pierre André Gedeon called the building “anarchic.” Last June, his ministry marked over 400 houses that lay in the floodplain for demolition, sparking angry protests and teargas — which stopped the plan in its tracks.

Thomas, appointed in January and the third official to hold his post in less than a year, has a different attitude. “We waited too long,” he admitted during a recent site visit, surrounded by heavy security. “Many of the people have lived here a long time and, we know, have no way out. We can’t punish them by kicking them out because we did not react before now.”

His plan focuses on making the most of the remaining virgin land. Dubbed Ann Sove Lavi nan Mòn Lopital — or “Let’s Save Lives on Morne l’Hopital” — it aims to preserve a 500-hectare (1,235-acre) “green gate” buffer around the existing homes and to stabilize the ravine using concrete tanks: One to filter out rocks and sand, the other to retain water to slow the flow during heavy rain.

Thomas touted the program as a job creator, with local residents to be hired as part of a 1,000-member team for the seven-month reforestation work. His initiative also includes putting an immediate halt to new development.

Like many other ambitious, well-intentioned programs in Haiti doomed by frequent cabinet turnovers and a lack of funding, Thomas’ may never come to fruition. But while curtailing construction might fix several of the city’s glaring problems, it exacerbates another: Access to land and affordable housing.

Meanwhile, Coras is stuck. Before the earthquake he moved neighborhoods every several years. But while the disaster did not destroy his home, it did do away with his job at the municipal water sanitation plant. Now, like many others, he scrapes together work here and there. But with no rent to pay he has no incentive to leave.

Francois, for his part, said he couldn’t wait to move his family in. He walked me across a well-laid foundation marking where interior walls will go up. Here, the entry hall, there, a room for his baby girl — all her own. He explained how the roof will be corrugated and catch water during the rains for household use. And then he pointed toward the horizon.

“Just look,” he said. “You can see all the way to the sea.”

Allison Shelley is an independent documentary photographer. She is a former staff photographer for the Washington Times, director of photography for Education Week newspaper, and is now co-director of the 250-member non-profit Women Photojournalists of Washington. She is currently working on a long term multi-platform project focusing on teenage maternal mortality worldwide.