This story was published in collaboration with YR Media (formerly Youth Radio) as part of the Equitable Cities Reporting Hub for Environmental Justice, an initiative led by Grist and Next City.

Oscar Sanchez grew up in an immigrant family on Chicago’s Southeast Side. Everyone in the neighborhood knew someone living with the impacts of industrial pollution and environmental racism. Being low-income was a shared experience in a community where food pantries and thrift stores are considered essential services.

When you talk to Sanchez, you notice how often he uses the word “love.” The 25-year-old says he “constantly tries to show love and grace because I feel that we’re conditioned not to give that.” He loves people, and he loves the Southeast Side. Walk around the neighborhood with him, and he says hi to everyone. A lot of people know him by name, and if they don’t, he’ll introduce himself.

It’s that love of people and community that led Sanchez to activism. He wants everyone to treat his neighbors as well as he does. “Just because we are poor, we should not be treated poorly,” he says. His work started as a teenager in anti-violence and restorative justice, but he gained national acclaim two years ago for a hunger strike against efforts to move a scrapyard into the neighborhood. The move could have had devastating health and environmental impacts, and exacerbated more than a century of racist zoning practices that have disadvantaged the neighborhood. “We literally had to put our lives on the line,” Sanchez says. The strikers won.

Sanchez believes his experiences can translate to city politics in the future, where he wants to speak for those who might otherwise go unheard. The tight-knit community he loves so passionately drives him to push for better, whether it’s campaigning for a seat at the table or opposing harmful industries.

“How can I say, ‘I love you,’” he says, “but not fight for you?”

After a quick stop home to bundle up, Oscar Sanchez sets back out to collect names of supporters for his city council campaign in December 2022. (Photo by Miranda Zanca for YR Media and CatchLight Local)

Sanchez was involved with his community from an early age through his family’s work at a neighborhood church, where he helped with fundraisers. He cofounded the Southeast Youth Alliance in 2018, an organization that engaged young people in improving the neighborhood. Then he joined the Alliance of the Southeast, a community organizing group for the Southeast Side, where he worked with residents to understand and participate in zoning and land-use decisions impacting the community.

That’s how Sanchez found himself at the center of a fight against a metal recycling facility the city hoped to relocate to his neighborhood. The struggle started in 2019 when General Iron applied to move a scrapyard from the affluent neighborhood of Lincoln Park to the Southeast Side.

The plan did not surprise Sanchez, nor did its all-too-familiar message to the neighborhood, which is predominantly Latino, with a lot of working class residents. “It’s been a pattern and historical demonstration of how we’re viewed as a dumping site,” he says.

As in many cities nationwide, factories, steel mills, and the like have been strategically placed in neighborhoods populated by people of color since industrialization came to Chicago in the 1860s. Starting in 2004, the city designated 26 neighborhoods, including the Southeast Side, as “industrial corridors” — areas zoned for industrial or manufacturing activities. Those are areas with high populations of Black and brown people, Sanchez notes: “They were turned into industrial corridors because it was cheap land to be purchased.”

For residents living around these sites, the health impacts are real. The Southeast Side endures high levels of pollution, including fine particulate matter, airborne toxins, and proximity to hazardous waste — all of which lead to higher cancer risk and respiratory hazards. Sanchez says he could not watch the city move a metal recycler into his community and exacerbate these issues, so he helped coordinate opposition through the Alliance of the Southeast and other community organizations. “We did marches, we did community teach-ins,” he says. “We attended community town halls.”

Opponents of the move also filed a civil rights complaint and called for multiple health impact studies. Still, the Illinois EPA approved permits for the move in June 2020. The Chicago Department of Health approved the first of two city permits that fall.

As the fight dragged into its second year, Sanchez spoke to experienced activists about what options remained, and decided to take an extreme measure. He and a few others launched a monthlong hunger strike in February 2021. Many people joined at different points, including a city council member. “It was such a hard decision to make,” Sanchez says, and one that has left long-term consequences for his physical and mental health. “That experience — and this is what I always tell folks … we should not be doing this again.”

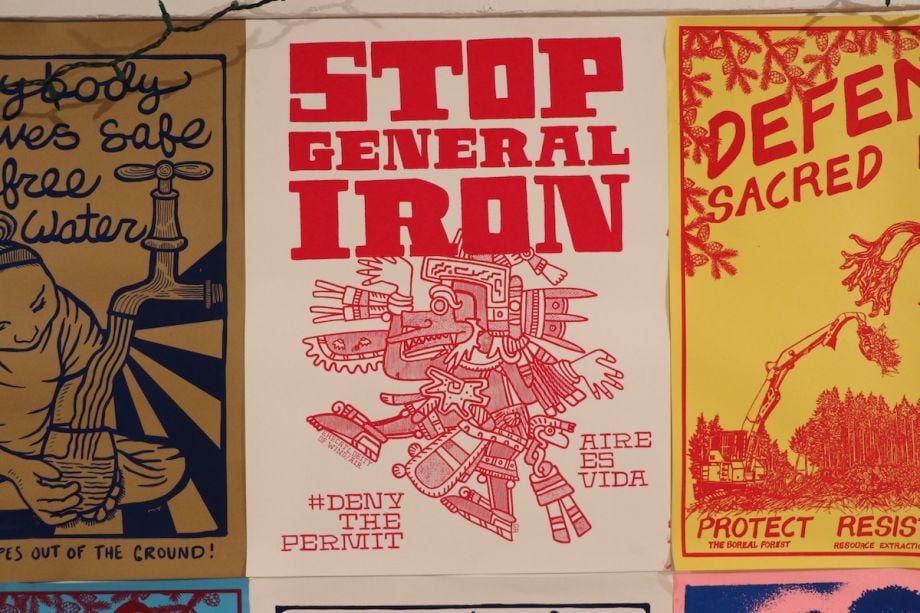

A poster protesting the proposed move of a metal recycling plant (General Iron) to the Southeast Side and the environmental impacts, with a Spanish phrase meaning “air is life.” (Photo by Miranda Zanca for YR Media and CatchLight Local)

Soon after the hunger strike, the EPA requested a health-impact assessment of the facility. It was a turning point, and in early 2022, the city denied the permit, barring General Iron from moving to the Southeast Side. The company is currently appealing that decision, but for Sanchez and other residents it was a validating victory. “When the people fight, the people win,” he says. “Because if we’re not the ones deciding our future, then that’s being decided for us.”

But Sanchez still grapples with the idea that success came at the expense of his health. He feels compromised physically, believes it shouldn’t have had to happen, and laments the pressure it put on family and friends who worried about his safety. “But the thing is, we literally had to put our life on the line. So we have to sacrifice our life in order to receive life.”

After years of fighting the city as an activist, Sanchez had hoped to help lead it as a politician. Recently, he ran for alderman, which is what Chicago calls its city council members, of the 10th Ward that includes his Southeast Side neighborhood. Although his bid was unsuccessful, Sanchez still believes in fostering a change in which “local officials truly understand how to create systems of care for us to be self-sustaining in a manner that we can create an economy that’s not exploitative.”

He draws inspiration and motivation from the vibrance of the community that he loves. On a Sunday afternoon last fall, Sanchez recalls feeling that love: “I saw children playing in a playground. I saw some youth riding their bikes. I was hearing a Mexican band. You just see life. You see this joy and you remind yourself, this is what we do this for.”

Last October, campaign supporters gathered in Sanchez’s living room on a chilly Sunday before heading out for an afternoon of door knocking. The volunteers chattered as neighbors trickled in. Sanchez told everyone to help themselves to coffee, pan dulce, and water bottles, and to make themselves at home. “Mi casa es su casa,” he told them, raising his voice over the din of several conversations.

In some ways, Sanchez says, running for office put him in a very different position than being a community organizer. “Say, ‘I’m a community organizer,’ and people open up,” he explains. “Say, ‘I’m running for city council,’ [and] people are like, ‘Oh, you’re a politician. I don’t trust you.’ So building trust is very different.” Since losing the race for alderman in February, Sanchez isn’t sure what’s next. But he’s still building a base of supporters, and will run again if he feels called to action.

Despite everything he poured into his campaign, Sanchez had never planned on being a career politician — he knows there are other opportunities to make a difference. He wants to focus on elevating others in the community and fostering fundamental change. “We’re not doing this for Oscar Sanchez,” he says. “We’re doing this to continue building this movement of having a safe, thriving community.”

The photographs for the project were created through a collaboration between YR Media reporters and CatchLight Local, a new collaborative model for visual journalism that is advancing trust and representation in local media.

Miranda Zanca is a college student at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.