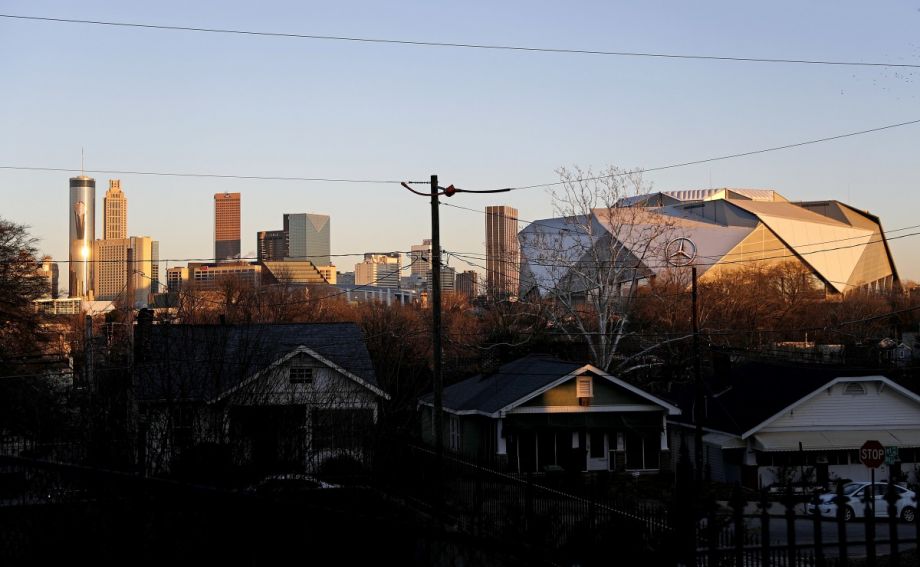

From a distance, the massive Mercedes-Benz Stadium, as of last year the new home of the National Football League’s Atlanta Falcons, is every bit the $1.6 billion spectacle it was meant to be. An eye-catching geometric design, by HOK, with roof panels that slide open and closed like a camera aperture. It’s North America’s first LEED-platinum professional sports stadium.

But the closer you get to the stadium, the more apparent are the same tensions that seem to plague spectacle-driven development everywhere, especially when it’s in such close proximity to areas that have survived generations of redlining and disinvestment, like the Westside of Atlanta, right outside the stadium’s doors.

In the Westside neighborhoods of English Avenue, Vine City, Atlanta University Center and Ashview Heights, only eight percent of households own their homes — a direct legacy and continued symptom of redlining. Meanwhile, an estimated 18 percent of parcels in these neighborhoods are already investor-owned.

“These communities are at risk of being ignored and having no resources invested in them, or worse becoming gentrified so fast the people who are legacy residents here cannot continue to live in the communities where they were raised,” says Anna Foote, Southeast Regional Director for the National Federation of Community Development Credit Unions.

Recent reports from the Brookings Institution and Georgia Institute of Technology tell the tale of rising rents and a yawning income gap threatening to displace Atlanta’s lower-income residents from the benefits promised by the wave of investment coming into the city, from the spectacle of Mercedes-Benz Stadium to that of the Atlanta BeltLine, slowly making its way into the western half of the city.

Foote serves as part of an all-hands-on-deck coalition of local nonprofits, community organizations, philanthropic groups, and not one, not two, not three, but four Atlanta-area credit unions working to prevent displacement of residents on Atlanta’s Westside through the On the Rise Financial Center. The initiative launched in April 2017, with funding and support from partners like Equifax, the family foundation of Atlanta Falcons owner Arthur M. Blank, and Invest Atlanta, the city’s official economic development authority.

“When there’s an opportunity to help support a community that’s going to be impacted by a substantial economic development in the city, some benefits should come into that community, and this is an example of that happening here,” Foote says.

Increasing homeownership among Westside residents is a goal of the initiative, but it starts with something more basic and necessary in an area that has long been either ignored or preyed-upon by most other financial institutions — relationship-building.

“Our first year has been focused on getting the word out about what the center is and what we can do to help people advance in their financial lives,” says Ann Solomon, Director of Strategic Initiatives for the National Federation of Community Development Credit Unions.

Solomon says On the Rise has trained 12 counselors on the Pathways to Financial Empowerment curriculum, who in turn have advised over 200 residents. Solomon expects the Center’s reach to grow year over year, as On the Rise works to build a shared services center that will house credit unions, financial counselors, and On the Rise staff.

“We have ambitious goals because we’re coming into a community with a lot of need. There are over 10 alternative financial service providers [on the Westside], and just two mainstream financial institutions in the community. The ratio is imbalanced, and the kinds of services that people are accessing just drain money from people’s pockets,” says Solomon.

Experts like University of Georgia Law professor Mehrsa Baradaran explain just how debilitating fees from alternative financial service providers can be. In How the Other Half Banks, recently re-released in paperback, Baradaran estimates that using alternative financial services can eat up to 10 percent of a household’s monthly income. “For these families, the total price of simple financial services each month is more than they spend on food,” she writes. And, over the course of a career, The Brookings Institution calculates that check cashing fees can total over $40,000.

Anna Foote, local co-director of On the Rise, underscores the challenge, characterizing the Westside of Atlanta as “a financial resources desert.”

“The banks have disinvested themselves,” Foote says. “There’s a preponderance of check cashing services and pawn shops — places where it costs a lot to cash a check.”

For residents on the Westside, where the poverty rate is 43 percent and the median household income is $24,778, every dollar counts.

Sharon R. Odom, the CEO of 1st Choice Credit Union says that as gentrification continues, initiatives like On the Rise are critical to the Westside’s sustainability.

“A lot of the people that we see are in need of financial education and they are looking for solutions,” Odom says. “Having the On the Rise Center where all of this information is easily accessible to them is huge.”

Odom says that moving forward, building the shared service center that will house 1st Choice Credit Union and financial education programming will be integral to securing the community’s financial success.

“We want to be able to equip people not just with the information, but access to quality services right in their own community,” she says. “That’s the future.”

Aaron Ross Coleman is a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow for 2018-2019. A freelance writer from Atlanta, Aaron’s writing focuses on the intersection of economics and racial inequality. Based in New York, he is a Marjorie Deane Fellow at New York University’s Graduate School of Journalism. Aaron has his B.A. in Political Science from Fort Valley State University. His work has appeared in CNBC, Rewire News, The Huffington Post, and other publications.