On July 9, a coalition of organizations including Mijente, The American Indian Movement of Ohio, Earth First!, and the Columbus Sanctuary Collective blockaded the ICE field office in Columbus, Ohio.

Appalachia Resist

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

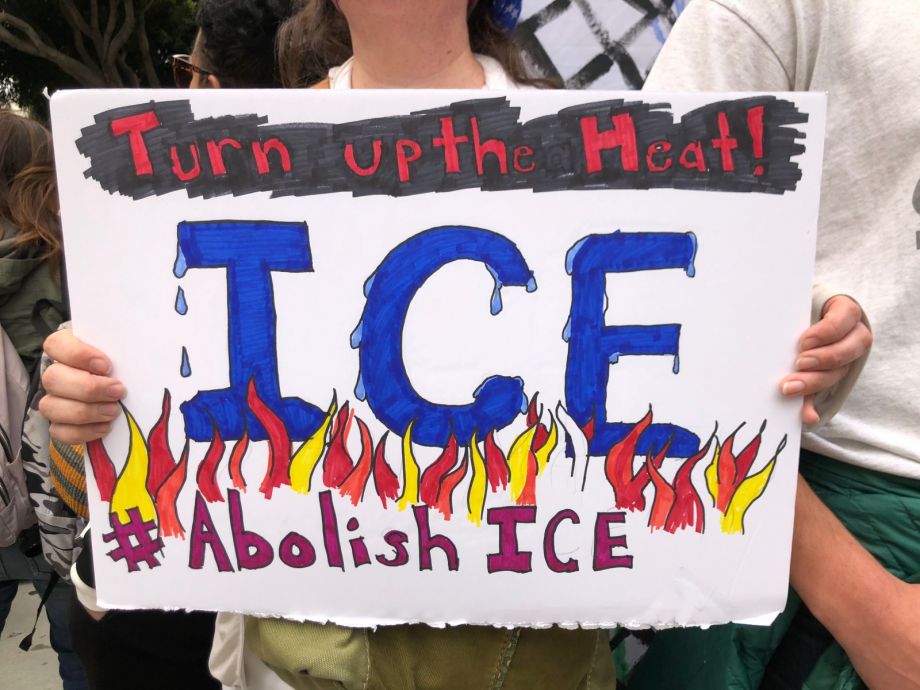

Become A Member“Apply Heat, Melt ICE,” reads one sign popping up at marches and protest encampments across the country.

“ICE is rounding people up in a sanctuary city. ICE get out,” says a banner at the camp outside Philadelphia’s city hall.

All over the internet, and increasingly in the speeches of politicians, from Democratic Socialist Congressional candidate Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to Democratic Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, there’s the growing chorus: #AbolishICE, #AbolishICE, #AbolishICE.

Proponents disagree about how to make that call a reality. And immigrant rights organizers admit they’re scrambling to catch up with the momentum of a position that, until recently, seemed like a fringe viewpoint. But activists mean what they say — they want the 15-year-old agency scrapped. They’re unwilling to wait for mythical “comprehensive immigration reform,” nor will they settle for a return to more relaxed pre-2003 immigration enforcement.

But to abolish a federal agency is no small task, and the likelihood that it would it happen as a top-down decision from the Trump administration is virtually nil. Meanwhile, most families separated at the border remain separated — some, perhaps, permanently — and deportations continue apace, at workplaces, courthouses and private homes.

So all around the country, immigrants and their allies have localized what may seem a daunting national fight. They hunt for political and economic levers that would be more susceptible to public pressure than a federal government who has shown itself increasingly hostile to migrant rights.

It’s not just the encampments popping up outside of ICE and politicians’ offices around the country. Those encampments serve a purpose, but the protests are powered by tangible policy demands.

In Philadelphia, the encampment outside City Hall is plastered with the slogan “End PARS,” a reference to the Preliminary Arraignment Reporting System, the mechanism whereby the city shares arrest data in real time with ICE. In New York, the immigrant rights group Movimiento Cosecha organizes campaigns to pressure companies such as Amazon to end their connections with the agency. A group of researchers is training people around the country to find out if their politicians profit from family detention. And activists in cities such as Columbus, Ohio are pushing officials to make the city a true sanctuary in practice, not just in name only.

The movement can point to some wins. Contra Costa County, outside of San Francisco, announced they’re ending a contract that currently allows ICE to detain some immigrants in the county prison. Facilities in Springfield, Oregon; Williamson County, Texas; and Arlington, Virginia have done the same. (Though some who support abolishing ICE do sound a note of caution — what will become of those detainees when the contract ends?)

“When I say we gotta fight local, I’m saying this as someone who has been organizing for 10 years now,” said Jasmine Rivera recently, on a webinar for people who plan to lobby Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf. She works with Shut Down Berks, a campaign that aims to close a detention center in the Philadelphia suburbs.

“We have seen historically that when you fight locally, that is how you have the most impact on the national,” Rivera continued. “But let’s be honest. We’re not going to change the hearts and minds of Trump or ICE. So when we take a local strategy of city, county [and] state, creating these ICE-free spaces where we say no, our police are not going to cooperate with ICE, we are not going to let you use our detention centers, we are going to make it impossible for ICE to operate.”

In their modern iteration, sanctuary cities date back to the 1980s, as a response to waves of refugees arriving from Central America with no promise of asylum, though one could also argue the tradition dates back to states that refused to cooperate with the Fugitive Slave Act.

The Trump Administration’s policies have forced many cities and municipalities to pick a side. Cities such as Oakland have ended agreements to cooperate with ICE, while cities such as Miami, facing pressure from the Trump administration, have ended their sanctuary policies instead. Cities in Texas, where state law prohibits sanctuary cities, are getting creative with other ways to protect undocumented immigrants.

The problem for those immigrants is that “sanctuary city” remains a title that’s easy to claim, hard to define, and even harder to enforce. In declaring themselves sanctuaries — as over 560 cities, counties, and states have done — these localities can mean very different things. Some instruct police not to ask about immigration status, others vows that local law enforcement will not detain suspects for the federal government, or otherwise do the work of immigration enforcement for them.

But ICE can detour around those promises in myriad ways. So advocates and organizers are pushing their cities (and counties) to follow through on the sanctuary commitment.

The protest encampment outside City Hall, Philadelphia. In early July police cleared out the original encampment outside federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement offices. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Take Philadelphia. Mayor Jim Kenney has been a vocal and outspoken opponent of the Trump Administration’s policies, particularly around immigration. He recently scored a victory when a federal judge ruled that the Trump Administration can’t withhold money from the city over its sanctuary policy. Even as a council member, before Trump took office, Kenney championed ending ICE holds in the city, a policy by which noncitizens were held for an additional 48 hours after they ordinarily would have been released from jail. That gave time for ICE agents to pick them up for deportation.

But meanwhile, Philadelphia has a contract that allows ICE real-time access to data on arrests, charges, preliminary arraignment hearings, and bail. Local police may not be turning people over directly to ICE, but information shared through the Preliminary Arraignment Reporting System, or PARS, still contributes to their detention and deportation.

ICE field office director Simona L. Flores acknowledged as much in a letter this week, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported. Though she denied that ICE is using the database to go after victims or witnesses to crimes, she said that the agency “lawfully uses” information from the database, including about an arrestee’s country of birth, “as part of its investigatory efforts.” She also claimed that it was within ICE’s rights to arrest any law-abiding undocumented immigrants they may encounter while pursuing others accused of crimes.

“PARS is being used in a very racial way, because what it collects from immigrants are country of birth and names,” says Blanca Pacheco, assistant director of the New Sanctuary Movement. In other words, PARS doesn’t actually say whether someone has citizenship. “[But] just from country of birth and names, it gives enough suspicion to ICE to think that this person might be undocumented,” said Pacheco.

Then, ICE may show up at their home — or at court.

“This happens often, people getting arrested out of their homes while going to court or when done with their cases,” says Pacheco. “We have another case where a person finishes probation and does everything he needs to do that the judge ordered, and then one day he was leaving for work and he gets picked up outside of his home.”

Ending ICE’s contract with PARS wouldn’t end deportations, it would just cut off access to certain information. The current contract ends on August 31, and the New Sanctuary Movement, Juntos, the Philly Socialists, and myriad other organizations are pushing Kenney not to renew it. This isn’t the first time the New Sanctuary Movement has fought to end ICE’s PARS contract. They’ve been doing so since 2013. But Pacheco says the atmosphere feels different now.

“We have a different mayor, we have a different district attorney,” she says. District Attorney Larry Krasner has already said he supports ending the contract. All it would take now is Kenney’s support.

He has yet to make a decision, citing concerns about disrupting the ongoing legal battle between Philadelphia and the federal government over its sanctuary city policies. “We are careful in our interactions with ICE while the litigation is pending because the decision has had national implications, including for other welcoming cities,” the mayor’s office said in a statement.

It continued, “As we’ve stated many times, we disagree with ICE’s aggressive tactics, their separation of families, and their targeting of law abiding immigrants. We will not become an extension of ICE’s immigration enforcement. ICE access to PARS – should it continue – in no way lessens our disdain for ICE policies and our commitment to maintaining Philadelphia as a Welcoming City.”

In other cities, really creating sanctuary may mean applying pressure on the county level. Last year the mayor and city council of Columbus, Ohio passed an ordinance declaring the city a safe refuge for immigrants. But they wouldn’t go so far as to declare it a sanctuary city. And even if they had, says community activist Ruben Castilla Herrera, it wouldn’t count for much.

“Sanctuary city, in the sense that Trump is against and in terms of policy, it basically means whatever the entity that incarcerates people will not cooperate with ICE. And that entity in Columbus isn’t the city, it’s the county. So [Mayor Andrew Ginther] can’t technically declare this a sanctuary city.”

Now, particularly after several high-profile mass immigration raids in northern Ohio — and the blowback they generated — Herrera and the collective of organizations he works with hope that Democratic politicians at the county level can be pushed to put their policy where their mouth is.

In this case, that would mean the county commissioners and the new sheriff. They could decree that county police won’t cooperate with ICE either. Right now, says Herrera, they are. He’s seen county police entering and exiting the small ICE field office in Columbus with detainees — the same office that he and the organizations Mijente, The American Indian Movement of Ohio, Earth First!, and the Columbus Sanctuary Collective blockaded earlier this month.

Once the story of family separations burst into the news, another hashtag started appearing beside #AbolishICE — #KeepFamiliesTogether. Now that the Trump Administration has said they are ending the separation policy, organizers outside Philadelphia argue that the problem isn’t separations so much as detention itself — and they’re trying to end the practice in their backyard.

Once arrested by ICE, a person may be sent to an ICE-operated detention facility, or to a private, local, or federal prison that ICE contracts with. There are currently just three detention centers where families are kept together: two new privately owned ones in Texas, and one publically owned facility outside Philadelphia, the relatively small Berks Detention Center. While the PA facility has just 95 beds, the two Texas facilities combined have over 3,500.

A protest organized by Shut Down Berks Coalition to pressure Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf to issue an executive order to close the Berks County ICE facility outside of Philadelphia. (Credit: Shut Down Berks Coalition via Facebook)

Berks County operates the center; ICE pays the county $1.1 million per year to utilize it. The roughly 50 detainees there now — half fathers, half children — are mostly asylum-seekers from Guatemala, facing no criminal charges. Though families are detained together, in some cases they can be held indefinitely — sometimes for years. There have been allegations of improper medical care at the facility, and in 2016 a guard was convicted for a rape there. The same year, the PA Department of Human Services announced it would not renew the Berks Detention Center’s contract, but the facility remains open.

The Shut Down Berks Coalition, a group of faith-based and immigrants-rights advocates, is trying to change that. They call for Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf to shut down the center via executive order, something within his power. Via a spokesperson, Wolf has said he does support ending family detention at Berks and revoking its license, but he has not yet taken action.

“Any time we can remove bed space from ICE, means less immigrants are going to be detained,” said Jasmine Rivera on that webinar earlier this month. She was speaking to people planning to lobby Wolf to close the facility. Later that week, 17 people were arrested demonstrating outside the facility.

But on that webinar call, some worried about what would happen to detainees if the prison did close. Wouldn’t they just be moved to a facility somewhere else?

“We wouldn’t be advocating for this if we weren’t 100 percent certain that families would be released,” said Rivera.

She cites the fact that ICE has the power to release people and allow them to live freely while their cases are adjudicated. It’s cheaper, even if people are fitted with monitoring devices like ankle bracelets, and data shows a majority of people show up for their court cases: between 60 and 75 percent of all migrants facing legal action, and, by some numbers, nearly 100 percent of asylum-seekers. Rivera argues if Berks shuts down, detainees currently held there should be given that chance.

On the other side of the country, organizers in Contra Costa County, California, which covers parts of the Bay Area, are about to find out what ending such a contract really means. The West County Detention Facility in Richmond had been allowing ICE to utilize some of its beds; the Contra Costa Immigrant Rights Alliance was fighting for the county to end that agreement.

Then, suddenly, the county did — without consulting with the more than a dozen organizations in the alliance. That worried organizers.

“The biggest concern is making sure that the folks that are still being held there, that they not be transferred to another facility outside of California,” says alliance coordinator Tony Bravo. “What we are demanding is for ICE to let them all go, and let them be able to fight their cases with their families, at home. And we know ICE has the discretion to let them do that.”

The person to lobby is Sheriff David Livingston, who announced the decision to end the contract, but who Bravo also says frequently violates SB54, California’s sanctuary law. Another California law, the TRUTH Act, requires that communities be informed if their local law enforcement collaborates with ICE, triggering a public forum. Contra Costa County will host the first ever TRUTH Act Forum this month, where Bravo said they will pressure Livingston to make sure detainees are released, not transferred, when the contract ends.

The West County Detention Center in Richmond, California. Contra Costa County has ended its agreement with ICE that allowed the federal agency to house here immigrants facing deportation. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

It’s not just counties that contract with ICE who stand to profit from immigrant detention. Immigrant incarceration is big business, and a group of researchers based in Philadelphia, Buffalo, and elsewhere have set out to inform the public about whose bank accounts are fattening as a result of current policy.

“Some of these companies, they’re actually really integral to allowing Trump’s deportation campaign to continue,” says Molly Gott, a researcher with the Public Accountability Initiative and Philly Power Research. One project of the PAI is a website called LittleSis, what Gott calls “the involuntary Facebook of the one percent.” Here, she and other researchers track the connections between powerful people, like a reverse Big Brother that trains its eye upwards, instead of down.

“We wanted to look at the corporations that are profiting off of those policies that people are so outraged about,” Gott says. “And what are the ways that they can be pressured to really take a side and decide if they’ll be on the side of Trump’s immigration policies or if they’re going to break with him and not profit off of and enable those policies.”

So she and others compiled a report that details who is making money off of family incarceration. The large child detention centers, for example, are mostly run by the nonprofit Southwest Key, which reported $242 million in revenue in 2016, and will receive $458 million this year through the Department of Health and Human Services to run its shelters for separated children. CEO Juan Sanchez made $786,822 in 2016.

The report also points to the private prison corporations that operate the majority of immigrant detention beds, such as GEO Group and CoreCivic. Of course, incarceration is the core of their business model, so Gott doesn’t expect to successfully pressure them into ending the practice. But there are other targets, such as the banks who finance those corporations.

“Because of the way GEO Group and CoreCivic are structured, they have very little cash on hand at any given time, so they really depend on this money from banks like Wells Fargo, like JP Morgan, US Bank, to carry on their daily operations,” says Gott. “They have customers everywhere, and people are probably not happy that they are using their money to further this system.”

Evidence shows campaigns like this can be effective: cities including New York City, Philadelphia and Seattle ended contracts with Wells Fargo after their fake accounts scandal in 2016. Might cities break with banks that fund incarceration?

Philly Power Research also put out a second report, pointing out local corporations with ties to current immigration policy — such as Vanguard, a massive money-manager in the Philadelphia suburbs that is the biggest shareholder in both GEO Group and CoreCivic.

LittleSis held a webinar to teach people how to go one step further and find out if their elected officials are taking money from any of these groups. Gott says that while some politicians have stepped up and announced their disdain for ICE policies, “a lot of them are kind of on the sidelines, not doing much, or are people who are getting elected on anti-immigration. platforms. So again, we want to get them to choose a side, not just with Trump, but with these companies that are profiting off of Trump’s policies,” she says.

When she started the research to find out who those politicians might be, she was surprised.

“We expected that a lot of them would be Republicans and hardline anti-immigrant politicians, but there also were a lot who were Democrats and have a more ‘progressive’ face. So I think it’s even more important to pressure those people,” she says.

One example she cites is California gubernatorial candidate Gavin Newsom, a Democrat. He was a speaker at a “Keep Families Together” rally, but it later emerged he had taken a $5,000 donation from GEO Group. After pressure, he donated $5,000 to the Keep Families Together Coalition. The state’s Democratic Party later announced that it would no longer accept political contributions from private prison corporations, and would donate any money received since May 21, 2017 to groups fighting to protect immigrants.

More than 200 people around the U.S. signed up for the webinar, which taught them how to navigate Open Secrets and Follow the Money, two websites that allow people to track political contributions on the federal and the local level. From there, Gott hopes people find localized ways to pressure elected officials.

(Photo by Master Steve Rapport/Flickr)

“We think this is really a moment, we can see from the outrage around this. There are so many people who are mad and want to do something about it,” says Gott. “So we want to share these tools with as many people as possible. People have to have the information first before figuring out how to [apply] pressure.”

In New York, Movimiento Cosecha is trying to pressure companies as well. They have organized a national day of action on July 31 they’re calling No Business with ICE. They’ve published a list of corporations profiting off of ICE’s policies, and are calling on people to boycott or otherwise pressure those companies (the companies, they emphasize, not their workers).

The list includes corporations from Amazon (which provides facial-recognition software to ICE) to Comcast (which supplies the agency with internet services). In some cases, the employees of those companies also have called on CEOs to end the contracts.

Shining a light on the inhumane conditions and callous profiteering of the privatized ICE detention and deportation system has elevated another, larger issue: abolition of the entire mass-incarceration system, from detention centers to holding people who can’t post bail to solitary confinement to prisons as a whole.

Both Bravo of the Contra Costa County Immigrants Rights Alliance and Rivera of the Shut Down Berks Coalition hope that ending these contracts, and ultimately abolishing ICE, would add momentum to the larger campaign of abolition.

“Just because the immigration section of the jail has been terminated and will eventually be gone, doesn’t mean the abuses happening at this facility will end, right?” says Bravo.

The first priority is to get those people free and keep them from deportation, he continues, “But then trying to find ways to intersect our fight with what’s happening to black communities in this country with mass incarceration, and eventually abolishing jails. That would be super ideal.”

Gott agrees that if all this pressure — on politicians, on corporations, on ICE itself — succeeds, the next step will be to turn the same attention to prison abolition.

“It’s really a moment when immigrant rights advocates and racial justice advocates who are fighting to end mass incarceration are coming together around these companies that are doing bad things to both communities,” she says.

Jen Kinney is a freelance writer and documentary photographer. Her work has also appeared in Philadelphia Magazine, High Country News online, and the Anchorage Press. She is currently a student of radio production at the Salt Institute of Documentary Studies. See her work at jakinney.com.

Follow Jen .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine