Yesler Terrace residents and neighbors gathered in August 2018 to celebrate the opening of a new playground and park.

Credit: City of Seattle

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberHundreds of American cities joined an Amazon-run beauty contest for a piece of the explosive growth, in population and income, Seattle has experienced recently. Now renters in Queens and suburban Washington, D.C., winners of the Amazon HQ2 fight, brace for a displacing infusion of well-paid tech workers.

Inside Seattle, the tech bubble has pushed rents beyond the means of thousands who had built a life here. The city is at least five years into a housing crisis that has seen rents climb for residents and, in many areas, businesses. This economic boom saw the city population jump by 20 percent since 2010, while at the same time city housing stocks rose only 16 percent over the same period. Seattle’s acute affordable-housing and homelessness troubles have been well documented; Seattle how has the nation’s third-largest homeless population after New York and Los Angeles. City attempts to address the issue have included passing, then almost immediately repealing, a “head tax” aimed at large tech employers that would have funnelled $47 million a year toward housing and homeless services.

Perversely, this land rush also enabled the city’s public housing provider, Seattle Housing Authority, to accelerate plans to demolish, reimagine and rebuild Yesler Terrace, America’s first racially integrated housing project and Seattle’s most visible public housing site. Since construction was completed in 1942, Yesler Terrace has been a safe harbor for waves of people displaced by violent political tides abroad or disabled by age and luck at home. Rows of low-rise row houses housed refugees from the world’s wars and Seattle’s streets. Generations of young, struggling families found a home between those shared walls on the terraced 39-acre site, as did workers whose backs and hands gave out before Social Security kicked in.

But history cannot repair a crumbling wall or restore a jumble of condemned sewers. Second-story bathrooms — standard at old Yesler Terrace — and winding, narrow outside staircases don’t work well for a neighborhood where a quarter of the residents have mobility issues. By the mid-2000s, it was clear to the Housing Authority that the Yesler Terrace rows had to go.

To pay for the rebuild, public lands have been sold to private developers. A decade into the $1.7-billion effort, about half of the property has been redeveloped. Only a handful of the remaining row houses are still occupied. Most are boarded up, waiting for the demolition crews that are expected to finish the teardown by early 2020. The fenced backyards behind each unit, once lovingly tended by longtime tennants, now grow wild inside a temporary ring of chain-link.

The new development of five- to seven-story towers and 15- to 22-story high-rises includes Housing Authority-owned buildings and will more than triple the amount of affordable housing on the site. The land that previously held 561 homes reserved for the city’s poorest people will eventually support up to 5,000 apartments, most of which will be rented at market rate.

New public housing — much of it in towers with some of the city’s best views — has gone up next to privately owned apartments. About 300 Housing Authority apartments in three complexes are finished and now open to low-income residents, whose rent is typically set at 30 percent of household income. Another 540 or so units, most rented at market rates, in privately owned buildings are either complete or under construction. The plan, finalized in 2012, anticipated a 20-year build, though the pace of construction is set by the speed of land sales to developers.

While the worst fear of Yesler Terrace residents — that they’d lose their public housing entirely — has not been realized, the redevelopment appears to have accelerated gentrification in the adjacent neighborhoods of Little Saigon and the International District. These enclaves, like Yesler, provide an ethnically, economically inclusive place in an increasingly rich and tech-dominated Seattle.

New money is polishing Seattle’s core; the Yesler Terrace rebuild is a small facet of that. Demolition of the city’s elevated waterfront highway — a crumbling visual barrier between downtown and the tourist piers — is set to begin in February. Pedestrian-unfriendly overpasses dividing residential neighborhoods from downtown have facelifts scheduled. Mirrored towers race toward the sky as city hall clears the way for a taller, denser Seattle.

Seattle’s downtown and close-in neighborhoods are among the city’s wealthiest. Yesler Terrace, a stroll from the downtown core and the medical centers atop First Hill, was a longstanding exception to that rule. Another is the International District, an Asian-American community unmoved despite ugly efforts to displace it since Seattle’s founding. Gentrification and displacement have arrived in Little Saigon, the neighborhood sandwiched between the International District and Yesler Terrace, which has been a cultural center of gravity for the region’s Vietnamese population.

“We know that it is coming, but how do we minimize it?” says Quynh Pham, executive director of Friends of Little Saigon, a community group organized in 2011 to protect and enhance the neighborhood. “There are no really good tools out there that can control some of it. …”

“I know that the intention there is not to gentrify the neighborhood,” she says. “But because of the … really nice structures that are going up [at Yesler Terrace], it automatically gentrifies. It won’t be the same.”

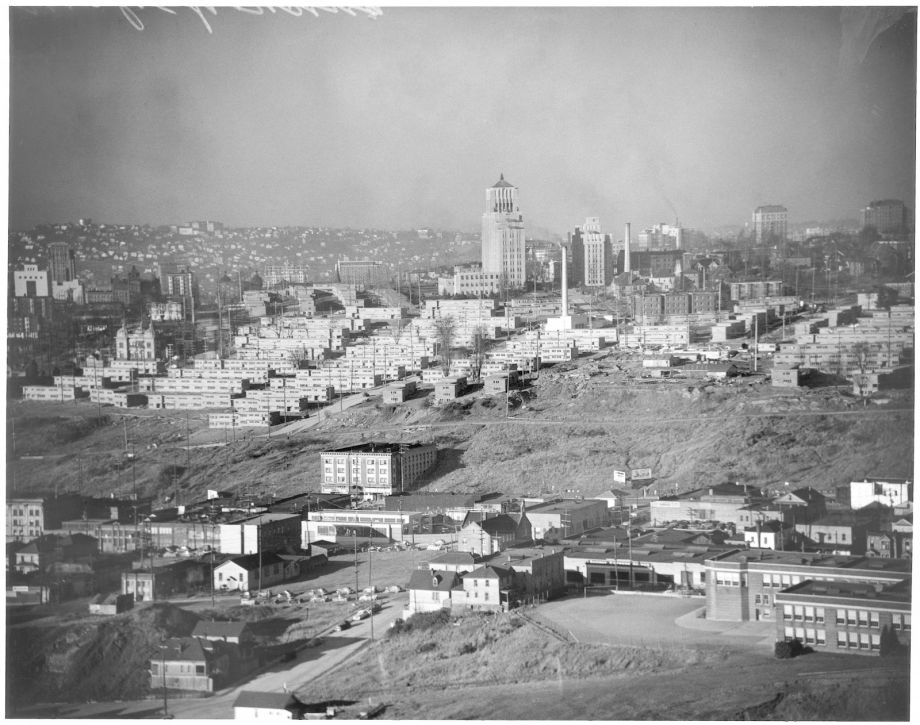

Yesler Terrace (the terraced buildings in the upper left of the photo) was Seattle's first public-housing project, and the country's first racially integrated housing project. (Credit: Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, Museum of History & Industry, Seattle; All Rights Reserved)

Yesler Terrace was a dream conceived as the Great Depression ended and America went to war. The dreamer, then-29-year-old Jesse Epstein, imagined a haven for poor families jammed into the then-as-now bursting city’s apartments. The result was the nation’s first racially integrated public housing project.

The Housing Act of 1937 launched public housing initiatives across the United States. Epstein, then two years out of the University of Washington law school, set to work creating the framework on which Seattle Housing Authority would be built. Epstein went on to become the organization’s first director and the driving force behind Yesler Terrace.

Recalling the experience in 1973, Epstein still tread softly in describing how he integrated Seattle’s inaugural housing project. He simply decided there would be no segregation or racial discrimination in tenant selection. He saw no need to ask the authority board.

“I suppose I can say this now, I was also a little concerned that if I raised the question there might be some consideration given to such matters as quotas, maybe even segregation,” he said, offering an oral history to a University of Washington researcher. “In other words, I felt I would like to handle this administratively. And the board was satisfied to let me do so.”

Epstein went on to describe a community meeting he led attended by more than 1,000 African-American Seattle residents as Yesler Terrace was being built. The hall got heated. Attendees asked that buildings be designated for black residents, or that a quota be set so African-Americans would not be cut out. The crowd was stunned into applause when Epstein shared his plan for integration.

“They thought it was something that wasn’t going to even be considered, so they were going for the next best thing,” recalled Epstein, who died in 1989.

The two-story wooden row houses went up fast. The 68-building project was filled immediately — public housing was reserved for war industry laborers in the runup to the U.S. entry into World War II. The units remained full until shortly before demolition began, in 2013.

As the years passed, U.S.-born Yesler residents were joined by refugees driven there by war and famine. Vietnamese in the 1970s were followed by Ethiopians and Eritreans in the 1980s. Somalis and Slavs displaced from the Balkans arrived in the 1990s. Refugees from the Middle East, now delayed, are anticipated. At last count, 26 languages are spoken in the neighborhood.

“It’s madly diverse, and everyone does not have the same goals or ideas about what should be,” says Kristin O’Donnell, a 78-year-old Yesler Terrace resident who moved there in the early 1970s. “But we care for the kids, we want some peace and quiet, and we are really glad we won the (Seattle Housing Authority) lottery and have roofs over our heads.”

Amarech Bahtai came to Yesler Terrace in 1993. Her arrival marked the end of a journey that began a decade before, when she fled Ethiopia for Sudan and, ultimately, the United States. She raised her two children from a Yesler row house while caring for infants at Seattle daycare centers. Her son and daughter now make their homes in the suburbs. Having moved into a newly built apartment, she has no plans to leave Yesler Terrace.

“I like it here,” Bahtai says. “It’s important for me, Yesler.”

“We did not get what we wanted, which was another round of fix-up. … But realistically, the resources and the federal financing to do that aren’t there. The alternative to doing what they did would be to let the community deteriorate one building at a time, and then board it up.”

Regardless of national origin, Yesler Terrace residents were alike in their extremely low incomes. Longtime affordable-housing activist John Fox cites a 2008 King County assessment that found the average household income at Yesler Terrace was 18 percent of the area’s median. The community served the poorest people in public housing.

Seattle’s supply of subsidized housing is a fraction of the demand. Qualifying renters in Seattle wait two to eight years for spots in Housing Authority buildings. Rent subsidy vouchers are issued by lottery; the most recent drawing, in 2017, saw 22,000 households put in to be on a waiting list for 3,500 vouchers.

In the last round, lottery participants were asked to describe their living situation.

“Some of the people were actually unsheltered — homeless, living on the streets — but a lot were in what you’d call really substandard situations,” says Kerry Coughlin, Housing Authority communications director and an executive board member. “Literally, in one case it was, ‘I’m living in a 9-foot-by-10-foot walk-in closet in a distant relative’s home, with my three children.’ …

“It’s amazing, once a family has stable housing how much they are able to accomplish. But when you’re living in that closet or in a car, or moving from shelter to shelter or relative to relative, it’s really hard for the kids to do well in school. It’s almost impossible for the parents to find work, because just survival is full-time work.”

A Yesler Terrace revival had been on the Seattle Housing Authority to-do list for years before the redevelopment plan began to coalesce in 2006. Water flowed through building foundations. Rats nested in abandoned pipes, and wandered through walls. The buildings were out of compliance with building codes and could not accommodate residents with mobility challenges.

“The buildings were crumbing,” Coughlin says. “The buildings were molding. The infrastructure underneath was cracked and bad. It couldn’t be rehabbed anymore.”

A First Hill resident of 20 years, Jim Erickson is something of a civic busybody; his attitude is that, as a retiree, it doesn’t cost him anything to go to a meeting. He enthuses on the small fights — a new pocket park, a parking garage entrance kept off a walkable street — that subtly shape a city. In 2012, he secured a place on the Yesler Terrace advisory board meant to enable residents, neighbors like Erickson and organizations with a stake in the work to nudge the Yesler redevelopment.

“Pea patch” gardens grow at the foot of Hoa Mai Gardens, a 111-unit apartment complex owned by Seattle Housing Authority. Hoa Mai Gardens opened in the summer of 2017 as part of the Yesler Terrace redevelopment. (Photo by Levi Pulkkinen)

For years, committee members fought and fussed over building designs and amenities. The continuation of a resident council was a flashpoint. The finished product was a compromise, but one many involved take pride in.

“I think we made a difference. I really do,” says O’Donnell, a vocal member of the resident council who opposed the redevelopment and now lives in one of the new buildings. “We did not get what we wanted, which was another round of fix-up. … But realistically, the resources and the federal financing to do that aren’t there.

“The alternative to doing what they did would be to let the community deteriorate one building at a time and board it up.”

Erickson is particularly glad the new buildings were built to keep the interior air clean; Interstate 5 runs along Yesler Terrace’s southwestern edge, soiling the air with exhaust.

Residents nursed smaller, personal fears. Would the new homes have backyards, like Yesler row houses? (No.) Would the new buildings be secure? (Yes.) Would there be parking for the truck that delivers surplus vegetables once a week? (Yes.)

Residents also shared a big, looming concern — when their Yesler Terrace row house is knocked down, would they be shuffled to public housing removed from the city core? Five years into the rebuild, the answer to that question appears to be a matter of perspective.

The Housing Authority contends the 493 households living at Yesler Terrace when redevelopment began have the first right to homes at the new site. Initial rounds of displaced residents had to move off-site. Since those initial relocations, Coughlin says, residents have been able to move into newly built buildings at Yesler Terrace when time came to demolish their homes. Some residents took their housing vouchers and left the city. Others settled into other Seattle Housing Authority buildings. A handful bought homes elsewhere.

But of the renters living at Yesler in 2012, little more than half remain, according to Housing Authority figures. Only 20 percent of residents who moved out of Yesler Terrace when their homes were demolished have returned; many of those displaced residents had settled into other Housing Authority-owned homes and were not inclined to move again when space opened up in new Yesler buildings.

Fox, the housing activist who has been prodding Seattle Housing Authority since 1977, questions the offered rationale for the redevelopment. In his view, Yesler Terrace could have been rehabbed and built up modestly without selling to private developers. Fox argues additional public housing could have been built on the site while retaining the existing homes.

“We now have effectively a higher-density development serving primarily the affluent with a few affordable housing units scattered around,” says Fox, of Seattle Displacement Coalition. “It is part of Seattle’s brave new world of luxury high-rises.”

As planned, the finished development will include 561 units reserved for residents with extremely low incomes — the exact count offered at the old Yesler Terrace — as well as 1,240 units split between tenants at various lower-than-average income levels. Private developers are expected to open 3,200 market-rate units, and that rate is expected to be high.

Yesler’s location is among Seattle’s best. Residents with views will see mountains and water; some will have a sightline on the city’s sports stadia. Yesler Terrace sits on a nascent urban trail flowing through First Hill, known as “Pill Hill” by the medical set who populate its three large medical centers and countless clinics. A streetcar line that will soon sweep through downtown employment centers and already reaches the city’s nightlife districts stops at the center of Yesler Terrace.

In sales to developers, Seattle Housing Authority negotiated affordable housing requirements that exceeded the city rules, Coughlin says. Builders committed that 26.5 percent of the new units would be reserved for affordable “workforce” housing for 20 years. Households with earnings less than 80 percent of the area median household income will rent those units at reduced rates. A single person earning $56,200 a year would qualify; a family of four could earn up to $80,250.

At the new Yesler, public housing and private towers blend subtly. Loud sculptures brighten a courtyard faced by half-filled storefronts at the private developments. The buildings completed so far are vibrant, solid and, in the flavor of construction that has yet to see many seasons, sterile. Passing hands have not smoothed the handrails. New trees and shrubs have not pushed the limits of their planting strips. The terraced playground and splash park opened in August 2018 haven’t been broken in by neighborhood children. The place waits for the finishing touches of thousands of new residents.

The Seattle Housing Authority buildings include units built to accommodate in-home daycare centers; Coughlin says those townhouse-style apartments meet licensing requirements so residents can operate centers as businesses. “Pea patch” community gardens sprout outside the buildings that filled up before fall arrived. The community center, with its computer lab and basketball court, bustles.

Ai-Trinh Nguyen, a Yesler Terrace resident since 1999, says she appreciates the security of her new building, Hoa Mai Gardens, which she moved into in 2017. The old buildings, with their winding footpaths, blind corners and unsecured front doors, were easy picking for burglars. Now she can go on vacation without worrying about a break in.

Some residents relocated to the new Yesler Terrace units regret losing the individual, lovingly tended yards that came with the old row houses. (Photo by Elly Blue via Flickr)

Arriving in the new two-bedroom apartment which she shares with her husband, daughter and son, she was struck by the newness of it all. Her children, 17 and 22, loved it. She couldn’t sleep.

“I missed my old room, my old house,” Nguyen says.

She was provided a plot in the community garden, she says, but it does not match the yard she had outside her old backdoor. Her family, having left the three-bedroom home her children were raised in at the old Yesler Terrace, also lost a room; her son, a student, now sleeps on the living room couch in their new two-bedroom apartment.

O’Donnell said the loss of the backyards hit residents hardest. Some have moved inside the old row houses three times, she said, jumping ahead of the bulldozers to stay in a unit with a yard.

“They are going to be the least happy movers,” remarks O’Donnell, who, as a single mother with a recurring disability, raised her now-grown daughter at Yesler Terrace.

“There is no amenity in the world that the new construction can come up with that can replace having your own little yard with a fence around it,” she continues. “That is something very special. Ain’t no stupid pea patch going to replace that, I’m sorry.”

A showpiece of the redevelopment is the 154-foot hill climb, a stairway and looping wheelchair ramp rising from Little Saigon up First Hill to Yesler Terrace. Bright mosaics built into the concrete retaining walls adorn landings on the path.

“The whole design of that was just wonderful,” says Erickson, of the First Hill Improvement Association. “They had an artist who engaged the community in workshops and created mosaics that expressing the different cultures that were represented in the population. That connected two neighborhoods in a very safe and healthy way.”

That connection, though, is proving a mixed blessing for Little Saigon, a once-neglected commercial district vitalized by Vietnamese immigrants who began arriving in the 1970s.

Then as now, buildings in the area were low-rent and generally low-quality. The new arrivals built businesses between the Seattle’s pan-Asian International District and the mouth of the Rainier Valley, and added a Vietnamese patch to the multi-ethnic quilt extending through southeast Seattle into the suburbs. What the neighborhood offered in affordable commercial space it lacked in housing opportunity. Yesler Terrace saw an influx of Vietnamese refugees, but most settled outside the neighborhood.

Friends of Little Saigon’s Pham recalls driving with her grandmother into Little Saigon every weekend. They stocked up on Vietnamese goods, checked in with friends, visited the doctor.

“It was really a hub for the Vietnamese community,” Pham says.

“Being from a war-torn country, having place has a big significance for our community,” continues Pham, who emigrated as a child in 1990. “There’s still this trauma that gets passed on from generation to generation, so we’ve learned that, even for the younger generation, people want a place to call their home.

“That’s what we’re trying to build in Little Saigon.”

Pham says some Vietnamese Yesler Terrace residents moved during the redevelopment have not returned to the neighborhood.

“We still see some folks coming back, but it wasn’t as many as we had hoped,” Pham says. “We were hoping more community members would come back, but I know it’s harder when people have settled elsewhere for people to come back to the community.”

More concerning is the steady march of demolition and reconstruction through Little Saigon. As Pham tells it, almost every block has a lot that has been redeveloped or sold to a developer. Less robust businesses have closed. Owners who remain wonder if they can survive relocation, or even a temporary displacement.

The First Hill Streetcar, in operation since 2016, rolls through Seattle's Little Saigon neighborhood, which has seen intense development pressure in recent years. A planned expansion of the line will complete a trolley loop through the city's core neighborhoods. (Photo by Gordon Werner via Flickr)

The trouble boils down to ownership. Most Vietnamese entrepreneurs built their businesses in leased space. There isn’t much they can do if their rents rise or their walls are knocked down.

“Even though a business has been around for a long time and become an institution, because of the value of these properties, some owners would rather sell,” Pham says. “They don’t take into consideration the history that has been built.”

Similar concerns abound in the International District as well, though a historic district designation for the center of Chinatown affords it some protection from development. It also benefits from a city-chartered stewardship organization, the Seattle Chinatown International District Preservation and Development Authority.

“Down here, we have not felt that impact yet, but we will,” says Maiko Winkler-Chin, the organization’s executive director. “There’s no place else to develop downtown.”

The International District needs investment. Its electrical system is broken. The sewers are breaking down. Unreinforced masonry buildings, the norm in historic Chinatown, will tumble in the next large earthquake. But infrastructure investments in Seattle have been keyed to development — Winkler-Chin describes being told she would have to wait for a developer to get a new traffic signal at a Chinatown intersection — and development has meant displacement.

“It’s a hard time,” she continues. “It’s the feeling that something is going to happen, and what is your ability to control change?”

“A lot of the people who come down here are looking for something from home, wherever that is,” Winkler-Chin said. “I think (the International District) reflects a diversity that the city hopes for and says it wants.”

Winkler-Chin noted the International District has the city’s highest concentration of elderly residents, and a high rate of poverty. Residents can walk to a doctor who speaks their language and understands their culture. Efficiency apartments there still rent for $250.

In a city facing a housing affordability crisis — the phrase used by Seattle’s leaders — a bold push toward publicly owned housing might seem sensible. O’Donnell, whose life’s work has been advocating for herself and her neighbors at Yesler Terrace, doesn’t see that on the horizon.

“The reality is that the government has decided that subsidized housing is a failed experiment that is not doing well for people on the low-end of the income scale,” she says. “I would like to see that change, but I don’t think it is anytime soon.”

Levi Pulkkinen is a Seattle-based journalist covering the Pacific Northwest since 2002. Formerly a senior editor with the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and a frequent contributor to The Guardian and The Appeal, Pulkkinen’s work has also appeared in The San Francisco Chronicle, High Country News and on the bathroom wall of at least one brewery. You can find him at SeattleJournalist.com.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine