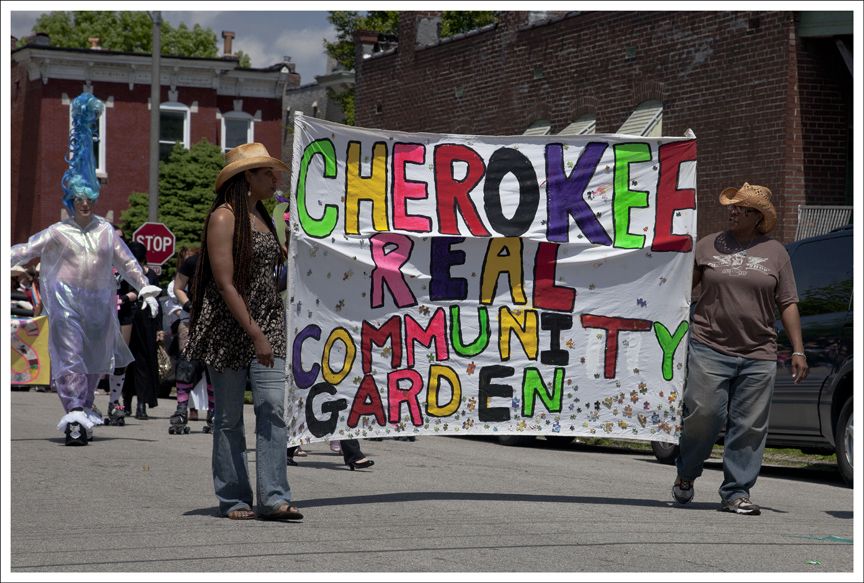

A procession in the People's Joy Parade, part of the Cherokee Street Cinco de Mayo celebration in St. Louis.

Photo by evad 33/CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberEDITOR’S NOTE: The following is an excerpt from “Main Street: How a City’s Heart Connects Us All,” by Dr. Mindy Thompson Fullilove, published in September 2020 by New Village Press. Dr. Fullilove, who earlier this year presented a Next City webinar about her projects 400 Years of Inequality and the People’s Platform for Equity, here presents case studies to illustrate the power of city centers to “name and solve our problems.” She visited Main Streets in 178 cities across 14 countries. In this excerpt, she talks about the evolution of one particular commercial corridor, Cherokee Street, in St. Louis.

I learned about the concept of “planning to stay” from Bill Morrish, whose idea it was. But I got to reflect on the life process of planning to stay as a result of a television series. As Miles Orvell’s book “The Death and Life of Main Street” demonstrates, we can see many of the issues of Main Street taken up in popular culture. “Planning to stay” came up in the television series “The Good Witch,” which is centered on the lives and Main Street businesses of three women, two of them witches. Abigail Pershing, the “not-so-good” witch, arrives in Middleton powered by jealousy of her cousin, Cassie Nightingale, the “good” witch. Gradually, Abigail comes to feel welcomed and secure. While helping to make a “wish quilt” for her cousin’s wedding, she says, “I guess what I want the most right now is to settle in, meet people who feel the same way about Middleton that I do. People who look at Middleton like it’s their home and actually want to stay here.”

Because of the magical properties of the quilt, her wish comes true. She is invited to join a regular card game and becomes mayor of the town.

Sam Radford, the local doctor and her cousin’s intended, notes, “It’s weird.”

“Once I decided to embrace being a Middletonian, this happened.”

He observes, “I didn’t realize you were just visiting.”

She replies, “I was sort of living my life like that. But now I’m here to stay. I even put an offer on a house — your house!”

Bill Morrish and landscape architect Catherine Brown, who was his wife and partner, were working with old suburbs of Minneapolis. He was tired of the usual urban-planning conversation that typically started with listing people’s problems. He wanted something different, a new starting point. What, he thought to himself, if we started with the affirmation that we’re planning to stay? Then we can ask, “What do we need to make that possible?”

Planning a neighborhood is a participatory act of community membership and an expression of belief about the future of one’s community. Before residents and merchants can begin planning for their neighborhood, participants must make a sincere declaration about themselves: “We’re planning to stay.” Planning to stay in a neighborhood can be a transforming experience in which participants discover new dimensions of being a good neighbor and a good citizen. When coupled with planning, “to stay” becomes an active verb. Once this active role is embraced, two questions need to be addressed: 1. What is it about this place that draws us here? And 2. What could we add to this place that will keep us here?

“Planning to stay” became the starting point for community planning. This affirmation of belonging, Bill and Catherine proposed, was the real starting point of taking a sagging suburban city into the future. Having met Bill shortly after I’d published a paper on serial forced displacement in the American city, I experienced this concept as an antidote to the poison of constant root shock. This was the essence of health: affirming commitment to a place. Deborah Tall, the author of “From Where We Stand: Recovering a Sense of Place,” urged us to make a commitment to a known and loved bioregion. That is the only way we can move forward from where we are to a stable future.

Bill and Catherine suggested that people look around their cities, taking into account the existing resources in the domains of homes and gardens, community streets, neighborhood niches, anchoring institutions, and public gardens. Through this survey of what they had, people were able to make comprehensive plans for building on their assets and solving their deficits.

Main Streets were part of the category “neighborhood niches.” In rich prose, Bill and Catherine described the crucial role of commerce set in the neighborhood and part of its functioning. The neighborhood niche was not only a place to buy goods and services but also a setting of encounter and pleasure. Built to human size, and functioning throughout the seasons, these neighborhood niches were critical spaces for connection and community building.

In technical terms, neighborhood niches played a role in building “weak ties.” It was sociologist Mark Granovetter who pointed out the paradox that “weak ties” are what make society strong. This was a surprise to me when I first heard it. His argument was that the myriad casual connections, like those of a storekeeper, are connecting ties, while the strong ties of family and religion create partition, or separation, among groups. While both strong and weak ties are important, it is the weak ties that make the parts into a whole that is greater than their sum, what we call “society.” Neighborhood niches build weak ties par excellence.

In September 2017, I went to St. Louis to give a talk at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, as part of an exhibition by Chicago-based artists Amanda Williams and Andres L. Hernandez titled “A Way, Away (Listen While I Say).” It was planned to honor the demolition of a building, and I was asked to talk about root shock and displacement. While there, Sophie Lipman, a community engagement leader at the Pulitzer, organized a walking tour of Cherokee Street with Anne McCullough, Amanda Colón-Smith, and Pacia Anderson.

The giant statue on the northwest corner of Cherokee and Jefferson streets. (Photo by Mindy Fullilove)

We met at the Mud House, gathered drinks, and went to the back garden to sit, a place walled with warm old brick and filled with plants and wooden benches. The women were a powerful set. Anne was Executive Director of the Cherokee Street Community Improvement District (a business district) and the non-profit Cherokee Street Development League. Pacia was an artist and cofounder of Cherokee Street Reach. Amanda was a somewhat new transplant to St. Louis who had recently taken a position as head of the Dutchtown South Community Corporation, a community development corporation that bordered Cherokee Street. All were connected to Sophie, who was an activist in addition to her work at the Pulitzer.

The conversation bubbled, because each had a piece of the puzzle of how to make a Main Street work and they were deeply engaged with one another. They would take detours to discuss the protests over the death of Michael Brown, murdered by a policeman in Ferguson, or to worry about the engagement of local teens. These would circle back to the work of making a street come alive. By the time we’d finished our coffee, I was in love with all of them and with their street.

The Cherokee Main Street section that we walked extended for 12 blocks. We started in the part east of Jefferson Avenue, which had a number of antique shops. The antique shops were politically reactionary, displaying pro-police flags. The dealers resented the multiethnic, all-ages-welcome place these leaders were creating. Toward the major intersection with Jefferson Avenue, the tone lightened. We encountered a store with take-a-number posters on the window. One had a photo of Lionel Ritchie, and it read, “Hello, is it me you’re looking for?” The words of the song occupied the pieces that you could tear off and take with you. Another offered love and said of the tear-off pieces, take as much as you need.

I was, therefore, in the right mood to arrive at Jefferson Street and look up at the giant Indian statue on the northwest corner. Such a statue is not an everyday sight where I come from. It seemed so profoundly politically incorrect, I had to ask. So far, the Indian was considered an integral part of the area’s history; he was planning to stay, too.

On Cherokee west of Jefferson, where there had been department stores in the days of trolley cars and heavy industry, the street was lighter and the buildings larger. The street had fallen on hard times forty years earlier with deindustrialization and white flight, but it had been reanimated by the arrival of Hispanic businesses. Now a center of Hispanic culture, the street had been given the honorary name “Calle Cherokee.” The street had, more recently, welcomed a more diverse array of artists’ stores, featuring punk and other ideas of what to wear and what to do. All along the way on this side of Jefferson, I noticed signs: we pay the fair wage; rip katt-15 year; and one of Hello Kitty in her pink pussy hat, with hell no, grabby! written on the bottom of her shoe.

At the end of the commercial center of the street was a vacant lot that had been transformed into Love Bank Park, a basketball court for local young people. This was something I’d never seen on a Main Street. We sat on one of the benches and talked about the importance of making young people part of Main Street. The engagement of the organizations Pacia, Anne, and Amanda represented struck me as vital to making a successful Main Street. In a follow-up meeting by phone, we got to go into more detail about the work they were doing, independently and together.

I said to them, “Walking with all of you on Cherokee Street was a very powerful experience on three dimensions: the physical, the commercial, which is mainly what people talk about when they talk about Main Streets, and the social.”

“The physical was just gorgeous; the commercial was very interesting and very attractive; and the social, there’s so much that you were describing that’s going on to animate the street. I don’t know if you think about it in those three dimensions for work, or if you think about it in a different way, but I just wanted to share that that was what has stayed with me.”

Cherokee Street west of Jefferson was once lined with department stores. After falling on hard times forty years earlier, owing to deindustrialization and white flight, it has been reanimated by the arrival of Hispanic businesses. (Photo by Mindy Fullilove)

Pacia responded, “I absolutely think about it in those three dimensions. I’ve actually been thinking about it a lot, because there’s so much that’s changing on this street. There’s a narrative that’s being put out that there’s a heightened sense of—I don’t want to call it social unrest, but you know—crime and the unhoused. There’s the dynamic with the street becoming a community improvement district, so businesses and properties on this street are being taxed a little more and that money’s going into a pool for street improvements, things like that.”

“And then a lot of businesses are closing and Cherokee Street used to be like one in, one out, and now it’s like one out, and then there’s a long wait for another one to come in. So those three areas are specifically where my brain is at, and I think I’m the thorn in the side because I’m always the one talking about a need for a process and standard and direction. And acknowledgment of the history. You know? So yeah, absolutely.”

“For me,” Anne said, “I always thought of the street really on a social level. A big part of my job was building relationships with different nodes. To me, that’s really what makes Cherokee Street what it is — the people — and that’s what I focused on in my work.”

“And I was going to say economic,” Amanda added. “I can never think about Cherokee Street truly without thinking about the neighborhoods, like the residential context that sits on either side. I just refuse to separate the two. A lot of investment has been coming to this area. Permit activity is way up. We did this comprehensive neighborhood planning effort to try to make sure that things were thought about in a holistic manner, and even in terms of, like, the physical rehab of vacant buildings.”

The street was, it developed, touched by four neighborhoods, two of which had been examined in the planning effort that Amanda had led. She was, in my view, justly proud of the plan, which had used a racial-equity lens to look at the densely inhabited neighborhoods, which included many people of color, youth, and households in poverty.

The people in the neighborhoods had varying relationships to Cherokee Street. Pacia, who lived a block from Cherokee, in Gravois Park, said her neighbors never went to the street. One said, “Ain’t nothing up there for me.” The area had a high concentration of artists, and much about the street in the iteration I saw was made by and for them. Another adjacent neighborhood was wealthier and whiter, arguably more interested in Cherokee Street. But the street was also a regional draw, with its magnificent special events, like Cinco de Mayo, and its specialty bars, like Whiskey Ring and Fortune Teller. Similarly, the Hispanic eateries were a draw for Hispanics throughout the area, as well as for others who wanted to enjoy Hispanic food and culture.

This meant that while Cherokee Street was embedded in the surrounding neighborhoods and benefited from their functionality, there was an ongoing insider-outsider tension. It’s possible that this had long been the situation with respect to Cherokee Street, which had historically been a regional shopping area because a trolley stop at Cherokee and California drew shoppers from around the city.

At the end of the commercial center of Cherokee Street was a vacant lot that had been transformed in a “DIY urbanist” intervention into Love Bank Park, a basketball court for local young people. (Photo courtesy Anne McCullough)

I asked about the basketball court, and this brought out many of the issues the women were managing. I pointed out that I hadn’t, in all my Main Street visits, seen a basketball court. Anne explained, “The basketball court was an idea from a business owner, William Porter, who has since moved out from Master Pieza. He saw an empty lot across from his business and wanted to put in a basketball hoop. So myself, Will Porter, and a board member, some kids from the neighborhood, and somebody who generously donated the equipment to put it in just did it without getting a permit or thinking about anything other than just doing it. It was kind of like a ‘Do it yourself’ urbanism kind of experiment.”

“The park had been utilized previously by Pacia for Cherokee Street Reach and other activities, so the idea kind of was already there for it to be utilized as a space for youth. But the basketball court was something that we put in with the intention of having a space for everyone on this street. And it’s been host to a lot of really great events — a basketball tournament, the trick or treat on Cherokee Street, Cherokee Street Reach Camp — and a lot of activities, but it’s a really interesting case study, because we did it without really thinking about how we would manage it. How safe it would be. If it was really something that the residents that live around it would want. Who would use it. How we could make space for everyone. And there’s been a lot of problems with the park, unfortunately, and trying to manage that was really difficult. I’m assuming it’s still really difficult. Not something we really thought one hundred percent through. You know, a lot of times, those DIY projects don’t really last. They’re just temporary, and it’s still there, with the intention of building out a greater, a better, more functional park. But from what I understand, there’re some safety concerns more as of late. Am I right, Pacia?”

Pacia agreed. “It’s really interesting because you think about caregivers and caretakers and just how really important they are. Anne has gone, and Master Pieza is closed, and Street Reach is really busy. So within a couple months’ period, the primary people who have been the caregivers of the park are gone, and that’s everything from picking up the trash to just being present to, you know, breaking up conflicts or trying to manage some kind of programming or renting basketballs.”

As the conversation about the basketball court continued, what surfaced was another problem: the opposition of some Hispanic business owners, some of whom thought the basketball court was bad for the image of the street and might deter their customers. Amanda interjected, “I’m trying to figure out how to not frame it as an accusation, but I think personally — I grew up in New York — I identify as Afro-Latina, and I would say that culturally within a lot of Latino communities, there is a specific antiblack racism. I mean, there’s an anti-youth culture that maybe is present across — I don’t want to say anti-youth, but in terms of seeing the social development piece as a part of business owners’ responsibility is like, ‘It’s not our job to raise those children.’

“Maybe it’s not just the Latino business owners. Maybe it’s everyone, but, like, anti-black racism is a very specific thing that has been very difficult within Latino communities to bring up. I think that just overall, the question about, like, safety and youth is encoded in a much bigger conversation about racism in St. Louis.”

These community gardeners are marching in the People's Joy Parade. (Photo courtesy of Bob Crowe)

For a group of women profoundly engaged with the Michael Brown protests that had rocked the region, the conversation about racism was front and center in their minds. How to balance the many demands was obviously not straightforward, but making a neighborhood plan using a racial-equity lens was profoundly important.

As the time for our conversation was running out, I wanted to close by asking what they were proud of. On this topic, they were just as expansive as on the others, and that represented the ways in which their constant engagement with the contradictions permitted them to make and celebrate a remarkable space. Anne said she was really proud of Love Bank Park. Pacia was really proud that even when people didn’t see eye-to-eye on everything, they could work together to make magic. Amanda was really proud of the comprehensive neighborhood plan she helped produce, which would strengthen and protect the vulnerable of the area. Sophie, who didn’t work on the street and had been quiet through much of the conversation, added that she was proud of them all. She singled out Anne, who had moved to Seattle since I’d first met her, to laud her bridge-building across all the different groups.

A few months later, the Cherokee Street News arrived in my email. In it was a call:

We are calling YOU—the broken-hearted Prince entourage, David Bowie impersonators, Mexican dancers, moving vehicle rock bands, bike brigades, cardboard Bricoleurs, art cars, performance artists, motorcycle crews, Volvo devotees, dancing troupes, Bombastic Marching Bands, dancing grannies, lawn chair performers, kazoo groups, breakdancers, kinetic sculpture builders, gigante artisans, Frida Kahlo and Mermaid Wannabees, and any other lost members of the Cherokee Street tribe … We are inviting you to join us on May 5th at 1:15 pm during the People’s Joy Parade as part of the Cherokee Street Cinco de Mayo Celebration.

I had heard there was such a celebration, but I hadn’t heard about the Joy Parade. Happily, the Internet has everything.

Excerpted from “Main Street: How a City’s Heart Connects Us All,” by Dr. Mindy Thompson Fullilove, published by New Village Press. Copyright © 2020 by Mindy Thompson Fullilove. All rights reserved.

Mindy Thompson Fullilove, MD, LFAPA, Hon AIA, is a social psychiatrist who focuses on the ways environmental factors affect the mental health of communities. She is a Professor of Urban Policy and Health in the Urban Policy Analysis & Management Program at the Milano School for International Affairs, Management & Urban Policy of the The New School. She has published numerous articles and six books, including “URBAN ALCHEMY: Restoring Joy in America's Sorted-Out Cities” and “ROOT SHOCK: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America and What We Can Do About It.”

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine