Listen carefully nearby certain storm drains in Baltimore’s Remington neighborhood, and you might be able to hear the echo of Sumwalt Run, flowing 30 to 40 feet below.

The creek disappeared from Baltimore’s landscape in the early 20th century when the city built a new sewer system. Sumwalt Run became a concrete culvert, moving springwater and storm runoff through Baltimore’s sewers into its harbor.

It’s one of dozens of “ghost rivers,” as local artist Bruce Willen calls them, in the city: buried streams that still “haunt” the urban landscape and its residents by contributing to downstream water pollution and flooding.

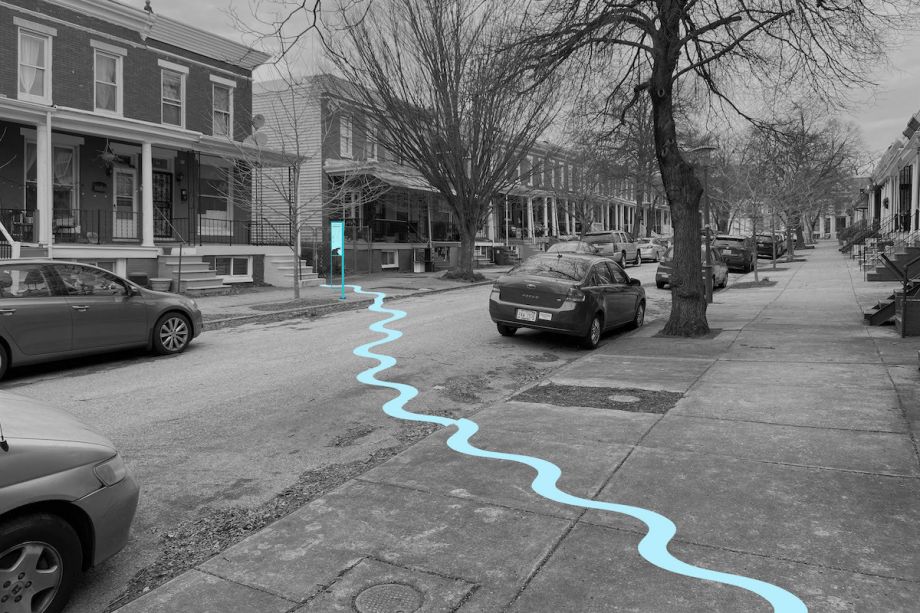

A “Ghost Rivers” installation site (Photo courtesy Public Mechanics)

This month, after two years of intense community engagement, Willen launched a new public art installation and walking tour in central Baltimore that visualizes for passersby the lost creek and forgotten history hidden below their feet.

“Ghost Rivers” creates an overlay of winding pale blue lines, like a river on a map, which traces Sumwalt Run’s path across 1.5 miles of Remington’s urban streets and sidewalks — and helps illuminate the environmental costs of our inadequate urban infrastructure.

“There are stories of buildings in Baltimore mysteriously getting six feet of water in the basement and then the water mysteriously receding,” the project’s website explains. “And it’s not because of a water main break— often it’s due to hidden waters that flow under foundations of old buildings and contribute to flooding issues in the city.”

Today, many North American cities are moving to “daylight” these buried waterways, or at least to create “rainways” reintroducing these natural paths, in an effort to mitigate flooding and filter pollutants from storm runoff. In Baltimore, some are calling for the city to daylight the Jones Falls river, which flows underground through the city beneath the I-83 expressway.

The permanent installation includes nine sites from Charles Street to Falls Road, with three more set to be installed in the spring, with pavement artwork made from preformed thermoplastic (the same material used to mark bike lanes).

Willen, who led the installation and the engagement through design studio Public Mechanics, says his aim was to make the installation accessible to as many people as possible by integrating it into the fabric of the neighborhood.

“This idea of a lifelike map in the physical environment got me excited about the project, and have it be something you might be walking down the street and encounter,” he tells Next City. “It allows people to see the landscape in a different way and peel back some of these layers of history in the built environment.”

The pavement artwork and sculptural signs help visitors visualize the buried stream; a map helps them navigate from site to site; and a QR code links to further information and images.

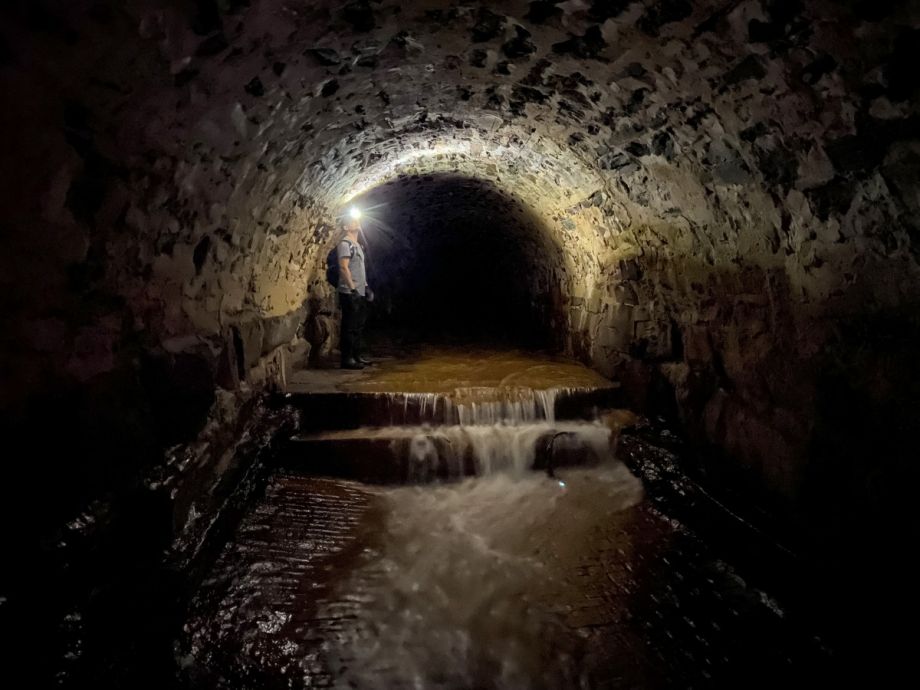

Sumwalt Run today (Photo courtesy Public Mechanics)

Together, Willen says, they school visitors on the ecological history and impact of buried streams, Baltimore’s urban development and demographic transformations, and how longtime residents of Remington remember their buried streams.

“I spent a lot of time in the neighborhood just walking around, talking to people and going to old school bars having conversation about the history of Remington and peoples’ recollection of buried streams,” says Willen, who worked closely with members of the Greater Remington Improvement Association.

It turned out many were familiar with Stony Run, another partially buried stream in Baltimore. But few had heard of the buried creek in their own neighborhood. His hope is that the installation promotes a greater understanding of the buried waterways and infrastructure hidden beneath their feet.

“I hope that it contributes to conversations about the future of our urban watershed and ensewered river,” Willen says. “Are we going to keep maintaining and rebuilding them, are there opportunities to daylight them, are there alternatives? And can we have a more intentional and collaborative relationship with the natural systems that surround us?”

Tracing the path of the Sumwalt Run from sign to sign offers a powerful physical visualization of the impacts of stormwater runoff in Baltimore, says John Marra, eco-literacy and engagement manager for Blue Water Baltimore. It’s a powerful teaching tool for organizations like his, which works to show how the city’s waterways interact with its pipes.

“It can be difficult to fully envision a series of underground pipes that runs beneath most parts of the area, let alone what the landscape looked like beforehand,” Marra says. “The Sumwalt Run is a small waterway, but the Ghost River project tells a bigger story about the impact of intentionally directing stormwater into tunneled waterways.”

Aysha Khan is the managing editor at Next City.

Follow Aysha .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)