Copenhagen has a fully integrated bicycle infrastructure network. And in Denmark, 85 percent of children can ride a bicycle by the age of 5.

Mikael Colville-Andersen

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberEditor’s note: The following is an excerpt from Copenhagenize, by Mikael Colville-Andersen. The book argues for designing “life-sized cities” that place the bicycle at the center of the urban transportation narrative, an approach that urban anthropologist Katrina Johnston-Zimmerman calls “the definitive guide to the future of our cities.” If you’d like to read more, we’re offering a free copy of the book to everyone who gives $60 or more to Next City, as a thank-you gift for your donation.

Here’s the baseline. We have been living together in cities for more than 7,000 years. By and large, we used those seven millennia to hammer out some serious best-practices about cohabitation and transport in the urban theater and the importance of social fabric. We threw most of that knowledge under the wheels of the automobile shortly after we invented it and have subsequently suffered through a saeculum horribilis in the urban context. Our overenthusiasm for technology and our human tendency to suffer short-term urban memory loss have further contributed to our zealous disregard for past experience.

Cities thrill me, but it has always been the streets that fascinate me to no end. Streets are the skeletal structure of the city organism. The veins pumping the lifeblood of a city from one end of the urban landscape to the other. For 7,000 years, the streets of a city were the most democratic spaces in human history. We did everything in the streets. We transported ourselves, sure, but we also bought and sold our goods, flirted, gossiped, discussed politics. Our children played in the streets. They were an extension of our homes, of our living rooms. Urban development was natural and organic and was based on the immediate needs of the people living in the streets in particular and the city in general. Both logistical needs and societal.

Years ago, after I finished film school, I taught storytelling and screenwriting. After we, as homo sapiens, have secured our three basic needs — water, food and shelter — our fourth need emerges: storytelling. For the better part of history, we gathered around a firepit after the day was done — telling stories, forming bonds and further building belief systems and cultural mythologies. Some might argue that sex is our fourth basic need, but telling or listening to stories is an important step toward having sex with someone.

The firepit was our meeting place. Our anchor. As cities emerged and an indoor life became a part of our norm, the streets still remained as our urban firepit in which we told our stories and formed our bonds.

The automobile and the infrastructure required to move it through our cities sounded a death knell for the streets and for our urban firepit. After 300,000 years of homo sapiens and 7,000 years of democratic space, our perception of the streets changed drastically. The automobile industry made quick work of it, too. Two things happened to change the perception. When the automobile appeared in our cities, it was an invasive species detested by citizens. Motorists were despised, and makeshift monuments were erected in many American cities to the alarming number of victims of car crashes — in particular, children.

There was an almost instant traffic-safety problem, and everyone was at a loss as to how to solve it. Engineers were the urban heroes of the day in rapidly expanding cities. Figuring out solutions for how to get electricity and water to our homes and sewage away from them. That couple of generations of engineers were brilliant. Engineers were handed the task of solving the traffic-safety carnage. The best problem-solvers of the day were an obvious choice for tackling such a serious problem. What happened, however, was that streets went from being regarded as a subconscious democratic firepit to becoming treated as public utilities. Not human spaces but puzzles to be solved with mathematical equations.

The automobile industry also had a problem. It had shiny new products to sell, yet everyone hated them. They knew they needed to change the public perception of streets, so they employed marketing, spin and good old-fashioned ridicule to get the ball rolling. During this period, they cut their teeth on vehicle marketing and carved out techniques still in use today. It was one thing that engineers tweaked the way traffic lights functioned in order to accommodate the rising number of cars, but the automobile industry saw an opportunity to sell the idea that streetspace should be allocated to cars exclusively.

The idea was simple: Everyone else get out of the way. It started with op-eds and ads in newspapers urging pedestrians to stay out of the streets and instead using the growing number of crosswalks. Boy Scouts were enlisted to hand out flyers, chastising pedestrians for their behavior. The timeless act of crossing the street in the middle of the block gradually became socially unacceptable. Anyone who resisted this new school of thought was labeled as old-fashioned, standing in the way of progress.

That very American word, jaywalking, was coined simply to ridicule pedestrians slow to adapt to the desires of the automobile industry. “Jay” was a derogatory term for a country bumpkin, someone who didn’t know big-city ways. If we live in cities, the last thing we want is to be considered outsiders. We want a sense of collective belonging. One simple word, repeated ad nauseam, was all that was needed.

The last great obstacle for those wanting to secure streetspace for cars were the angry mothers of America who saw their children killed or maimed by cars in the streets. Enter: the playground. That little zoological garden into which we still place our kids was an invention of the automobile industry as a way to appease mothers and get the little rascals out of the way. Finally, the stage was set. The coast was clear of irritating, squishy obstacles; the greatest paradigm shift in the history of our cities was complete. It took less than two decades to reverse 7,000 years of perceiving streets as democratic spaces. We are still suffering from it. (Peter Norton’s book “Fighting Traffic” is your go-to tome about this fascinating and depressing period in transportation history.)

What also happened was that our societal firepit was effectively removed. Doused in water, buried out of sight and paved over with asphalt.

Firepits have reemerged in some cities. Pedestrian-friendly streets, public transport, and the bicycle have brought back the opportunity to gather with our urban flock. Whether we speak to each other or not, we are elbow to elbow with our fellow citizens, sharing a subconscious urban experience. In the Copenhagen rush hour, on every street small firepits are formed at intersections, allowing citizens to gather in clusters while transporting themselves through the city.

The urban anthropological advantages of having impromptu cycling firepits should not be underestimated. Motorists walk out of a house and into a garage to get into a car for a drive to work. They park and enter an office. There is little interaction with other citizens in such a vacuum-packed life. Cycling through a city, however, you are closely connected with the urban landscape, using all of your senses. Every morning as I pass City Hall Square, cyclists check the clock tower. They either slow down or speed up, depending on their schedule. I don’t communicate directly with other people at red lights, but we are connected. I see human forms, I hear coughs or telephone conversations. I smell shampoo and perfume around me. I get ideas for shopping when I see clothes or shoes worn by someone else. I exchange flirtatious glances or smiles. I will do the same as a pedestrian or aboard public transport, but there is an amazing dynamic on the cycle tracks and at red lights. Jostling for space, keeping our balance, soaking up sensory impressions before moving on to the next firepit.

The Danish novelist Johannes V. Jensen, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1944, has many references to urban cycling in his body of work. In the 1936 novel “Gudrun” he writes: “And, like a large home, Copenhagen begins the day’s work. Already down on the streets, one is at home, with loose hair, in long sitting rooms through which one travels sociably on a bicycle. In offices, workshops and boutiques you are at home, in your own home. Part of one large family that has divided the city among itself and that runs it in an orderly fashion, like a large house. So that everyone has a role and everyone gets what they need. Copenhagen is like a large, simple house.”

Indeed. A home. With a much-needed hearth. And lest we forget, this was the norm in most cities on the planet for decades, from the bicycle boom in the late nineteenth century to at least the 1940s and 1950s. The bicycle was a normal form of transport from Manchester to Singapore, from Sydney to Seville. The modal share for bicycles in Los Angeles a century ago was 20 percent. Small, transportational firepits around which cyclists gathered were warming our cities.

The fledgling vocation of traffic engineering, granted carte blanche by the new paradigm, continued the radical engineering of our streets. Standards were developed in America through the 1930s and 1940s, in tandem with the rising belief that cars were the vehicle of a glorious future. The standards started to travel and were readily adopted by countries around the world. This development accelerated through the 1950s and 1960s. Cycling traffic in most cities of the world peaked in the late 1940s and then began a sharp decline. Even in Copenhagen and Amsterdam; 55 percent of Copenhageners rode a bike in 1949. By 1969, that number had fallen to around 20 percent, as roads were widened to accommodate cars. The most surprising thing about traffic engineering is that it is largely unchanged in the decades since the 1950s. In our modern society we would be absolutely outraged if one vital profession lagged so far behind. Imagine if medical care were still using the same techniques and science as it did in the 1950s. Or education. Or parenting. That would be bizarre and unacceptable. And yet we accept that traffic engineering has failed to modernize. Or perhaps just failed.

When you start to scratch just a little below the surface, you discover that we live in cities that are controlled by strange and often outdated mathematical theories, models and engineering “solutions” that continue to be used despite the fact that they are of little use to modern cities. One of them is called “the 85th percentile.” It’s a method that cities all over the planet use to determine speed limits. Nobody questions it. Certainly not the engineers and planners who, for decades, have swallowed it whole during their studies.

The concept is rather simple: the speed limit of a road is set by determining the speed of 85 percent of cars that go down it. In other words, the speed limit is solely set by the speed of drivers. This is the basic rule that determines traffic speeds worldwide. Including the street outside your home.

It can, of course, be revised — but that rarely happens. The engineers will just shrug and say that the 85th-percentile method is the only method and it can’t be changed. The numbers don’t lie. The problem is that human beings are not numbers. Here’s the tricky part of the 85th-percentile method. It assumes the following: The large majority of drivers are reasonable and prudent, do not want to have a crash and desire to reach their destination in the shortest possible time; a speed at or below which 85 percent of people drive at any given location under good weather and visibility conditions may be considered as the maximum safe speed for that location.

If they assume that the large majority of drivers are reasonable and prudent, then what about the rest of the drivers? Do we assume that everything is going to be fine by handing over complete power of our streets to motorists? Not to mention mixing anthropological assumptions with pseudoscience?

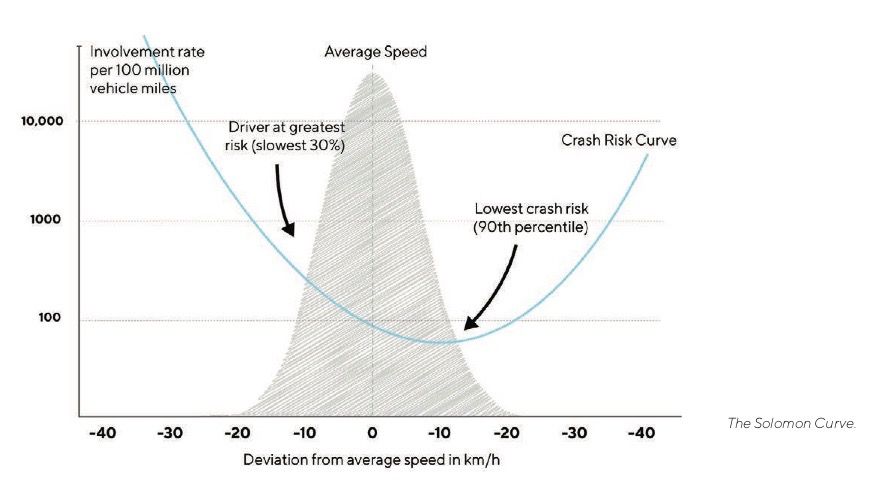

The Solomon Curve shows automobile collision rates as a function of speed. Though the research is more than 50 years old, it still forms the basis for determining speed limits in urban and rural areas. (Graphic by Mikael Colville-Andersen)

This, on the other hand, is the traffic engineer’s perception of “safety” and speed. Looking at the graph, their perception is rather different and rather out of date: Imagine a street where the average speed is 50 kilometers per hour (30 miles per hour). If the speed is reduced by 5 kilometers per hour (3 miles per hour), then, according to this archaic model, the drivers are allegedly exposed to a higher risk. What is most shocking is that this entire concept completely ignores pedestrians and cyclists. Another horrific conclusion from this graph is that when you increase the speed, the crash risk is alleged to be less than for slow speeds.

All of this seems suspiciously like an argument to build more highways and freeways, because “with more speed comes more security,” as they (once) said. The graph, still touted as the “latest research,” is called the Solomon Curve. At the Copenhagenize Design Company office we all guessed how old it was; our guesses ranged between 15 and 30 years old. But none of us was close. In reality, it’s based on a 1964 study by David Solomon entitled “Accidents on Main Rural Highways Related to Speed, Driver, and Vehicle.”

You read that right. “Main Rural Highways”— not city streets. It is still wholly endorsed by the US Department of Commerce and the Bureau of Public Roads, which was administered at the time of the study by Rex Whitton. He was also — surprise, surprise — a federal highway administrator. In essence, a study from 1964 remains the main argument to build more highways and freeways with faster speeds where the ends justify the means, even if the means ignore vulnerable groups such as pedestrians and cyclists and assume that public transport doesn’t even exist. Even if the study is now used to serve the automobile in densely populated urban areas, far from any freeways.

The Institute of Traffic Engineers once wrote that “the 85th Percentile is how drivers vote with their feet.” The ITE failed to mention that, when it comes to establishing speed limits in cities, pedestrians and cyclists are excluded from such an election. They don’t even get the chance to go to the polls. All this is still happening right now as you read this. In your street. With your tax money.

I want to offer up some alternative philosophies. We can rightly assume that there was “engineering” in play over the past 7,000 years that preceded the automobile. Roads and squares were built and buildings to go alongside them.The Romans, among others, excelled at construction and developing techniques. By and large, it was a much more organic process. Engineering responded to the immediate needs of the people who were living there and worked in tandem with them. Necessity was the mother of invention, as it should be. Although no longer, it would seem. We live in an overly tech-obsessed world where we invent things because we can, not because we actually need them. No one has been able to explain to me what the phrase “smart cities” is supposed to mean. It’s a fancy, seductive catchphrase but one without any specific definition.

In order to plan for our urban future, we need to look closely at our urban past. A few years ago I was watching “Back to the Future” with my son, who was nine at the time. The film ended and he asked me what year it was made in. I told him it was 1985. He laughed. “So Doc went 30 years into the future … that’s like … now! But there are no flying cars and goofy clothes … ” Nope. He nailed it. A century of technological — and fashion — promises that failed to deliver. A saeculum horribilis from which we need to recover. Feel free to lump autonomous cars and the hype surrounding them into the same category. When I speak of the importance of going to back to the future, I mean to a place where we were rational and realistic. Back to a time, or times, where we did things that made sense.

Bicycle urbanism by design is the way forward. We are surrounded—if not bombarded— by products to buy in our daily lives. Take a look around you at the many products you have acquired. Your smartphone, toothbrush, remote control, mouse, chair. They all have one thing in common. There was a designer or a design team dedicated to ensuring that you would have a positive design experience when using it. The team that produced my smartphone was employed by a multinational corporation that is intent on increasing profit margins, sure, but the designers bent over backward to make sure that the phone was easy, intuitive and enjoyable to use by me, my ten-year-old daughter and my 88-year-old father. And everyone in between. It was a human-to-human process from idea to purchase. Their sole task was thinking about the human on the other end of that process. That can’t be said of traffic engineering and even traffic planning in most parts of the world, where mathematical models focused on moving cars around is the primary focus.

It’s a simple question: What if we designed our streets like we design everything else in our lives? Like we expect everything we use to be designed? It’s no secret that Denmark is a design culture. The phrase “Danish Design” is swathed loftily in quotation marks. My kids have design classes in the third and fourth grades here in Copenhagen. The three principles of Danish Design are carved in stone: Practical, Functional, Elegant. Humans love chairs and have been constantly designing them for several millennia. As well as interpreting them. Designers and architects have been trying to funk up the chair since forever. All manner of interpretations have seen the light of day, from the interesting to the wacky. We can regard chairs at exhibitions that have been dressed up like an octopus or a shopping cart and either love them or hate them. The point is that none of us have four crazy interpretations of the chair in our living room for guests to sit on.

Seventy-five percent of Copenhageners cycle all winter long. Official city policy is that all the cycle tracks are cleared of snow by 8 a.m. (Photo by Mikael Colville-Andersen)

Imagine if cycling or walking in a city were as easy and intuitive. A well-designed bicycle infrastructure network is like a well-designed chair. It is practical and functional and requires little interpretation to use it. If it is also elegant, then so much the better. In the study “Understanding the Seductive Experience,” designers Julie Khaslavsky and Nathan Shedroff explore the seductive nature of design. To paraphrase: The seductive power of design can transcend issues of price and performance. They have the ability to create an emotional bond with their audiences, almost a need for them.

Do I swoon every time I cycle around Copenhagen on best-practice infrastructure that is kept swept and smooth? No. Nor do I fall to my knees in awe of the beauty of the “7” chair by Danish architect Arne Jacobsen in my living room or sigh wistfully every time I pull out my Samsung Galaxy S8 smartphone. All have seduced me, however. The thrill of the seduction bubbled to the surface in the early stages of my emotional relationship with such objects, but now it has been absorbed into my subconscious. I do not doubt that I experience pleasure when using such objects, but damn, I need them. I need that constant sense of well-being I experience when using them. I don’t need to think about them, they just need to work and to look spectacular. In the case of bicycle infrastructure, I need to be safe and feel safe and get to where I’m going without having to put much thought into it.

The citizens of Copenhagen have been seduced by the bicycle infrastructure network. It is practical and functional, getting them where they want to go quickly and conveniently. There is elegance in the smooth, structured uniformity and high level of maintenance. The smoothest asphalt in Denmark is always found on the cycle tracks. Even when the weather is miserable, which is more often than not in Copenhagen, the seduction continues. Seventy-five percent of Copenhageners cycle all winter. There are better days for cycling in the city, but despite the challenges, it’s still the quickest way to get around. The City knows how to make cycling a feasible option throughout the year. In the winter, the official policy is that all the cycle tracks are cleared of snow by 8:00 a.m. The goal is “black asphalt” by the time the citizens head out to go to work or school. As in many cities, the streets are divided up into categories for snow clearance; it’s just that the bike infrastructure sits at the top of the list. If a snowstorm is more intense, it may prove difficult to keep the infrastructure clear of snow. The citizens know that it’s temporary and that the City is on the way and doing their best. The journey home will be much more pleasant, despite the subzero temperatures.

When you invest in a designer chair, table, or lamp, you take care of it. Why should it be any different with a comprehensive network of bicycle infrastructure? Keep it clean, polished, beautiful. Cherish it. Design is seductive, and design also possesses great power — the power to change human behavior, no less. Wherever you are as you read this, you have probably heard the same kind of comments about cyclists. You might even have uttered them yourself. “Those damn cyclists … breaking the law … ” Insert whatever local expletives might be relevant. The first thing I say when I hear this — and I hear it all over the planet — is that it is completely unacceptable to scold cyclists when the city hasn’t given them best-practice infrastructure or, even worse, none at all. I can’t scold my children for stealing cookies if we don’t even have a cookie jar.

Adapted from Copenhagenize, by Mikael Colville-Anderson. Copyright © 2018 by the author. Reproduced by permission of Island Press, Washington, D.C.

Mikael Colville-Andersen is a Danish-Canadian urban design expert and CEO of Copenhagenize Design Company, which he founded in 2009. He works with cities and governments around the world, designing their bicycle infrastructure and communications and coaching them towards becoming more bicycle friendly. He is also the host of the global television series about urbanism, “The Life-Sized City.”

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine