Howard University Founders Library (Photo by NCinDC / CC BY-ND 2.0)

Black landscapes matter.

Or they should — but centuries of oppression followed by disinvestment have led to the erasure of many places important to Black history, and the histories behind them.

That must change.

If spaces and landscapes are to reflect America as it is, then America as it is must be able to see itself in America's spaces and landscapes.

In the following photo essay, adapted from an essay by Kofi Boone, see the places that make up a start of what we could call the Black landscape architecture canon. The list is far from complete.

The list is broken into three themes, inspired by Black Lives Matter cofounder Alicia Garza, who has said the underlying motivation for Black Lives Matter is fighting “to be seen, to live with dignity, and to be connected.”

The text in this slideshow is excerpted from Enabling Connections to Empower Place: The Carolinas, by Kofi Boone. The essay appears in Black Landscapes Matter, edited by Walter Hood and Grace Mitchell Tada, published December 2020 by UVA Press.

Introduction written by Rachel Kaufman

Middleton Place (Photo by Davey Borden / CC BY-ND 2.0)

White plantation owners specifically plundered West Africa for their rice-farming expertise and strategically bought slaves who were Wolof farmers. Those farmers built much of the rice cultivation areas at Middleton Place in isolation.

Slavery in America was one of the most noxious activities in human history. But the active selection of skilled African people to build landscapes, including Middleton Place, acknowledged their high level of talent and ingenuity, even under extreme duress. Yet American landscape architecture avoids discussion and recognition of the African and Black contribution to the profession. By any other name, the Wolof people who built Middleton Place, as well as the countless thousands who did similar work across the burgeoning nation, were landscape architects.

Princeville, NC (Photo by Virginia Sea Grant / CC BY-ND 2.0)

After the end of the Civil War, recently freed Black people endeavored to create their own communities. During Reconstruction, and with newfound access to political and economic power, Black towns and institutions emerged wherever Black people lived.

In 1865, and immediately after the end of the Civil War, at a former encampment situated across from the Town of Tarboro, North Carolina, and within the floodplain of the Tar River, the land was dubbed Freedom Hill. Twenty years later, a Black community elder named Turner Prince purchased the land, and it was renamed Princeville, the first incorporated Black town in America.

(Continued on next slide)

Zora Neale Hurston Festival, Eatonville, FL (Photo by Florida Memory / No known copyright restrictions)

Eatonville, Florida, was founded by Black Americans in 1887, on just over one hundred acres in what is now Greater Orlando. Eatonville was a fully developed town featuring a bustling business district, churches, and one of the largest schools for Black Americans in the region.

Eatonville rose to national recognition due to the writings of one of its most famous residents, Zora Neale Hurston. Their Eyes Were Watching God was partially set in Eatonville.

In the late twentieth century, Eatonville was declining. Everett L. Fly, a Black landscape architect based in San Antonio, Texas, partnered with Eatonville to generate community development guidelines drawing inspiration from Hurston’s descriptions of the community, and to launch a Zora Neale Hurston festival. The annual festival extended the visibility of Eatonville’s heritage and provided a revenue source to fund future community improvements. In 1988, Eatonville’s Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Oak Grove School Gallion, Alabama. (Photo by Jimmy Emerson, DVM / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

If local communities could raise half of the resources required to build a new school, the Rosenwald Fund, created by Sears cofounder Julius Rosenwald, would match it. In many cases, including in Princeville, residents refused the match and raised the entire budget themselves.

More than five thousand Rosenwald Schools were built across the Southeast. Sadly, many of these sites have fallen into disrepair. But they echo a time when local people—Black people—raised their own funds, contributed their own resources, know-how, and site-planning awareness to hundreds of state-of-the-art facilities in their own communities. They were landscape architects.

Tuskegee University in the early 20th century (Image: Library of Congress Prints & Photos Division)

The first professionally trained Black landscape architect was David Williston (BS, Cornell University, 1898. His many accomplishments include, in a twenty-year collaboration with Black architect Robert Taylor, Tuskegee University’s campus plan, and the campus plan for Howard University. Williston also designed Howard’s central gathering space, better known as “The Yard.”

(Photo by State Archives of North Carolina Raleigh, NC / No known copyright restrictions)

_800_492_80.jpg)

Within walking distance of Shaw University and St. Augustine’s College in Raleigh, North Carolina, "Negro Park" (today known as John Chavis Memorial Park) served as the green heart of Raleigh’s Black community. It was also a regional attraction and seen as one of the few “safe places” for Black people traveling between Atlanta and Washington, DC. The who’s who of Black political, economic, athletic, and entertainment leaders all frequented the park.

The park also supported political organizing. Shaw University is rightfully credited as the home of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a precedent for BLM, initially led by Ella Baker. South Park–East Raleigh residents alive at that time recall, however, that the initial planning and survival strategies employed in nonviolent direct action were rehearsed in the park. Specifically, the park was home to sessions training Black women to handle threats by aggressive white males in protest action.

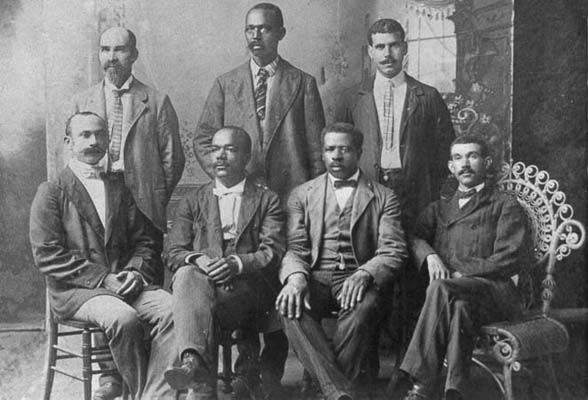

Some of the Founders of Mechanics & Farmers Bank; 1900. Durham County Library Archives

Around the same time as Tulsa's Black Wall Street was growing, in Durham, North Carolina, Parrish Street emerged as the home of what were two of the largest employers of Black Americans in history: North Carolina (NC) Mutual Life Insurance Company, and Mechanics and Farmers (M&F) Bank. At their heights, NC Mutual Life and M&F Bank funded and underwrote more Black land ownership and building construction than any other entities in the country. Their close proximity earned the area the moniker “Black Wall Street.”

Black Wall Street in Durham was located in the heart of downtown but was inextricably linked to the established Black community of Hayti, southeast of downtown.

(Photo by Valerie / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

On February 1, 1960, four Black students from North Carolina (NC) A&T State University occupied the lunch counter at Woolworth’s in downtown Greensboro, North Carolina. Their sit-in prefigured numerous similar activities across the South and is a key action that launched the modern civil rights movement.

The lunch counter eventually integrated, and that action provided a pathway for other college students to find roles in effecting social change. In Durham, students at an ice cream parlor staged a protest similar to the one at the lunch counter. Other protests involved streets. Although these public spaces were not “safe,” there was much less flagrant violence than was prevalent in the South at the time. The tenacity of Black students, coupled with hostile but largely nonviolent responses from whites, in part fed North Carolina’s past reputation as a moderate part of the South. That moniker no longer applies.

Still from the documentary Soul City

In 1969, in an unlikely political alliance, Floyd McKissick, the first Black graduate from UNC Chapel Hill’s law school, and longtime leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), worked together with President Richard Nixon to develop a “Black New Town” in Warren County, North Carolina.

Soul City was undermined by state and regional lack of cooperation, poor internal organization, and perceptions of impropriety. Homes were built prior to the installment of utilities. Commercial spaces were constructed without pro forma or business plans. Roads were disconnected and, in some cases, pushed to future phases, making the project inaccessible. In the end, the development was shut down partially finished, and it was subsequently used as a tool to discredit all involved.

(Continued on next slide)

Soul City entrance (public domain)

In the 1980s, North Carolina was planning to dispose of toxic chemicals in a new landfill in Warren County. As word spread of the proposed landfill siting, former civil rights–era activists, who had not worked since the 1950s and 1960s, and people who were involved in Soul City, mobilized. They deployed nonviolent direct-action tactics, derived from the civil rights movement, for environmental purposes. The protests garnered national attention, including that of academics who were beginning to correlate race and the siting of toxic waste facilities. Ben Chavis, the director of the United Church of Christ’s Commission on Racial Justice, was active in these protests.

The protests failed, and the landfill was built. However, Chavis’s 1987 report Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States was groundbreaking. The report stated that race was the primary determinant in the location of toxic waste facilities, outstripping income and other factors. The researchers said this constituted a pattern of “environmental racism.” In addition to the term and methodology, the Warren County protests were recognized as launching one of the first mainstream American environmental movements led by people of color.

(Public domain)

Generally, educational training in landscape architecture is devoid of the Black experience. Black educators represent less than 0.5 percent of all landscape architecture educators. Student enrollments have hovered at 1.5 to 2 percent for twenty years. Landscape architecture texts do not reference any contributions by Black landscape architects—no history, theories, case studies, or any other acknowledgments.

It is difficult to attract Black students to the profession when our profession offers little in the way of exposing them to Black professionals, projects, history, and theories that reflect them and who they are. As landscape architects, it seems disingenuous to work in Black communities without reflecting deeply on the disconnect between our professional desires and our professional composition. In the face of declining enrollments overall, we must reconsider how and why we teach the next generations about our profession.

(Photo by Oscar Perry Abello)

What if we told a different story about landscape architecture?

What if there were a People’s History of Landscape Architecture? Borrowing from Howard Zinn’s groundbreaking work A People’s History of the United States, what if landscape architecture were described with some acknowledgment of the dynamics of race, class, gender, and power? What if it were possible to see yourself in the mainstream of the profession even if you did not aspire to advanced white culture studies?

What if we told a different story?

How can we rethink our approaches so that Black Landscapes Matter?