Before and after photos of a recent renovation project on North Sarah Street in The Ville called St. Ferdinand II, sponsored by Northside Community Housing, Inc.

Photos Courtesy Northside Community Housing, Inc.

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberChuck Berry and Tina Turner. Dick Gregory and Robert Guillaume. Arthur Ashe. To Julia Allen, they are more than legends on the stage, on screen, on the tennis court or in the struggle for equal rights. At one point or another in their lives, they were her neighbors. Allen, 70, is a lifelong resident of The Ville, a historic African-American neighborhood in St. Louis.

“Our neighborhood is a small area in St. Louis but it really houses the majority of the black history of St. Louis because of segregation,” Allen says. “There’s so much history here that people don’t even know about.”

The Ville itself was a product of segregation. The neighborhood sits north of the “Delmar Divide,” referring to Delmar Boulevard as a dividing line running east to west across St. Louis City and County. In the early 20th century, as former enslaved persons and their descendants began to escape the Jim Crow south during the Great Migration, the white-controlled St. Louis real estate industry employed a system of racial covenants and steering to drive the city’s growing black population to neighborhoods north of Delmar, while driving white families to the south.

Black families made the best of the situation in St. Louis, rising to become lawyers, doctors, teachers, successful business owners and other professionals. Chuck Berry’s father was a contractor, his mother a school principal.

But the history of The Ville also includes the systematic denial of mortgages and other home-based lines of credit to black neighborhoods starting in the 1930s, known as “redlining.” Many left, including the black middle and upper classes, heading out to suburbs such as Ferguson and Kinloch, only for the cycle of mortgage denial to repeat itself.

“I’m 70, and this has been happening north of Delmar since before I was born,” says Allen. “Sometimes people want to stay in their homes, but because of redlining they can’t get the funds they need to maintain them over time.”

Today there are more than 800 vacant houses and 1,600 vacant lots in The Ville and surrounding Greater Ville neighborhoods — around 60 percent of properties in the area, including once-thriving commercial hubs and gathering places. Among the vacant houses is Chuck Berry’s former home, with the recording studio he added to the rear of the house. Beyond The Ville and Greater Ville, St. Louis is home to some 27,000 vacant buildings or lots, and they are heavily concentrated north of the Delmar Divide.

A new mortgage product, planning to roll out later this year, will be among the first of many steps toward undoing the generations of racist policies and practices that led to that level of vacancy — hypervacancy — in what was and in some ways still is a thriving black community. Called the Gateway Neighborhood Mortgage, it was inspired by a similar product in Detroit, a city facing comparable vacancy levels that took a similar approach.

Besides north St. Louis and most of Detroit outside of downtown, there’s Baltimore’s Black Butterfly, the South and West Sides of Chicago, Flint, the east side of Cleveland, the east side of Buffalo, large swaths of Indianapolis, Gary, even South Bend. Areas of vacancy or hypervacancy today were often the thriving black neighborhoods of yesterday. That’s not a coincidence. It’s by design.

“It’s part of that ingrained, invisible, institutionalized racism kind of thing that you don’t even know it’s there, but it’s there,” Allen says.

One new mortgage product alone won’t erase the effects of the institutional racism that spawned hypervacancy in the historically black neighborhoods of St. Louis. But the Gateway Neighborhood Mortgage is a microcosm of the multi-generational, multi-racial, multi-sector collaboration that has emerged over the past year to address vacant properties in St. Louis. To fully succeed will require additional resources and support from beyond the city itself, but for the first time — at least in Allen’s memory — there is a collaborative spirit around confronting the city’s scourge of vacant properties. Most importantly, that collaboration has deep roots in the experiences of longtime residents from the north side of St. Louis, such as Allen.

“I’ve been a resident of the Ville for 70 years, I’ve seen it when it was segregated and thriving, and now it’s more in transition,” Allen says. “For a neighborhood like ours to succeed and make the transition back to a viable community, we have to collaborate. In the city of St. Louis, that is a new idea.”

It would be easy to assume that nobody wants anything to do with the vacant properties on the north side of St. Louis, but Glenn Burleigh would beg to differ. As head of community outreach at the Metropolitan St. Louis Equal Housing and Opportunity Council, Burleigh spends much of his time attending community meetings north of the Delmar Divide to talk about the organization and its work as a bank watchdog group. In those discussions, he inevitably fields questions about obtaining mortgages. Around 2016, the questions started taking a particularly poignant turn.

“A lot of these people frankly felt hurt because they had gone through the entirety of homebuyer training programs that many nonprofits have, they had gotten their credit in shape, been pre-qualified for loans, and then they found it impossible to buy a house in their neighborhood,” Burleigh says. “The kind of situation I kept seeing was, ‘I saw this house, across the street from me, I could get it for $35,000, it needs about $45,000 in work, I was pre-approved for a $120,000 mortgage, but then the appraisal comes back and post-construction appraisal is not going to be high enough, so the loan doesn’t happen.’”

Many of The Ville's beautifully built, solid brick homes valued at just a few thousand dollars are structurally identical to those south of the Delmar Divide that are worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. (Photo by Paul Hohmann, CC BY-NC 2.0)

In fair housing and community development circles, this situation is known as the appraisal gap — when the cost of acquiring and renovating or rehabbing a property to make it usable is more than the home’s appraised value, even after the rehab. It’s a particularly insidious barrier. The bank doesn’t necessarily deny a mortgage application; it might even offer a mortgage, but just not a large enough mortgage to meet the buyer’s needs. So the application isn’t denied, but the applicant never takes out the loan. In official home lending data that lenders report to federal regulators under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act, these transactions do not appear, and it’s as if the application never existed. As the St. Louis Dispatch reported in 2018, all 11 areas of the city where no one applied for loans in 2015 and 2016 are north of Delmar Boulevard.

The appraisal gap is the result of a string of policy choices over the course of several decades. In 1916, St. Louis became the first city in the nation to pass a racial segregation ordinance by voter referendum. It was nullified the following year thanks to the Supreme Court case of Buchanan v. Warley, but St. Louis realtors and developers simply reverted to the use of steering and racial covenants to enforce the Delmar Divide.

In the mid-1930s, as part of FDR’s New Deal, the federal government began to subsidize and incentivize home mortgages in an attempt to kickstart the economy during the Great Depression. To guide the incentives, the federal government hired local squadrons of appraisers, brokers, realtors and other real estate professionals to designate areas as “best,” “still desirable,” “definitely declining,” or “hazardous.” The areas deemed hazardous were overlaid or outlined in red, giving rise to the term “redlining.” Despite the fact that The Ville and the rest of St. Louis north of the Delmar Divide were home to thriving communities, this area was redlined because it was also home to a predominantly black population.

Between 1934 and 1962, the Federal Housing Administration and later the Veterans Administration insured more than $120 billion in home mortgages, 98 percent of which went to white borrowers. For nonwhite populations, redlining starved neighborhoods of capital to make necessary repairs to their homes and other buildings over time. It also largely prevented the next generation of buyers from taking over when it was time for these owners to move on.

By the time the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968, which ostensibly ended redlining as an explicit federal policy, it was already too late for many of the homes and buildings north of St. Louis’ Delmar Divide. After decades of being denied the capital to keep homes in a livable state or to transfer them to a new generation of owners, many homeowners simply walked away, many to the suburbs. The city of St. Louis had a peak population of nearly 860,000 in the 1950s; today it’s just 319,000 — a steeper decline than in Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo, Pittsburgh, Flint, Dayton or any of the other former industrial powerhouses now known as “Legacy Cities.”

“It’s not a story that any of us here are proud of, but it is where we are today,” says Allan Ivie, president of community affairs and corporate banking for Simmons Bank in St. Louis.

The string of policies that ultimately resulted in hyper-vacancy continued after 1968. The deleterious effect of redlining was so pronounced in St. Louis that it became the first U.S. city to establish a city-run land bank, in 1971. The Land Reutilization Authority, or LRA, automatically assumes title over tax-foreclosed and other distressed properties that aren’t sold at sheriff’s auction. As people walked away from properties, they started to pile up in the LRA’s portfolio.

It gets worse. When St. Louis created the LRA, it decided that rather than allocating funding out of the city’s general budget revenue, it would primarily receive funds from the sales of its properties along with a few federal grants from the Department of Housing and Urban Development. That was intended to provide an incentive to sell homes more quickly back into the private market, but the assumption was that banks would be willing to make purchase and rehab loans of sufficient scale to borrowers.

Given the long history of segregation and redlining, it’s been ages since neighborhoods with a high concentration of LRA properties have seen even a small amount of mortgage activity. Appraisers already had trouble calculating valuations that would cover what potential homeowners needed to acquire and sufficiently rehab homes in the LRA’s portfolio — and the LRA typically requires purchasers to show they already have the financing to rehab homes before accepting a purchase offer.

With sales of its properties chronically slow and no general funding from the city, the LRA has consistently struggled to finance maintenance and upkeep for properties in its portfolio. So the properties keep spiraling into ruin. Dilapidated homes became magnets for crime and eyesores across entire neighborhoods, giving appraisers further reason to devalue nearby properties. All the more reason for residents north of the Delmar Divide to walk away.

“In our inventory, it’s typical to find houses with no water, no roof, no back wall, no sewer, no services, everything’s been stripped, it’s partially collapsed,” says Laura Costello, who has been running the LRA since 2006.

Today the LRA’s portfolio numbers around 12,000 properties, some acquired as far back as the mid-1980s, and they remain heavily concentrated north of the Delmar Divide. On many blocks, Costello says, the LRA owns a majority of the homes. Up until 2010, the LRA had an active strategy that once the agency owned 80 percent of the homes on a block, it would go out and purchase the remaining homes just to give a developer the chance to buy the whole block at once if they wanted.

Allen once considered taking on a second property to renovate and sell, but was discouraged when she heard, “you might get the money, but then when you go to market if you want to sell the property you won’t get the full value of what you need to get that back.”

Take a drive through north St. Louis, or even scour the LRA’s online property database, and it’s obvious (even without knowing the history) why residents still have a strong desire to acquire and rehabilitate the houses around them or to rebuild what’s already been lost. Look past the overgrown grass and boarded up windows and find many beautifully built, solid brick homes, many of them in the Victorian style of the late 19th century. Many homes north of the Delmar Divide that are valued at $2,000 are structurally identical to those south of the divide that are worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

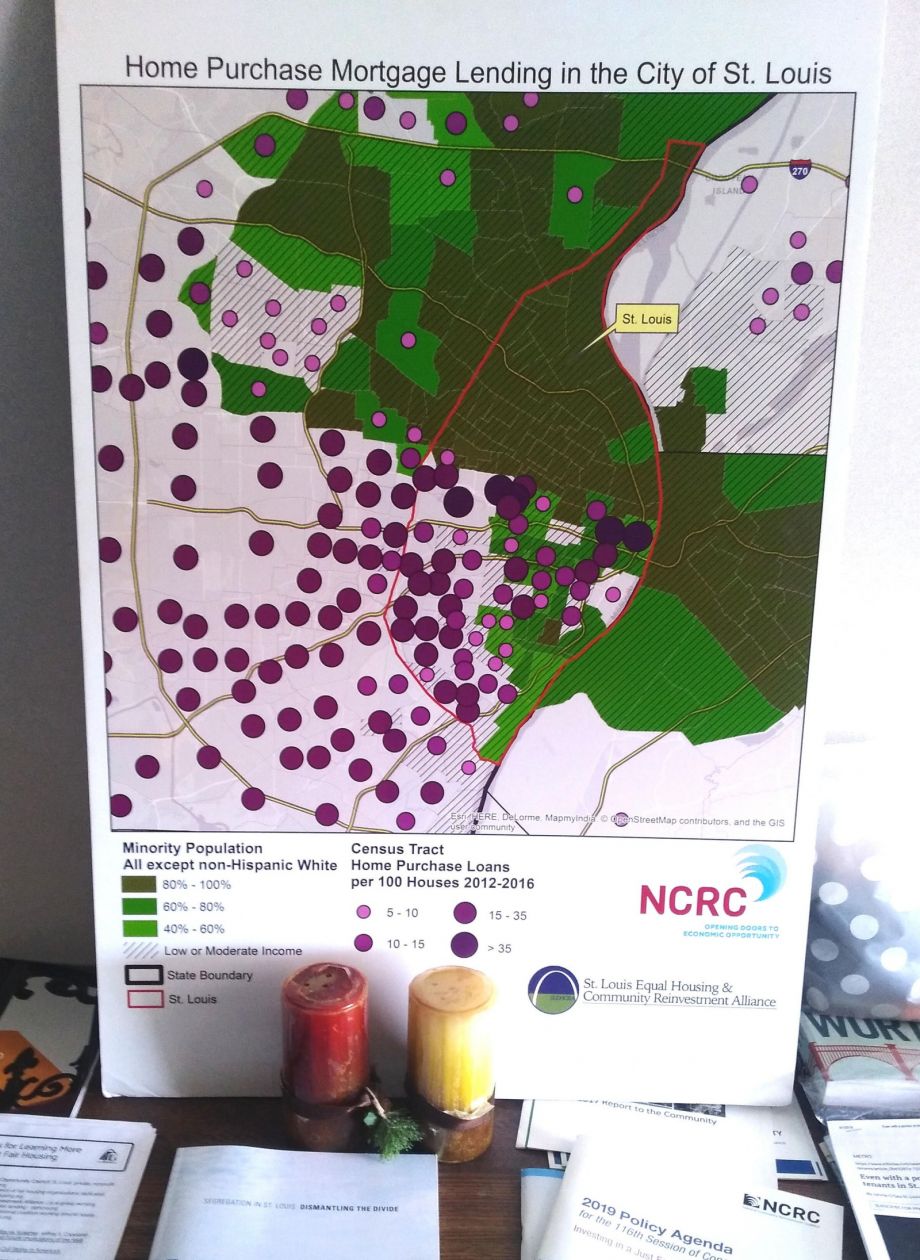

In July 2016, the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, a national coalition of bank watchdog and community development groups, put out a report analyzing home lending in St. Louis, Milwaukee and Minneapolis. In its analysis of St. Louis, the coalition found that having a higher proportion of African-American residents within a census tract correlated with fewer mortgage loan originations. Using data from 2012 to 2014, the report included a map of mortgage lending by census tract in St. Louis, overlayed with racial demographics, showing the stark absence of mortgage lending north of the Delmar Divide.

Burleigh printed out a blown-up version of that map, put it on poster board, and started bringing it to every meeting he went to, using it to spark discussions about the appraisal gap. He wanted everyone else to see beyond just the banks or just the real estate industry or the land bank or the city or the homeowners who had walked away after decades of being denied access to capital — everyone had inherited a system built over the course of multiple generations that still produced racist outcomes, whether anyone involved today intended to be racist or not.

The map that Glenn Burleigh carried from meeting to meeting, showing the stark lack of mortgages granted to residents north of the Delmar Divide. (Photo by Glenn Burleigh)

“When I was dragging that map around, explaining the appraisal gap, one thing I stressed repeatedly was that this is a situation today where not a single racist decision has to be made to shut down these loans,” Burleigh says. “[Because] it is a racist system.”

Even white borrowers who may want to buy north of Delmar face the appraisal gap because the appraisals are tied to recent property transactions near the property they intended to purchase. So if publicly available records show that the only recent transactions nearby have been all-cash purchases from the LRA for just a few thousand dollars each, that’s what appraisers will use in their calculations.

It became impossible to ignore the message, even for banks in St. Louis. “We’re not saying that you don’t run into credit issues in these areas,” says Ivie. “But what we’re talking about here is not a credit issue or an income issue, it’s an appraisal issue.”

In late 2017, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) organized a discussion in St. Louis, bringing in representatives from Baltimore, Memphis and Detroit, to share what they were doing in those cities to increase home lending in historically redlined neighborhoods. Burleigh was there, representing his organization as well as the St. Louis Equal Housing and Community Reinvestment Alliance (SLEHCRA), a broader coalition of nonprofit and community organizations.

“That meeting was important for us because it wasn’t SLEHCRA saying something like this needs to happen, it was the FDIC saying something like this needs to happen,” Burleigh says.

That meeting planted the seed for what became the Gateway Neighborhood Mortgage program. It’s modeled directly on the Detroit Home Mortgage program, which was presented at that meeting as a way of working around the appraisal gap. Burleigh went back with his colleagues and started promoting the idea of doing something similar in St. Louis.

It turns out Burleigh wasn’t the only one in that meeting who felt so inspired — a few bankers at the meeting took the same message to heart, and went back to their colleagues and started working up their own proposal for a program modeled on Detroit Home Mortgage. The bankers were part of the Metropolitan St. Louis Community Reinvestment Association (MSLCRA), a banking industry group. One of those bankers emailed Burleigh in March 2018 to see if he was interested in talking with them about it.

“Well, I actually just left a meeting with some of the mayor’s staff about this exact topic,” Burleigh wrote back. “[My colleague and I] were just talking about when we thought we could potentially set something up with MSLCRA, too. So you’re basically psychic.”

The bankers and the bank watchdog groups began working side-by-side on what was initially dubbed the “Greenlining Fund.” The idea made it into “Dismantling the Divide,” a major report from a research team based at Washington University in St. Louis, published in June 2018. And it made it into Mayor Lyda Krewson’s “Plan To Reduce Vacant Lots and Buildings,” unveiled in July 2018 after a year-long public drafting process.

“The term ‘greenlining’ we didn’t just pull out the air,” says Clayton Evans, who was at that FDIC meeting as senior vice president and community affairs officer at Simmons Bank. “It had real meaning. It’s placing dollars in those areas that have been redlined in the past.”

Based on the Detroit Home Mortgage program, the Gateway Neighborhood Mortgage will work by combining a first and a second mortgage into one transaction. The first mortgage will be an appraisal-based mortgage, covering up to 97 percent of the home’s appraised value, with the borrower covering the remaining three percent with their own funds along with any down payment assistance for which they might be eligible from the city or other programs. The second mortgage covers the appraisal gap, up to $75,000.

As in Detroit, a set of banks will provide the first mortgages on a rotating basis — Carrollton Bank, Central Bank, Enterprise Bank & Trust, Great Southern Bank and Simmons Bank. The second mortgages will come from a $2-million loan pool managed by a federally-certified community development financial institution (CDFI) — an organization that specializes in providing responsible loans and other financial services to low- and moderate-income borrowers. In St. Louis, the CDFI will be Justine Petersen. Based north of the Delmar Divide, Justine Petersen started off as a housing counseling agency 20 years ago, but today is more known for its small-business lending — and the vast majority of its clients in St. Louis are north of the Delmar Divide.

The Gateway Neighborhood Mortgage will require a minimum credit score of 620 — if there are any interested potential homeowners with lower credit scores, one of Justine Petersen’s other specialties as a CDFI has been providing credit building loans and counseling.

“The Gateway Neighborhood Mortgage in and of itself is something amazing, but it’s also amazingly symbolic of where we are in our CRA [Community Reinvestment Act] movement, and I want to call it a movement here in St. Louis,” says Galen Gondolfi, senior loan counselor and chief communications officer for Justine Petersen.

In contrast with Detroit, the banks will service both loans, meaning borrowers will only need to make one monthly payment to the bank instead of one to the bank and one to the CDFI.

Within the current system, appraisals are tied to recent property transactions near the property they intended to purchase. So if publicly available records show that the only recent transactions nearby have been all-cash purchases from the LRA for just a few thousand dollars each, that’s what appraisers will use in their calculations, and a buyer won't get approved for a mortgage large enough to cover the purchase and the rehab. (Photo by Joe Rakers)

The funds for the second mortgage loan pool will come from multiple sources, including long-term loans from banks or grants if possible. Simmons Bank was one of the early investors, chalking up a $500,000 investment for the loan pool — banks making mortgages or investments into the loan pool can get credit for doing either from federal regulators on their regular Community Reinvestment Act examinations. The city also provided a $100,000 investment for the loan pool. The groups behind the Gateway Neighborhood Mortgage had hoped to launch it by this summer, but raising capital for the second mortgage pool has proven more difficult than anticipated. They’re hoping to launch by the end of 2019.

In the meantime, the banks involved also have work to do, educating their own mortgage lending teams about the product, as well as reaching out to those who will help them connect with buyers — first and foremost, St. Louis’ neighborhood associations, but also the local aldermen, the few surviving local businesses in the neighborhoods, even alumni of Sumner High School, which counts Chuck Berry, Tina Turner, Dick Gregory, Robert Guillaume and Arthur Ashe among its illustrious graduates.

Neighborhood associations will play an essential role in spreading the word about Gateway Neighborhood Mortgage. These are neighborhood-based organizations in St. Louis that residents start and run, primarily on a volunteer basis, to coordinate clean up work or block parties or other events that foster a sense of community within a specific area. They also play a role in advocating for policies and programs to meet members’ needs. Many of the associations were organizing around reducing vacant homes and properties before anyone else. It was mostly their regular meetings where Burleigh heard from members about running into the appraisal gap.

In order for the Gateway Neighborhood Mortgage to live up to its potential, it needs to connect with a handful of buyers interested in the same neighborhood at around the same time, creating a set of recent mortgage transactions for appraisers to reference the next time someone wants a mortgage in that neighborhood. Lenders would then be able to make subsequent appraisal-based loans at values that meet the cost of rehab, and the product wouldn’t be needed in that particular neighborhood any longer. The program will target five initial neighborhoods, four of them north of the Delmar Divide, and once the gap is closed it will move onto other neighborhoods until the gap is closed across all of north St. Louis. If it works as well as they hope, the partners behind the mortgage plan to eventually expand the product to the county, and across the Mississippi to the east.

“You can’t quantify if you need five or ten Gateway Neighborhood Mortgage loans to close the appraisal gap, but once we have a few initial loan closings under our belt, we probably won’t need more than ten within a neighborhood,” says Ivie.

By closing the appraisal gap, the loans clear a path for other borrowers to access conventional mortgages. From 2016-2018, Detroit Home Mortgage made 228 total loans, just eight percent of all home mortgages made in Detroit over that time frame, and mortgage lending finally returned to pre-Great Recession levels in 2018.

“The way I personally look at it is, we are generating demand and building community power at the same time, those two things have to be in sync,” Williams says. “When The Ville’s market does become attractive, the community’s voice should be powerful enough to dictate what would be here.”

The Gateway Neighborhood Mortgage is a bit less ambitious, planning to make 60 loans over its first three years.

“Now it’s about attempting to drill down to identify what the potential homebuyer looks like,” says Evans. “Is it going to be a homebuyer that has some history in the community, may have been raised in the community, may have relatives nearby and a desire to move back into the city of St. Louis from the county? Is it a potential homebuyer who owns or works at a business in the area?”

August 2019 marks five years since the killing of Michael Brown, an unarmed black teen, at the hands of police officer Darren Wilson in the St. Louis suburb of Ferguson, Missouri. As researcher Richard Rothstein once argued, it was the suburban replication of segregation and systematic neglect of black neighborhoods that created the conditions for the distrust and over-policing of black people that resulted in Brown’s death.

Brown’s killing and the subsequent uprisings in response to his death galvanized a regional examination of those conditions, encapsulated in the Ferguson Commission and its landmark report. For the St. Louis neighborhood associations, that broader examination coincided with a decision to make reducing vacant properties a collective priority, starting in 2015.

“We are post-Ferguson, so everyone now has racial equity lenses, and that’s a good thing, and we have to take advantage of that and recognize that vacancy disproportionately affects communities of color in St. Louis, predominantly north St. Louis,” says Sundy Whiteside, the current board president of the St. Louis Association of Community Organizations, known as SLACO, the umbrella group for neighborhood associations in St. Louis.

Whiteside ran for SLACO board president last year with the intention of spending her term focused on reducing vacancy. She’s since become the co-chair of the Vacancy Advisory Committee of the Vacancy Collaborative, a public-private collaboration that launched last year to help coordinate all the emerging work around reducing vacancy in St. Louis.

“We’ve felt a lot of the decisions made around development and the vacancy problem were made in a vacuum that did not include us as residents, that we didn’t have a voice,” Whiteside says.

The Gateway Neighborhood Mortgage is just one of many planned initiatives to come out of Vacancy Collaborative members working across sectors.

“My vision is to keep pushing for this to become a movement,” Whiteside says. “I will be pushing more community engagement, especially in the areas most impacted by vacancy. Every member that we bring to the table to participate in the collaborative, they talk about how much hope they have.”

That hope is also present in The Ville, which currently does not have an official neighborhood organization under SLACO — but it does have something else.

In 2016, Allen met another lifelong Ville resident, Thomasina Clarke, through the Place-Based Community Arts Training (CAT) Institute, a program of the Regional Arts Commission — a quasi-public agency that gets most of its funding from hotel/motel room sales taxes in St. Louis City and County. Allen and Clarke teamed up with Aaron Williams, a transplant to St. Louis from Kansas City, to become founding members of 4theVille, a group of multi-generational Ville residents and volunteers that uses interactive storytelling methods to share the history of the neighborhood.

4theVille’s first initiative: a citywide call for artists to create two billboards celebrating the history and legacy of the Ville and its residents. The billboards went up in 2018, featuring Chuck Berry, Tina Turner, Dick Gregory, Annie Malone, Grace Bumbry, Homer G. Phillips and Wendell Pruitt. This year they partnered with St. Louis REALTORS, Rebuilding Together and Northside Community Housing to commission a commemorative poster for the 50th Anniversary of the Fair Housing Act and the 70th anniversary of Shelley v. Kraemer — the Supreme Court case that ruled states could not enforce racial covenants, which centered on a house located in The Greater Ville.

Williams also co-founded the Northside Trap Run, a hip-hop themed 1-mile walk/5k run through the streets of The Ville, with DJs set up every half kilometer along the course. More than 300 walkers/runners participated in the inaugural event last year.

“They get to listen to DJs and they get to see the whole story of the community, to see some of the things we’ve achieved but also the buildings that are still crumbling and they’re forced to grapple with that,” Williams says.

The long-term vision for the Northside Trap Run and 4theVille is to inspire new and invigorated ownership of the community. The organizers behind each want to spark interest in the 800 vacant houses and 1,600 vacant lots from potential buyers who value the neighborhood’s history and maybe have some prior connection to it — buyers who want to add to the power of the existing residents who have stuck it out all these years. Closing the appraisal gap in north St. Louis would remove one key barrier for those potential buyers.

“The way I personally look at it is, we are generating demand and building community power at the same time, those two things have to be in sync,” Williams says. “When The Ville’s market does become attractive, the community’s voice should be powerful enough to dictate what would be here.”

The Gateway Neighborhood Mortgage is just one early step toward resolving the interconnected issues of vacancy, segregation and inequality in St. Louis. But it is important to recognize that it represents a direct response to the fact that there are many who still live on the north side of St. Louis — or have some meaningful ties to it — who believe enough in those neighborhoods to want to invest in them.

The problem for people in that situation isn’t a lack of capital. There are $28 billion deposited in bank branches within the city of St. Louis and the Community Reinvestment Act says “regulated financial institutions have [a] continuing and affirmative obligation to help meet the credit needs of the local communities in which they are chartered.” The problem is the appraisal gap — and it’s also important to recognize the collaboration it took to finally create a way to get around it.

“One of the key positive things with this effort is it provides the chance for banks to work in a collaborative manner with each other and with nonprofits and with government,” says Ivie. “Usually as bankers, we’re competing with each other hand over fist all over the place.”

The Northside Trap Run, which takes participants through The Ville. (Photo by Joe Rakers)

But St. Louis needs much more than the Gateway Neighborhood Mortgage at this point to make real progress in reducing vacant buildings and lots and getting them back on the tax rolls. Many of the properties in the LRA’s portfolio are in such a state of disrepair that Costello isn’t sure that closing the appraisal gap will provide access to enough capital to bring those properties back into service.

Some help recently came for the LRA, in the form of a ballot initiative that created a tiny increase in property taxes to finance an estimated $6 million a year in funding for the LRA to perform some of the deferred maintenance and modernization needed for the 3,400 vacant homes in its portfolio. It’s helpful, but even that isn’t enough to meet the scale of the challenge.

“The city has long faced a situation of only having a water gun to put out a raging vacancy inferno,” says Burleigh. “The amount of deferred maintenance that has accrued is far beyond the means of funding via any local tax levy. Any real solution to such a widespread phenomenon would certainly have to be federal.”

There are new proposals floating around the 2020 Presidential campaign trail, such as the 21st Century Homestead Act, which would, among other components, create a new federal funding source for land banks across the country to rehab properties in their portfolios before transferring them back to private ownership. The proposal was authored by author and law professor Mehrsa Baradaran.

“St. Louis is a prime place to test if this 21st Century Homestead Act can work,” Baradaran says.

It took very intentional practices in the private sector and at multiple levels of government to create today’s quandary of hypervacancy in historically African-American legacy city neighborhoods. It makes sense that likewise, it would take coordination at multiple levels of government and very intentional private-sector practices to find a way out of it. It also took a long time to get into this quandary — more than one or two election cycles, more than one or two grant cycles, more than one or two generations. With any luck, it will take a generation or less to get out.

“I think some people fail to realize that if you’re about accountability and moving together, you also have to be about moving at the speed of trust,” Williams says. “That means moving at the speed of the most untrusting person in the room.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story has been amended to correct the spelling of Allan Ivie’s first name.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine