Natalie Gunn is the chief financial officer at Capital Impact Partners, a community development loan fund with a nationwide footprint in the U.S. and a $311-million loan portfolio. In any given month, she sees a handful of new deals come across her desk, financing anything from federally qualified health centers to charter schools, or mixed-use projects with low- or middle- income housing, or a community-owned grocery store in an area that qualifies as a food desert. Some months may see no deals. December is often busy — “Ten deals is extreme,” she says.

Gunn’s job is to connect those deals to all the different sources of capital that her organization can access — including large banks, smaller banks, foundations, federal or state or local governments, or big-money managers such as those who manage 401ks, individual retirement accounts and pension funds. Capital Impact Partners has raised $100 million from those big-money managers over the past year. But in some months, the fund may experience more deal flow than cash on hand at that moment. Some investors may restrict their cash to specific geographies that don’t overlap with this month’s deals. In financial institution parlance, this is when the fund needs “liquidity.”

One solution for liquidity is old, yet still surprising; often mundane but still exciting, especially if you’re thinking about how to fund more affordable housing, or creating jobs with benefits that pay a living wage, or even financing the Green New Deal. It’s called the Federal Home Loan Bank system, created by an act of Congress in 1932 to help kickstart home lending in the midst of the Great Depression. Over the past few years, an increasing number of community development loan funds such as Capital Impact Partners have turned to the Federal Home Loan Banks to meet their liquidity needs.

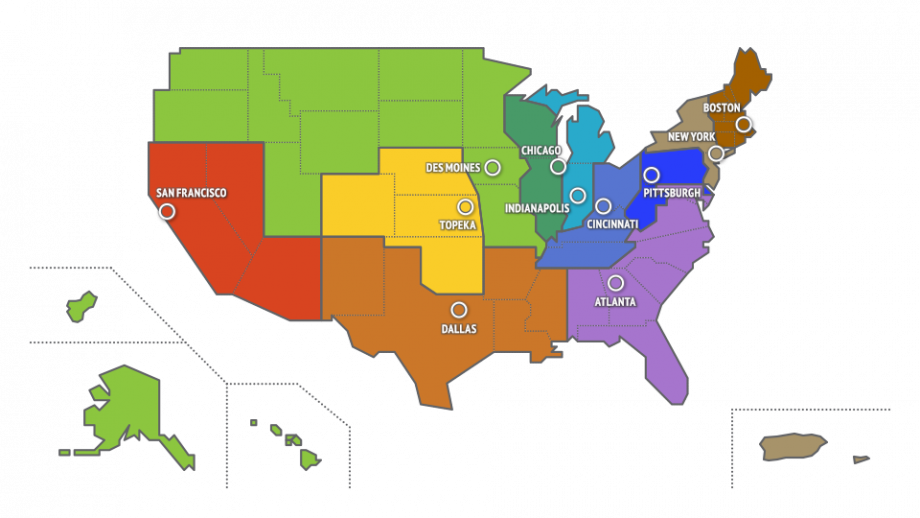

One of the early proposals from Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) made reference to a “system of regional and specialized public banks” that would be necessary to finance parts of the Green New Deal agenda. She may or may not have had them in mind, but the Federal Home Loan Bank system consists of eleven cooperatively-owned regional banks. Collectively, they represent the oldest and largest government-sponsored enterprises in the country, with a trillion dollars in assets, and while they have the intrinsic backing of the U.S. Government, they operate with zero taxpayer dollars. They might be the best-kept secret of the U.S. financial system.

The eleven Federal Home Loan Banks are bank’s banks. They don’t take deposits; instead, they borrow from global capital markets — and very cheaply, since they have the implicit backing of the U.S. Government. Then they turn around and primarily make loans to their members, who are also their shareholders. Loans to members can be for one day or for up to 20 years, and the funds can be wired into members’ accounts in less than an hour.

Over the past few decades, often in the aftermath of a financial crisis, Congress has incrementally expanded the Federal Home Loan Banks’ mission beyond exclusive support for home lending and expanded their eligible membership base of banks and savings and loan associations. Credit unions became eligible in 1989. Insurance companies started becoming members in 1992, in the aftermath of the savings and loan association crisis that wiped out many Federal Home Loan Bank members. Community development loan funds such as Capital Impact Partners became eligible for membership under the Housing and Economic Recovery Act, passed after the 2008-2009 subprime mortgage crisis.

According to their most recent aggregated financial report, there are around 7,000 Federal Home Loan Bank members across the United States. About two-thirds of them are banks, along with 1,479 credit unions, 704 savings institutions, 426 insurance companies, and 55 community development loan funds — up from 26 community development loan fund members in 2014. To be eligible for membership, community development loan funds must first have federal certification as a community development financial institution (CDFI).

Since becoming a member of the Federal Home Loan Bank of Atlanta in 2015, Capital Impact Partners has borrowed $20 million in advances from the bank, with about $11 million currently outstanding. According to the Federal Home Loan Bank of Atlanta, over the past few years, their eight CDFI members, as a group, have typically hovered between $25 and $40 million in advances outstanding, in any given month.

“CDFIs play an enormously important role in community investment, which is central for the Home Loan Banks’ long-established mission,” says David Jeffers, executive vice president at the Council of Federal Home Loan Banks, a hub organization in Washington, D.C., which coordinates on legislative and regulatory issues and public affairs for the Federal Home Loan Bank system. “The outreach to CDFIs has been a two-way street. We’ve been working together to understand each other’s business, and the growth in CDFI membership numbers reflects that fact that the dialogue has been robust and positive.”

There are some key constraints on Federal Home Loan Bank membership and borrowing that make it challenging for smaller institutions to work with them. For one thing, all members have a borrowing limit based on the size of the institution. Since larger members have higher borrowing limits, they typically account for the lion’s share of Federal Home Loan Bank lending — a point of criticism for some. Members also have to make an initial purchase of shares and must purchase additional shares with each advance they take out. And they must pledge a certain dollar amount of collateral for every dollar they borrow.

While it’s too early for anyone Next City interviewed to say explicitly that Federal Home Loan Banks can and will play a role in financing a Green New Deal, the pervasive role they play in the financial system makes it hard to imagine they won’t somehow be involved, at least indirectly.

The expansion and growing activity of CDFI membership among Federal Home Loan Banks hint at what could someday become a direct or explicit source of financing for activities that fall under the umbrella of a Green New Deal. Many of the 1,100 CDFIs across the country are already financing projects along the lines of environmentally sustainable construction or retrofitting older buildings for sustainability, or financing clean energy businesses that offer living-wage jobs.

Another available tool could be expanding the Federal Home Loan Bank’s grant programs, such as the systemwide Affordable Housing Program, or the Federal Home Loan Bank of Chicago’s Community First Fund (previously covered by Next City), or the Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco’s Quality Jobs Fund (also covered by Next City). These focused grant programs are funded out of the net earnings of Federal Home Loan Banks — no big federal budget battles required.

In the most recent quarterly report available from the Federal Home Loan Bank system, 24 total CDFIs across the country had taken out $206 million in advances, up from $162 million at the end of 2017. That may be a negligible percentage of the system’s $1 trillion in assets, but it’s a significant sum to Capital Impact Partners and other CDFIs who have started to figure out the different ways it can grease the wheels of investing in historically dis-invested areas and in projects that have a focus on environmental sustainability.

“It’s really flexible, and it allows us to be flexible in lending,” says Gunn.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)