It was November of 2016 when Tim Moreland traveled to Denver for a week-long training in the city’s “Peak Academy,” a program that’s meant to empower city employees to create and implement their own improvements to the way their government works. Moreland, the director of performance management and open data for the city of Chattanooga, Tennessee, was there as both a participant and observer. The experience convinced him that the program could work in Chattanooga, too. So three months later, with no budget and no staff, Moreland helped Chattanooga launch a Peak Academy of its own.

In the ten months since then, more than 100 city employees have gone through the training program. They’ve come up with dozens of micro-innovations to make government work more efficiently, from cutting down on the use of paper and ink to experimenting with new recruiting practices to help diversify the city’s police force. Because it’s run by volunteers who work on the program in addition to their “regular” jobs, Peak Academy doesn’t cost the city anything. In fact, it’s actually begun to generate a small amount of revenue, as outside organizations, including the United Way of Greater Chattanooga and the Tennessee Valley Authority, have paid the city to send their own employees to the program.

In concept, Peak Academy is aligned with ideas of “lean” processing and continuous improvement that are popular in the corporate world. The goal, says Michael Baskin, chief policy officer for Chattanooga Mayor Andy Berke, is to give city workers the tools they need to address issues that they’ve identified in their daily work. Instead of setting specific goals and expecting specific outcomes, the program is meant to help employees design and implement better practices on their own.

“Peak Academy is one strategy that my administration has used to help our staff realize their full potential as public servants,” said Berke, in a statement emailed to Next City. “Through their work in Peak, we can discover new efficiencies and entirely new approaches to existing challenges, both big and small. The return for the citizens of Chattanooga is more and better services at lower cost, which allows us to invest more resources in other ways.”

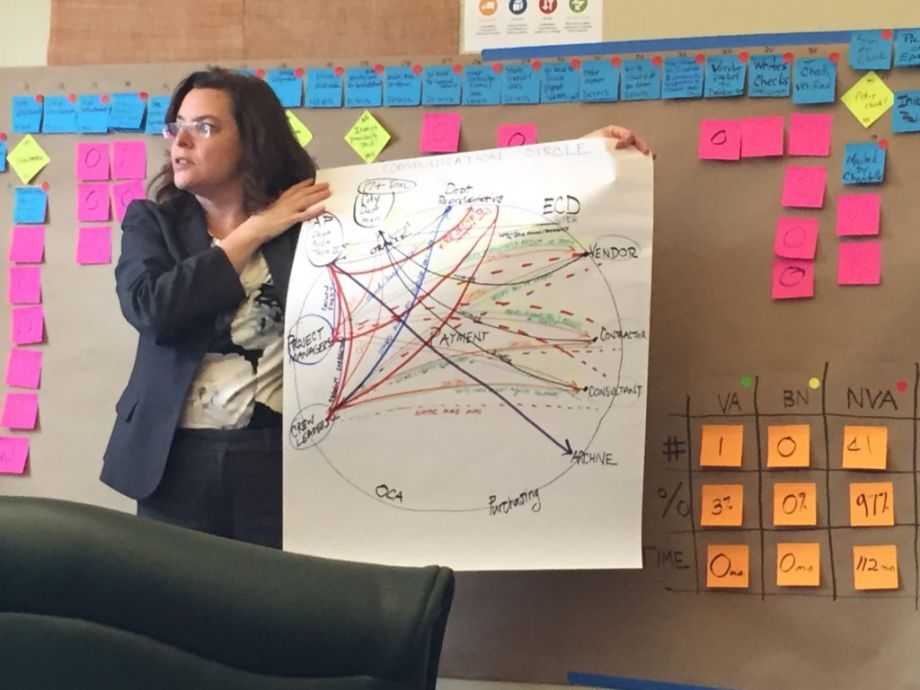

The Peak Academy has two levels: “Green belt,” which involves less than a day of training, and “black belt,” which lasts for a week. Baskin says that in the black belt trainings, the first two days are spent helping employees identify and understand problems. Workers often come in wanting to jump straight to solutions, Baskin says, but the structure of the training encourages them to think first about “what the customer wants.” They start talking about solutions on the third day. At the end of the week, trainees are expected to present to their managers and peers three improvements that they plan to make—again with no new budget, staff, or technology.

“We work with people who want to work with us,” says Moreland. “It’s done purposefully so we get people who are excited and engaged.”

Moreland says that Peak Academy participants have so far identified 206 potential innovations and carried out 22 of them. They’ve already saved the city $85,000, he says. One employee had been routinely printing out eleven copies of major government contracts, all for internal use in various departments. Most of the time the full contracts weren’t needed, she realized, so she started only printing them out on request. After a library worker and a coordinator of the police force’s gang unit went through Peak Academy together, they decided to create a collaborative reading club between the two departments, with the aim of increasing empathy among the police force.

“It gives people a common language that allows them to create change together,” says Baskin.

Another employee simply reoriented her desk space so that she was as easily accessible to members of the public as she was to her co-workers. If everyone in city government tried to make small improvements in their work systems every day, Baskin says, the cumulative effect would be powerful. In many instances, employees are finding ways to cut out superfluous tasks that aren’t key to their actual jobs.

In Denver, Peak Academy innovations have allowed the city to reduce its average recruitment and hiring time by 20 days, from a baseline of 84 days. Denver’s program inspired a similar academy in San Diego, called OpEx, for “operational excellence.” San Diego’s performance and analytics department studied employees’ processes and found ways to replace street lights more quickly and shorten the time it takes to answer 911 calls, according to The San Diego Union-Tribune.

According to Baskin, the academy has charged non-city employees between $500 and $2,000 to participate in the weeklong training sessions. It’s been so successful that one county government in bordering Georgia has come knocking, and is thinking about creating a Peak Academy of its own, Baskin says. Money aside, Baskin says, the program is helping city employees do their work in ways that make more sense to them, and that’s good for morale.

“Sure there’s some hard dollar savings,” Baskin says, “but it’s really about freeing someone up.”

Jared Brey is Next City's housing correspondent, based in Philadelphia. He is a former staff writer at Philadelphia magazine and PlanPhilly, and his work has appeared in Columbia Journalism Review, Landscape Architecture Magazine, U.S. News & World Report, Philadelphia Weekly, and other publications.

Follow Jared .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)