About a week before college classes began in Boulder, Colorado, in 2016, hundreds of students and other tenants moved into their apartments and discovered two people would be living in each bedroom.

After complaints to the city, Boulder housing officials stepped in, finding the owner had illegally subdivided the rooms and that some units lacked smoke alarms and fire exits.

Officials emptied the building and crews were immediately on site making repairs. The next day, students began returning to their apartments. Within a month, the city had cited the property owner with 184 counts of building violations. By December, the landlord agreed to a $410,000 settlement, local media reported.

Housing experts have held up Boulder as a model for how cities can help protect tenants. The college town began registering landlords in the 1970s in an effort to regulate the quality of homes being rented to students. Five decades later, the system has been credited with preventing unsafe conditions and acting quickly to address problems.

In Chicago, the buildings department moves more slowly.

In August of this year, about 20 tenants of the Edison Apartments in Edgewater rallied outside the 100-year-old building to get the attention of their landlord — or the city — to improve living conditions.

Jorge Iván Soto, 26, moved in last November and said water dripped from the ceiling and seeped from the floor during his first rain storm in the apartment. Then earlier this year, chunks of paint and drywall fell onto his bed, forcing him to spend two nights in a hotel, he said.

Soto soon realized he wasn’t alone. Other tenants in the building shared stories of leaky pipes, warped floorboards, rat infestations and more, he said.

Residents of the Edison filed 84 unique complaints to the city’s buildings department between January 2020 and July 2023, according to city 311 records. City inspectors visited the property four times during that period — twice they were denied entry and twice they logged multiple violations against the owner with no clear result, according to records from the buildings department.

A judge ordered the building into receivership in late 2022, and California-based Trigild Inc. took over as property manager. In an email to Illinois Answers, a representative for Trigild said its management team has met twice with tenants to remedy issues.

Advocates at the nonprofit Metropolitan Tenants Organization, who helped Edison residents organize into a tenants’ union, say inaction from Chicago building officials and lack of communication from the landlord are symptoms of a haphazard, reactive set of safety regulations that leave tenants in danger.

“If we had a consistent cycle of building inspections and mandates for upkeep, buildings would not fall into the state of disrepair I found when I first moved in,” said Ben Payne, who moved into the Edison late last year and spoke at the rally in August.

Tenants and their advocates point to a measure sitting in a City Council committee as a potential solution: the Chicago Healthy Homes Ordinance, which would pave the way for the city to track apartment landlords and conduct periodic safety checks.

How can Chicago address building safety reform?

Advocates have long called on Chicago’s buildings department to ramp up inspections and modernize its data reporting.

The city’s building code used to require that every multifamily residential building three stories or taller be inspected annually, but the City Council scrapped the requirement in 2017 at the behest of then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel.

Under the existing system, building inspectors are assigned stacks of complaints every day and told to follow up on as many properties as time permits. Several dozen inspectors were tasked with responding to more than 56,000 building-related complaints to 311 across the city in 2022, according to city records.

Chicago requires some annual checks for high-rise apartment buildings that are more than 80 feet tall, like the Edison, but those inspections are limited in scope and mostly pertain to fire safety conditions like sprinklers and emergency exit paths. The city has no policy of proactive inspections for other residential buildings.

City buildings officials have defended that complaint-driven process, saying it directs them to the properties needing the most attention.

But a 2021 investigation by the Better Government Association — the publisher of the Illinois Answers Project — and the Chicago Tribune found dozens of examples in which Chicagoans died in fires inside buildings that city officials knew were unsafe but never addressed. A followup investigation this year found that the problem persists and that patchwork regulations since put into place have done little to fix the system’s underlying issues.

Former Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot dismissed the findings of the Pulitzer Prize-winning “Failures Before the Fires” series.

As a candidate, Mayor Brandon Johnson expressed openness to reforms, telling Illinois Answers in March that the city should invest in inspections and proactively enforce safety codes. However, the 223-page report released by Johnson’s transition team in July didn’t mention building safety problems.

In a statement this month, Johnson spokesperson Hannah Fierle said the administration “agrees with the values and spirit of the Healthy Homes Ordinance,” which would launch a pilot inspection program in a handful of city wards.

“We look forward to working with advocates and all the agencies involved to grapple with the policy design in the future to accomplish those goals,” Fierle said. “As always, we center those most immediately impacted.”

With the mayor’s attention spread thin, prospects for building safety reform in Chicago may depend on how much pressure comes from advocacy groups and City Council.

Ald. Rossana Rodriguez-Sanchez (33rd) called the Healthy Homes Ordinance a priority for the Committee on Health and Human Relations, which she chairs, but she hasn’t yet called a meeting to discuss it. The alderwoman told Illinois Answers the initiative has so far been sidelined by other legislative efforts, but she reiterated that she plans to push the initiative later during Johnson’s term.

As proposed, under the Healthy Homes Ordinance:

- A rental unit registry would be created to track building ownership and identify owners who have violations across multiple buildings.

- Every apartment building would be inspected at least every five years for safety problems like mold, missing smoke detectors, lead paint or pest infestations.

- Landlords would face repercussions depending on whether each violation is deemed life-threatening, serious, or minor.

- Tenants would be notified of the inspection 30 days beforehand and would be given an opportunity to speak directly with the inspector or submit comments.

- Each safety violation would prompt a remediation order setting a deadline for when problems need to be fixed.

- For life-threatening violations that require tenants to relocate, the landlord would be required to pay their moving costs.

- The checks would be conducted by a new team of building inspectors housed under the Chicago Department of Public Health.

The three-year pilot program would be implemented in three wards — the 20th on the South Side, the 22nd on the Southwest Side and the 49th on the Far North Side — and then potentially expanded throughout the city.

Even though the three wards are home to a fraction of the city’s tenants, creating an inspection program big enough to cover them would represent a herculean effort. After all, their combined populations eclipse that of Boulder, a much smaller and wealthier city whose program developed slowly.

Boulder as a model

The kind of regulatory system that allowed Boulder officials to swiftly rectify the student-populated apartment building’s safety problems in 2016 did not develop overnight. The town spent decades building up its registration and inspection network.

Officials say the work has paid dividends, paving the way for building safety and quality-of-life programs that would otherwise have been unimaginable.

Under pressure in the 1970s from residents who lived near shoddy student-occupied housing, leaders of the city — whose population at that time was less than 100,000 — began with a voluntary list of apartment buildings under its jurisdiction. They later built the registry into a mandatory licensing system that is renewed for each property every four years.

Still, it wasn’t until after 1990 that Boulder officials started going after property owners who failed to keep tenants safe. For rare cases when building owners shirk repeated warnings and demands from the city, officials hit back with a combination of fines and public shaming, said Jenn Ross, manager of Boulder’s Code Compliance Division.

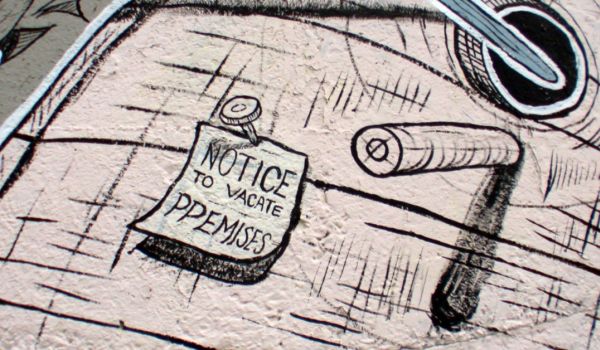

“For a building that we find to be really unsafe, we’ll tell them that all residents need to be removed from that property,” Ross said. “We post a beautiful red notice at every ingress and egress point … it’ll get on the news.”

About a decade ago in Chicago, a similar effort failed. In 2014, 7-year-old Eri’ana Patton Smith died from a fire in a Roseland apartment building with more than 150 code violations that had gone unaddressed by the city. Her father, Eric Patton Smith, pushed for an ordinance that would have required apartment buildings to post color-coded notices based on safety standards they had met. The ordinance was squashed by then-Mayor Emanuel.

In Boulder, shutting down any apartment building is a “rare situation,” Ross said. It hardly ever gets to that point because the city’s exhaustive registry helps officials keep a close eye on landlords who begin to slip.

Every landlord’s license comes with a 20-page handbook on minimum safety standards. Boulder officials hold regular meetings with real estate associations and connect small landlords with state and federal grant programs to help them fund construction and maintenance.

“We kill ‘em with education,” Ross said. “Everybody’s in the loop. And if they’re not, it’s not because we haven’t effectively communicated it out. It’s because they’re not open to that communication.”

Boulder’s apartment registry brings other benefits. City leaders say the encyclopedia of property ownership and maintenance history has been the basis for other housing initiatives, from implementing energy efficiency standards and trash disposal rules to ensuring affordable housing requirements and tightening eviction laws.

“It’s all rolling out of the rental licensing program,” Ross said. “We’re identifying all kinds of citywide issues that may need a better administrative remedy.”

Most recently, Boulder launched an interactive map showing where tenants had made service request calls around the city. Officials billed it as a way “to encourage better communications and problem-solving between landlords and renters.”

The map is “a good example of how we utilize our licensed property data to partner with other city divisions toward a common goal of safer properties,” said Tonia Pringle, senior project manager for the Boulder Department of Planning & Development Services.

It’s also a stark example of the kind of information that’s unavailable to Chicago tenants who are struggling to get landlords to pay attention to maintenance issues.

Chicago’s path forward

Tenants’ advocates in Chicago are trying to keep attention on the Healthy Homes Ordinance as higher-profile progressive priorities take up the city’s attention. At the very least, tenants’ advocates argue a registry of apartment landlords would be a step in the right direction.

When Chicago property owners refuse to fix problems like mold or rat infestations, it often falls upon tenants to force the issue or it will never be resolved, said Arieh Venick, a housing organizer with the Metropolitan Tenants Organization.

And the lack of centralized information about each landlord’s record makes it hard to hold them accountable, he said.

“When you’re able to clearly identify who your landlord is, and what other properties they might own, it’s incredibly beneficial for tenants and organizations in the city to figure out who the problematic landlords are,” Venick said.

This summer, Venick and the Metropolitan Tenants Organization helped residents of the Edison Apartments organize into a tenants’ union to push for upgrades to the building. Days before the August rally, Edison residents finally met with the building’s property management firm to discuss the issues.

“The management team has agreed to continue to communicate with the tenants since their goals are the same,” wrote Trigild attorney Cara Houck in an email to Illinois Answers. Since late last year, Trigild has made regular court appearances to show they’re making progress on building repairs. According to Cook County property records, the owner is listed as Delaware-based North Sheridan Property Investor LLC.

But it should never have fallen on the tenants to force their landlord into action, said Soto, who this year became an aide to Ald. Leni Manaa-Hoppenworth (48th).

“After we filed the 311 reports, there was no update from any of the [city] departments, so we had to keep escalating,” he said. “We want the city of Chicago to know that this does not start or end with us … we’ve already heard allegations of similar situations, and we want to show up for them as well.”

A spokesperson for the Chicago Department of Buildings did not respond to questions about safety and maintenance issues at the Edison.

While the Metropolitan Tenants Organization is still pushing for the Healthy Homes Ordinance, it has taken a back seat to the “Bring Chicago Home” push to hike taxes on high-end property sales to fund homelessness services, as well as the “Treatment not Trauma” campaign to expand mental health services.

John Bartlett, executive director of the tenants’ rights group, said building safety is linked to both issues.

“We know that being in poor housing causes stress, and it does have a real impact on people’s mental health,” he said. “We’ve shown that the city needs a different approach in the way inspections are done. So if we’re looking at everything in a comprehensive manner, then Healthy Homes needs to be a part of that.”

Ross, who oversees building code compliance in Boulder, said Chicago’s Healthy Homes Ordinance has the right idea by choosing only a few neighborhoods to test an inspection system.

“You have to start out with something small and manageable,” Ross said. “Maybe start in one ward and track staff time, track complaints, track housing code violations that they’re identifying in that area.

“Figure out the components that you want to identify before you make it citywide,” she added.

Denver, which recently created a rental registration and inspection system modeled after Boulder, scaled up its program by focusing on large, corporate-owned apartment buildings before moving to smaller walk-up buildings and then single-family homes.

Ald. Raymond Lopez (15th), who has long spoken during City Council hearings about the difficulty of addressing dangerous buildings in his South Side ward, said reform of the city’s inspection system is long past due.

“When it comes to identifying troubled buildings and bad actors in the housing providing networks, our entire system is based solely on a reactionary model,” Lopez said. “Rental certification … is something the city of Chicago needs to look at, both in terms of ensuring the quality of the housing stock, and for laying down basic parameters for what should be expected of landlords and tenants.”

This article first appeared on Illinois Answers Project and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

This article is part of Backyard, a newsletter exploring scalable solutions to make housing fairer, more affordable and more environmentally sustainable. Subscribe to our weekly Backyard newsletter.

Alex Nitkin is a solutions reporter conducting investigations on efforts to fix broken systems in Chicago, Cook County and Illinois government. Before joining Illinois Answers, he worked as a reporter and editor for The Daily Line covering Cook County and Chicago government. He previously worked at The Real Deal Chicago, where he covered local real estate news, and DNAinfo Chicago, where he worked as a breaking news reporter and then as a neighborhood reporter covering the city's Northwest Side. A New York City native who grew up in Connecticut, Alex graduated Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism with a bachelor’s degree.