The Chicago teens enrolled in urban design non-profit Territory’s programs usually spend their time exploring public spaces, designing prototype installations, and building them in a studio. But with this summer’s COVID-19 lockdown, the youth-focused design, public art, and community planning organization founded in 2012 had to figure out how to do urban design while shielded away from the rest of the city. So for the students, that meant logging on for 9 a.m. Zoom calls, applying for grants, writing a weekly newsletter, and setting up guest lectures, all via dozens of donated laptops and wifi hotspots.

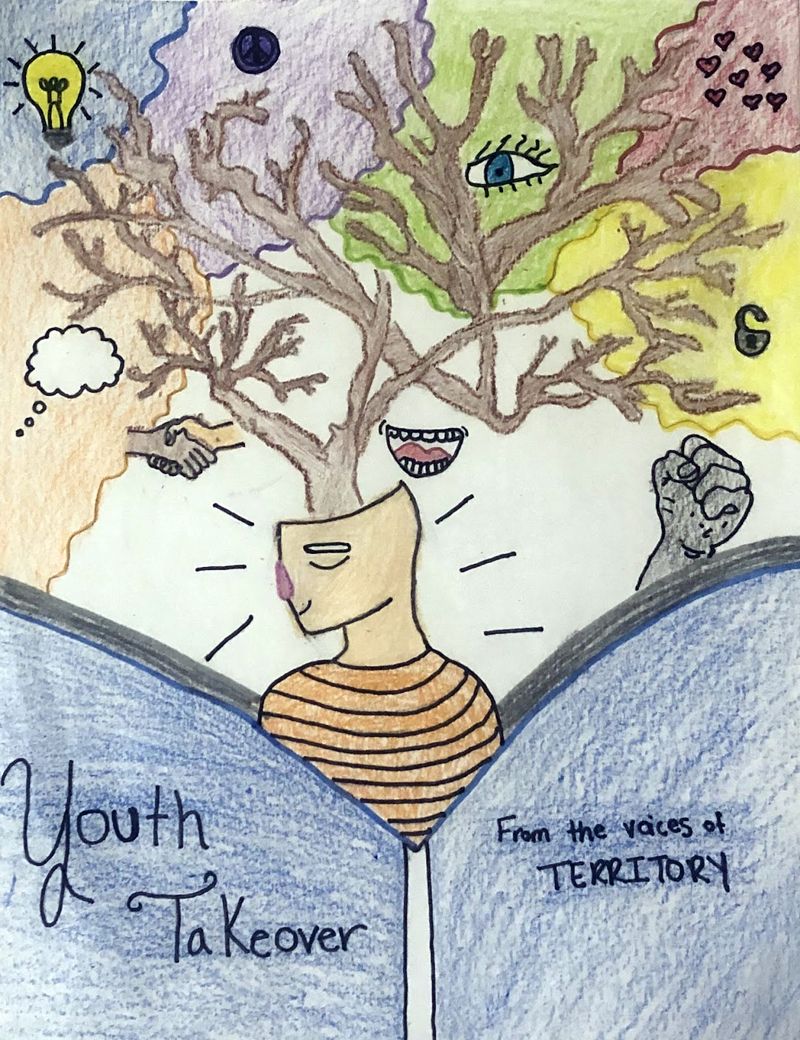

If it sounds like administrative drudgery, it’s not. Twenty high school students produced a 52-page zine that reviews Territory’s past projects and design method, and a 39-page, youth-oriented, quality of life plan for the far West Side neighborhood of Austin, where many of the students live, all produced remotely.

The quality of life report (which, like the zine, is still in draft form and not publicly available) examined youth empowerment, mental health, and public safety, during a historic summer of unrest. Through the student’s lived experiences, surveys, and analysis, they critiqued the city and institutions around them, and tracked threats to public safety posed by both a novel virus that’s disproportionately harmed disinvested, poor neighborhoods like Austin, and a perpetually festering confrontation with violent and racist policing. For the ongoing uprising and at Territory, it’s a youth-led movement.

Isobel Araujo, Territory program manager, says it’s the “purest form of youth leadership I’ve ever seen.” Though staff may suggest projects, students are entirely responsible for organizing and structuring the way they’re executed. “Territory inverts the process of inclusion and power, in that it’s not always adults coming to our team for input, [asking] ‘What is the youth perspective on this proposed bus station design?,’” says Araujo. “It’s really teenagers coming up with their own proposals and then including adults’ and professionals’ input in the teams’ designs.”

During the summer session, which lasted a bit more than six weeks, the quality of life report team gathered input from neighborhood non-profit Austin Coming Together (ACT), which released a comprehensive quality of life plan in 2018. Austin is one of Chicago’s largest and most architecturally rich communities, filled with rambling Queen Anne mansions and traditional brick Chicago bungalows. There’s a mildly suburban character to it, anchored by the Georgian Revival Austin Town Hall Cultural Center, which contributes a sense that Austin has always had its own cohesive and independent identity. The cultural center sits on the former site of the city of Cicero’s town hall, which used to encompass Austin and affluent Oak Park immediately to the west. Austin became majority Black in the 1970s, and has suffered significant disinvestment since. Forty percent of families make less than $25,000 per year, and the border between Oak Park and Austin is an unmistakable transition between wealth and deprivation.

ACT Project Coordinator Ethan Ramsay says he used his time with the Territory students to make sure that they would have the opportunity to develop and guide the “evolution and implementation of built-environment projects that happen, and inform the way they experience public safety in their neighborhood.”

The 12 students working on the quality of life plan selected several sections of the ACT report to expand on from a youth perspective, but they found one gap where they wanted to place new focus: mental health. “It’s a part of public health, and it’s also a part of making sure we’re able to sustain a movement of justice for Black lives,” says Araujo. For their study of mental health, the Territory students drafted and distributed mental health surveys, and made suggestions for small changes that could blunt the impact of trauma. One example is the Positivity Mirror, a mirror mounted on a tree with markers and dry erasers that could be used to write encouraging messages to yourself or others, boosting self-image and self-esteem.

“Small Change” design proposal, by Victoria (Photo courtesy Territory)

For the youth empowerment section of the plan, students interviewed family members on their view of youth empowerment, and contrasted Generation Z’s views on the agency of young people with previous generations. They also dug up statistics that make it clear how great the need for an engaged and critically vocal youth is in Austin: 36,000 Austin residents are 24 years old or younger, the child poverty rate is 44 percent, and local neighborhood schools lost a quarter of their students after the city shuttered four elementary schools there in 2013.

The most detailed and fully-formed element of the students’ plan is their consideration of public safety. On this section’s first page, the plan points out that “better relationships with one another” are what guide people to a better understanding of public safety, and a safer community. Later, in a section of personal interviews, the teens pose the question: “What is the difference between public safety and police?”

“The community itself needs to protect one another,” Kiara, one of the youth on the quality of life plan team, tells Next City. Because law enforcement is “not really protecting us in the way that we want to be protected, we have to depend on each other.”

Throughout, these students’ vision of public safety is nurturing and communal, focused on community solidarity and restorative justice, not policing. “It’s not carceral,” says Araujo. “It’s rooted in love and care for the community. It’s caring for people before, during, and after traumatic events.”

“Because we know the police won’t help, we have to try to do things on our own,” says JaKayla.

“An ideal image of public safety would be everyone uplifting each other,” says Toincia, “and I feel like being a part of Territory this summer, we’ve already taken a step toward doing that.”

The cover of the quality of life plan, by Kiara (Photo courtesy Territory)

All term, the Territory students were grappling with perceptions of fear and safety inside their neighborhood and beyond. “Austin isn’t as bad as people say it is,” says Travell, of the quality of life plan team. “It’s actually a really nice place, and it’s messed up that it gets the recognition that it gets compared to other neighborhoods. They think that it’s just a bad area, but actually it’s a good place to be; you gotta be around the right people.”

That summation is borne out by statistics. Despite crime headlines that perpetuate an image of the neighborhood as a chaotic morass of violence, its violent crime per-capita rate (12th of Chicago’s 77 neighborhoods) means that it’s not Chicago’s most violent neighborhood, nor particularly close to it, and its raw numbers are inflated by the very large size of neighborhood. (Nearly 100,000 people live in Austin.)

During early days of the pandemic, zine team member Victoria noticed how COVID-19 could become an invitation for invasive security surveillance, a topic that’s spawned more than a bit of high-brow architectural discourse. “In the beginning of COVID, I was actually scared to go out into downtown, mainly because people were saying, ‘You have to have a note from your doctor to go downtown.’ So I would stay at home,” she says. “I don’t know if someone’s going to come up to me and say, ‘Do you have an ID or some sort of identification that tells us that you’re supposed to be out here?’ I was kind of scared to go downtown and travel anywhere.”

The uprising against racist police violence has often been a youth-led protest movement that’s proved itself to be wholly inclusive, fluent in bending media cycles to their aims, and rapidly responsive. But Territory’s work this summer was fundamentally different in its sense of proactive planning that addresses some of the root causes of the protests. The teens spend lots of time “visualizing the just city,” says Araujo. “Not only are young people demanding a better city right now, they’re thinking ahead, and that’s what planning and design is supposed to do.”

Like everyone else, the Territory students are working through the atomization and isolation of the COVID-19 crisis to find collective agency, especially needed when the adults running things aren’t interested in making room for their voices. “Each individual is powerful in their own way, but to have a whole group of powerful teenagers is what makes it stronger than just one adult putting us down,” says Victoria. “We’re stronger as a whole.”

Zach Mortice is a Chicago-based design writer and critic, focusing on architecture and landscape architecture. He’s written for numerous national design publications, and is the editor of Midwest Architecture Journeys, from Belt Publishing. You can reach him at zachmortice@gmail.com, or follow him on Twitter and Instagram.