Marta has lived with a bad smell lingering in her hometown in central Spain, Villanueva del Pardillo, for a long time. Fed up, in 2017 she and her neighbors decided to pursue the issue. “The smell is disgusting,” Marta says, pointing a finger at a local yeast factory.

Originally, she thought of recording the “bad smell days” on a spreadsheet. When this didn’t work out, after some research she found Odour Collect, a crowdsourced map that allows users to enter a geolocalized timestamp of bad smells in their neighborhood.

After noise, odor nuisances are the second cause of environmental complaints. Odor regulations vary among countries and there’s little legislation about how to manage smells. For instance, in Spain some municipalities regulate odors, but others do not. In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency does not regulate odor as a pollutant, so states and local jurisdictions are in charge of the issue.

Only after Marta started using Odour Collect to record the unpleasant smells in her town did she discover that the map was part of ‘D-NOSES’, a European project aimed at bringing citizens, industries and local authorities together to monitor and minimize odor nuisances. D-NOSES relies heavily on citizen science: Affected communities gather odor observations through two maps — Odour Collect and Community Maps — with the goal of implementing new policies in their area. D-NOSES launched several pilots in Europe — in Spain, Greece, Bulgaria, and Portugal — and two outside the continent in Uganda and in Chile.

“Citizen science promotes transparency between all the actors,” said Nora Salas Seoane, Social Sciences Researcher at Fundación Ibercivis, one of the partners of D-NOSES.

It’s easy to measure smells coming right out of a factory exhaust pipe or a sewer. It’s not so easy to understand how those smells will disperse into a neighborhood. Trees block smells or car traffic muddles them; changing weather conditions affect how odors move through a city. “One of the objectives is demonstrating that there is a problem,” says Salas Seoane. “Data can inform improvements in industrial operations.”

Citizen science also helps add rigor to observations. “If you’re from Barcelona you know that in the Forum area there’s a problem with odor,” says Salas Seoane. The Forum Area, in the north-east end of Barcelona, was renovated in 2004 ahead of the “Forum of the Cultures.” Several waste treatment facilities are based in the historically disinvested area, and, depending on weather conditions, fresh wastewater, sludge, or biogas smells are dispersed in the area. The area started to be mockingly called by locals ‘Ferum’: ‘bad smell’ in Catalan.

Researchers used different strategies to engage the citizens. “We spent time giving out flyers, going to gyms, supermarkets, and participating in community events,” says Salas Seoane. They trained citizens on how to use Odour Collect, and organized sensory walks through the Forum Area, where locals identified the different smells. The pilot prompted conversations and collaboration on the D-NOSES with the Barcelona environmental authority — the public administration in charge of the city’s environmental planning and that manages most of the emitting activities of the area.

Using the Odour Collect app (Photo courtesy D-NOSES)

Other pilots have similarly engaged the community, although the specifics are different. In the case of Thessaloniki, Greece, believing in citizen science was a matter of faith. When researchers went to the local church, “it was the priest himself who volunteered and spoke to the community,” said Maria Alonso, business development executive at Mapping for Change, another partner of D-Noses. After the local priest’s intervention, citizens started reporting the odor emissions of a local refinery. In another pilot, in Porto, locals were invited to report odors on their walks on a path along the Rio Tinto to identify the state of the river, where discharge sewers polluted the area.

Though D-NOSES is a European group, there are odor complaints on Odour Collect’s map on all seven continents. (That said, “User475”, who reported rotting waste at the O’Higgins research base in Antarctica, may have just been yanking everyone’s chain.) “Odor pollution is happening everywhere,” says Alonso.

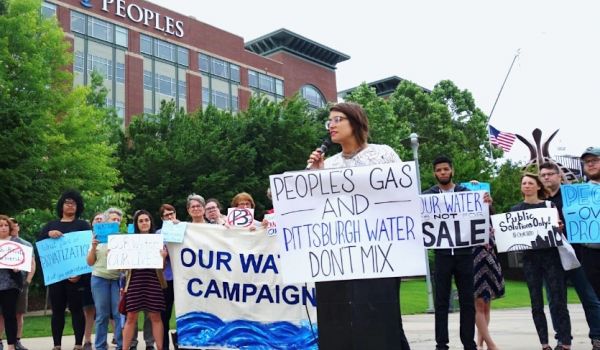

There are smell mapping projects in the U.S. as well. The Create Lab of Carnegie University has created Smell Pittsburgh, a crowdsourced mobile app with a map that keeps track of smell and pollutant emissions and reports them to the Allegheny County Health Department. The stakes here are not just bad smells: Allegheny County received an ‘F’ from the American Lung Association in its 2021 State of the Air report.

Back in Spain, Marta has been able to get almost a hundred of her neighbors in Villanueva del Pardillo on board with her plan to record odor nuisances on the Odour Collect map. Looking for more tools to escalate their complaints, Marta has been in touch with the developers of the app and asked for the analytics to have precise data on how many people were actually registering the smells, how often, and what kind of odor nuisances they were perceiving.

“My goal is to send something in writing to the mayor of the city,” says Marta. “Attach the analytics and say: ‘Look, a hundred neighbors have reported this smell during this period,’ so that the authorities know that this is not something that we make up, but there is proof, there is evidence from the map.”

Lucrezia Lozza is a freelance journalist and documentary maker, specializing in social and environmental issues. She writes in English and Italian. She has worked as a staff journalist for Reuters and reported for international media such as The Independent, Raconteur, Earth Island Journal and Equal Times.