Having Grandma, Grandpa and the grandkids under one roof used to be a fairly common arrangement among American families before they went nuclear and moved to the suburbs in the years following World War II. (Even after that, one could find examples of the old model here and there. I recall how my mother’s mother lived with one of her daughters in a bedroom of her Kansas City home until her death in 1971. While that worked for her, there are those, such as Saufan Fung of Philadelphia, who would prefer a living arrangement that affords more privacy than that. Fung shared her opinion for Next City’s recent street survey of Center City Philadelphia elders.)

Now, thanks in part to the aftershocks of the Great Recession, the multigenerational living model is coming back. Whether it’s young millennials moving back in with their parents after college in order to save money while launching their careers or Gen X adults seeking to make room for their boomer parents, people are increasingly demanding spaces that allow two or more generations to live independently together by putting a home within a home. (As Edward McClelland explores in Next City’s Forefront feature, “The All-Ages City,” planners are also grappling with this shift from a citywide perspective.)

The multigenerational home has a long provenance, going back to the “granny flat” over the garage of a detached early-20th-century home or the “in-law suite” with its own entrance in that same home. Suburban developers have responded to the trend by offering products like Lennar’s “NextGen” home, which contains a small “apartment” with its own separate entrance within the traditional single-house envelope.

Urbanites, however, have yet to find this option widely available to them. But architects are working on bringing it to them. Two examples from opposite coasts show how creative minds are adapting the multigenerational model to their own cities’ housing stock.

San Francisco architect Brandon Baunach began thinking about the subject when he and his wife decided to have a family. Baunach, whose work includes numerous apartment complexes for seniors, realized that even with a decent income, adding children to the mix became too much of a financial burden in that notoriously expensive city.

“We didn’t want to spend $2,500 a month on child care for two children,” says Baunach. “And our mom was living nearby. So we made a strategic decision. ‘You take care of the kids, and we’ll take care of you when the time comes.’ And we decided to buy a house together in San Francisco.”

That’s when he ran into a wall. “We found there were only two options: Buy a duplex or buy a house with an in-law apartment. But until very recently, in-law units were illegal. And with duplexes, we would have had to evict everyone in the duplex in order to take it over — and in one instance, that involved a person with an oxygen tank.

“So even though we had a good budget, there was no product that would allow us a level of separation while also allowing for togetherness.” Baunach ended up having to move across the Bay to Berkeley to get the living arrangement he wanted.

There’s also a personal element to Philadelphia architect Laura Blau’s effort to develop a rowhouse that can change as its owner’s needs change. “I’m in my late 50s, and the house I live in now would not be suitable for me to age in place,” she says.

Architect Laura Blau is rethinking the typical Philadelphia rowhouse to allow for aging in place. (Graphic from BluPath Design)

The solutions Blau’s BluPath Design architectural firm and BAR Architects, where Baunach works, are developing are each rooted in their own cities’ urban ecologies.

BluPath’s “Transformer” house takes the standard rowhouse, doubles its width, and lowers its first floor a few feet. This makes possible the creation of an accessible street-floor apartment of about 30 by 50 feet — “a nice, comfortable living area for a couple,” Blau said. The space is large enough to accommodate a one-bedroom apartment whose entrance is shared with the unit on the floors above. It also is designed so that an elevator can be added to connect the units by inserting the shaft in utility closets on each floor.

With the potential for anywhere from one to four units on the floors above, the house could also offer an opportunity for its owners to offset operating costs by renting out units until it’s time for the owners to use them. Those costs, however, are also lower by design — the house is engineered to meet passive-house standards, which means its net energy consumption would be zero or as close to it as possible.

“It’s a real Rubik’s Cube,” she says. “It takes a lot of thought to be able to have these multiple functions in a comfortable and low-cost-to-run building, which is another factor for people on fixed incomes. It’s a big project, and interesting.”

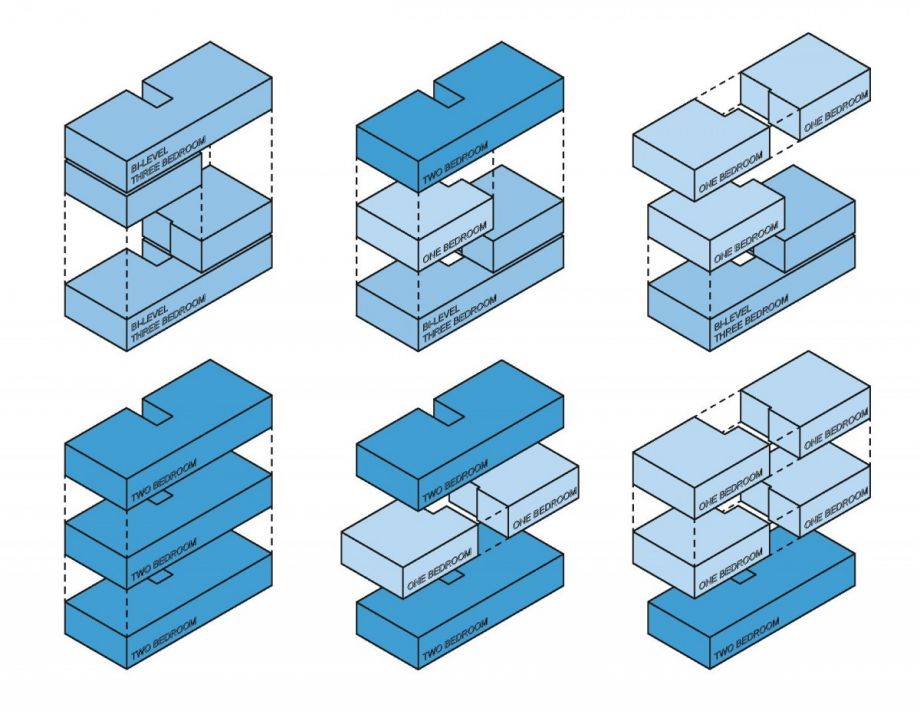

Baunach’s idea takes the concept to the world of multifamily housing — apartments and condos — by borrowing from the world of hotel design: Create two units with a common shared space that can be accessed from either unit and doors that allow the two units to be used separately or together as the owner desires. In the hotel, that space is often a living room that turns the two units into a suite; in BAR’s prototype, the common space is the laundry room both units share.

“It’s incredibly basic,” he explains — akin to purchasing a studio and a two-bedroom apartment together. It also offers a more family-friendly alternative to one of the hottest trends in affordable housing, one that would allow buyers or renters to remain in the neighborhoods they love.

“What’s popular in ‘affordable by design’ housing now is the micro-apartment,” he says. “But micro-units don’t work for families.”

There is another challenge to bringing these designs about, however: changing local zoning laws to allow for their existence.

“Planning departments hate this because they see it as overcrowding,” Baunach notes of his design. “But it’s no more dense than micro-units.”

Similarly, Blau’s house couldn’t be built in many Philadelphia neighborhoods, where the most common residential zoning category stipulates single-family rowhouses. “To really make this work, you have to have multifamily zoning from the get-go — you can’t start as one thing then go back and fight for the zoning later on,” she says.

“Because everyone is in the ‘how things are at the moment’ thinking and not thinking about how things are going to be, getting these zoning changes will be difficult,” she adds. “I think we need to have more flexibility in the city now to accommodate future uses.”

Blau is currently seeking investors to allow her to continue development of her concept.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Next City contributor Sandy Smith is the home and real estate editor at Philadelphia magazine. Over the years, his work has appeared in Hidden City Philadelphia, the Philadelphia Inquirer and other local and regional publications. His interest in cities stretches back to his youth in Kansas City, and his career in journalism and media relations extends back that far as well.

Follow Sandy .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)