As Washington, D.C.’s new Metro Silver Line rolls out from the city into the growing suburban counties of Virginia and Maryland, officials and planners in those regions are faced with decisions about what development around their new transit stations should look like. Whether they approach the design process with a suburban or urban mindset will have a decades-long impact in those communities.

Responding to its dozen new miles of rail, Fairfax County, in northern Virginia, has undertaken a comprehensive rezoning effort, seeking to urbanize the area called Tysons Corner especially. (This urbanizing approach is echoed in Montgomery County, Maryland, which is featured this week in our Forefront on how the North American suburb is growing up.) While Tysons will take a generation or two before it’s fully built out, its ultimate transformation into a dense corridor forged out of typical suburbia, much like the Rosslyn-Ballston string of towns along the Orange Line in Arlington County, seems very likely.

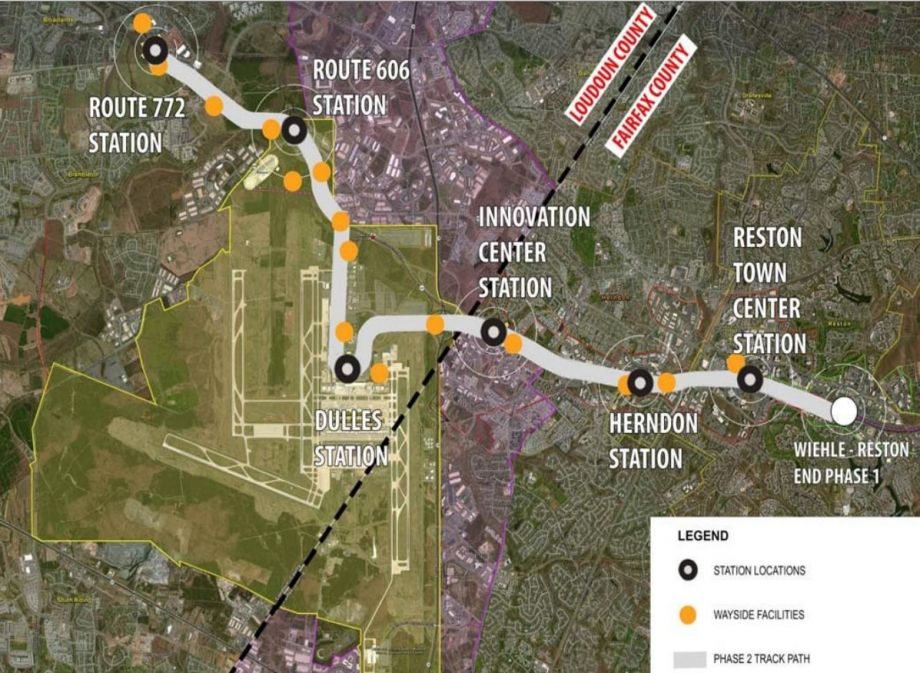

In Reston, which is getting three Silver Line stations, the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors approved a plan that will allow for thousands of apartments at each of the stops and a few million square feet of office space, with nearly twice as many new homes (27,900) as first planned.

The Silver Line’s final frontier lies in Loudoun County. Past Dulles Airport, well over an hour from the center of Washington, D.C., Loudoun’s two stations have not yet been named, and are still known by the roads they intersect, which form pedestrian-unfriendly cloverleaf interchanges. Of the rail extension’s 23 miles, the last mile or so in Loudoun County will likely be the most difficult part to urbanize.

Chris Leinberger, a developer and professor at the George Washington University School of Business, just participated in an Urban Land Institute panel that gave recommendations to the Loudoun County Board of Supervisors about urban plans for the stations. With the second phase of the Silver Line extension — to Dulles and Loudoun County — due for completion in 2018, the county is beginning to draw up plans for the area.

The panel’s main recommendation? Build more housing.

Relying solely on office development, Leinberger says, “has been a very effective strategy for them in the 20th century. They were able to get AOL and a variety of other, what they call ‘keynote’ offices, but it hasn’t worked in this century.”

“The office market,” Leinberger explains, “is in a structural transition.” Firms are leasing less space, and the ULI panel doubted Loudoun’s projections that it can double its existing 19 million square feet of office space by 2040, saying the number could in reality be as low as half that.

“Residential is a mere 60 percent of the built environment,” says Leinberger. “If you don’t get residential, what do you have? If you don’t have residential, you aren’t going to build a vibrant walkable place” — something that ultimately may be an impediment to attracting office space, too.

The other problem Leinberger sees in Loudoun — but which he said the county was committed to — is parking. “They’re building a ton of it,” he said. “They’re building thousands of decked parking spaces at those two Metro stations.” At least, he said, they’re not building surface lots.

“Loudoun County is to be complimented phenomenally for taking what is the penultimate drivable suburban place and agreeing to pay for the extension of Metro out there,” Leinberger says of their effort. Whether they’ll take ULI’s advice for maximizing the land’s potential — “those 2,000 acres are their economic future as a county,” he told the supervisors — remains to be seen.

“The jury’s out,” says Leinberger, “but they’re certainly asking the questions.”

The Works is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Stephen J. Smith is a reporter based in New York. He has written about transportation, infrastructure and real estate for a variety of publications including New York Yimby, where he is currently an editor, Next City, City Lab and the New York Observer.

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)