Washington, D.C., has a well-chronicled and long-standing rat problem — 50 years ago, Congress even declared a “War on Rats” and employed a staff of over 100 exterminators to fight the furry pests. But the war still hasn’t been won. According to WAMU, complaints about the rodents more than doubled between 2015 and 2017, so the city is trying out a different strategy: data science.

The Lab @ DC, a new team that uses data to tackle municipal issues, is creating a computer model to target the rats with greater precision, WAMU reports. Rat hunting, it turns out, is like just about every other urban issue — it tends to benefit the wealthy and privileged and leave lower-income neighborhoods and communities of color behind. That’s because exterminators focus most of their effort on responding to complaints, but not everyone who might (literally) smell a rat complains. Things like language barriers, immigration status and poor relationships with local law enforcement may very well discourage a needed 311 call.

The inequitable distribution of city-sponsored rat fighters has a long history in D.C. As Smithsonian Magazine reported several years ago, one famous ‘60s-era activist supposedly trapped rats in black, working-class neighborhoods, strapped their cages to his station wagon, drove to Georgetown and let them loose. Georgetown was then, as to some extent now, home to many politicians and residents who were whiter and wealthier than the rest of the city. His reasoning was that a “D.C. problem usually is not a problem until it is a white problem,” as a piece in The Washingtonian reportedly summed up his unique brand of direct action.

The computer model being developed by the Lab team tries to predict which city blocks will most likely be rat-infested based on a number of environmental variables, not just 311 calls. WAMU reports:

The team at The Lab scoured data from just about every city agency — everything from property tax records to business licenses — to get information on things like building age, building condition, population density, number of restaurants, size and condition of alleys, location of sewer grates and the location of parks and community gardens.

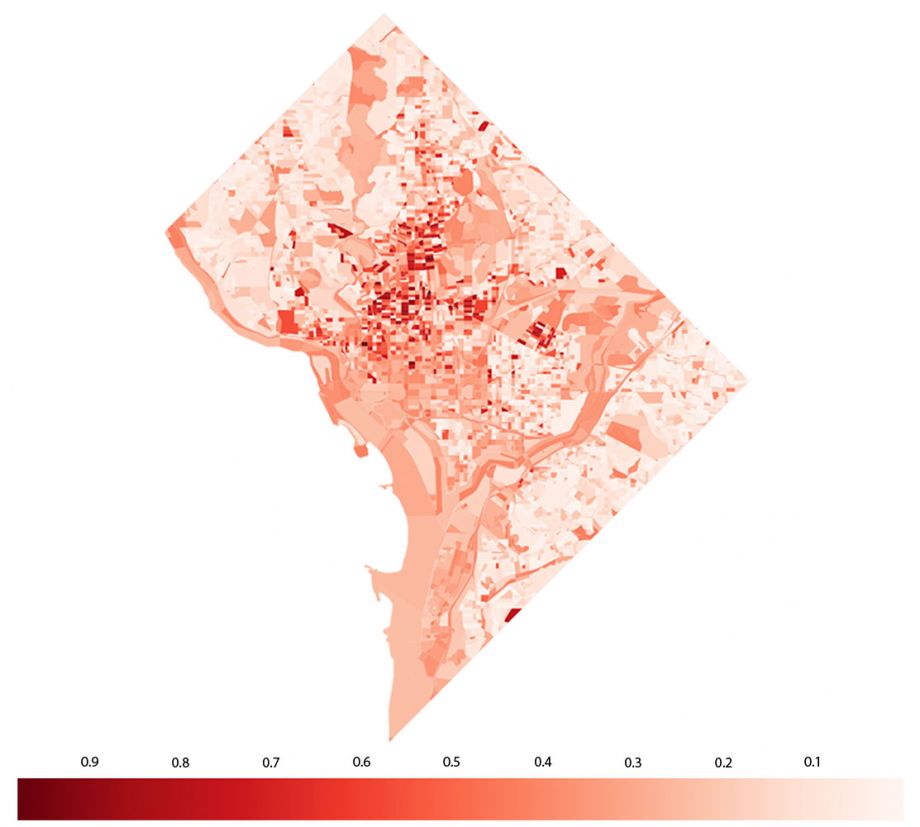

The model has produced a map of the District with every block in a different shade of red. There’s a clear pattern: The most densely populated neighborhoods show a higher likelihood of rat infestation. Dark red radiates from downtown up through Dupont, Columbia Heights and Petworth, out along H Street and in Trinidad, and in Georgetown and up Wisconsin Avenue.

“When you have lots of people living in close quarters you’re producing more and more trash in a smaller and smaller area and you’re producing more potential food for rats,” Peter Casey, a data scientist and a fellow with the Lab, told the station.

Using data to fight rats is not an entirely new concept for cities. As Henry Grabar reported for Next City in 2015, the city of Somerville, Massachusetts, has had a good deal of success tamping down on rat food supplies (i.e., garbage cans). Targeting the city’s trash stream might seem like an obvious way to combat rodents, but data analysts actually suggested the tactic, since city officials were mostly concerned with rat sterilization and preventing new rats, rather than the animals’ food supply.

Rachel Dovey is an award-winning freelance writer and former USC Annenberg fellow living at the northern tip of California’s Bay Area. She writes about infrastructure, water and climate change and has been published by Bust, Wired, Paste, SF Weekly, the East Bay Express and the North Bay Bohemian

Follow Rachel .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)