An urban heat island — a metro center that is significantly hotter than the surrounding region — is actually less island and more archipelago, a new study points out. A neighborhood with particularly dense housing or sparse vegetation is going to be hotter than a neighborhood made up of single-family homes, established trees and lawns. Thus the built environment creates “hot spots” throughout cities, and they often follow patterns of income and racial disparity.

Like painted streets, green roofs can help cool those hot spots — and for a paper published in Environmental Research Letters, researchers have crafted a framework to identify which neighborhoods need them most.

The paper focuses on Chicago, but there’s insight for leaders in other cities.

“We wanted to look at the potential of these types of mitigation strategies through the eyes of the mayor, city manager or city planner,” said Ashish Sharma, a research assistant professor at the University of Notre Dame who led the study, in a media release.

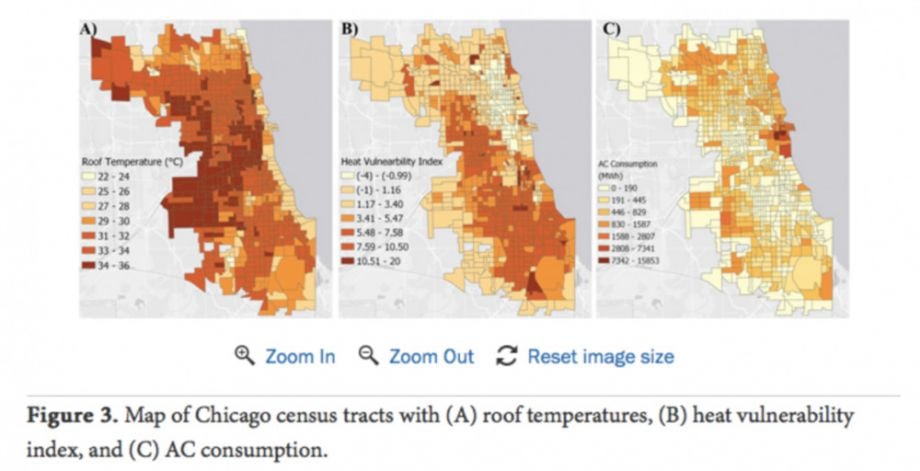

The researchers examined temperatures, electricity consumption and socioeconomic vulnerability of census tracts to identify hot spots in Chicago. The team simulated temperature data and used publicly available electricity consumption numbers and figures from the Centers for Disease Control and the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. Layering those different data sets was important because alone, certain figures, like air-conditioning use, don’t capture the whole story.

From the Notre Dame release:

Looking only at electrical consumption, those areas where air conditioning is used most, for example, may not account for affluence. In certain neighborhoods, residents can afford the cost, which ultimately makes them less vulnerable. In lower-income neighborhoods, some residents can’t afford to turn their air conditioning on, or don’t have access to air conditioning at all.

The lack of air-conditioning use in those neighborhoods could lead policymakers to believe residents weren’t as impacted by heat — when, in fact, they simply didn’t have access to or could not afford AC.

(Credit: “Role of green roofs in reducing heat stress in vulnerable urban communities—a multidisciplinary approach,” Environmental Research Letters)

As Next City has covered, features like green roofs and urban tree cover can save cities a lot of money in electricity and health-related costs over the long term. Other researchers have tried to quantify those factors in cities like Philadelphia and Washington, D.C.

Los Angeles, meanwhile, has looked lower and darker than green roofs, as Next City covered last year. In 2017, the city started painting some streets light gray, making reflective “cool pavement” to lower temperatures.

The full University of Notre Dame report on Chicago is available here.

Rachel Dovey is an award-winning freelance writer and former USC Annenberg fellow living at the northern tip of California’s Bay Area. She writes about infrastructure, water and climate change and has been published by Bust, Wired, Paste, SF Weekly, the East Bay Express and the North Bay Bohemian

Follow Rachel .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)