Animo Leadership Charter High School in Inglewood, California (Photo by John Linden)

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberThis feature is an excerpt from a new book out from Island Press, “Design for Good: A New Era of Architecture for Everyone,” by John Cary.

An architect by training, I’ve always been fascinated watching people experience design and the world around them. I believe that design functions in our lives like the soundtrack that we’re not even fully aware is playing. It sends us subconscious messages about how to feel and what to expect. It’s what environmental psychologists have long described as “place identity” — essentially that the foremost building blocks of our sense of self are actually the spaces in which we live, work and play. It’s what I have to come to simply call dignity.

What inspires me to write about design operates on two levels. On one level, my motivation is deeply pragmatic: I want to change the practice of architecture and design. I want to alter how we build and who we build for. On another level, I’m a believer in the power of design to change lives and to bring dignity to average people, the disenfranchised, and the poor.

In a time of such heightened inequality, the ethical dimension of design has never felt more important. Well-designed spaces are not just a matter of taste or a question of aesthetics; they literally shape our ideas about who we are and what we deserve in the world. That is the essence of dignity. And both the opportunity and the responsibility of design.

Across the world, I have found projects that hold lessons for those who want to dignify their lives and our shared world through design. Drawing on insights from my interview subjects and buildings they created together, I’ve identified five key lessons.

In our work lives especially, we are conditioned to think of or present ourselves as “experts.” This assumes our studies, experiences, and skills establish a level of expertise worth imparting to others. But it risks our thinking that we have all the answers to a given problem without taking the time to fully understand the nuances of a situation, sometimes even blinding ourselves to the bigger picture. Embracing a “beginner’s mindset” is one way that all building contributors can not just humble ourselves, but also gain entirely new knowledge and perspectives in the process.

A beginner’s mindset is a linchpin of the practice of human-centered design. One of the world’s best-known firms, IDEO, and its nonprofit spinoff, IDEO.org, have emerged as two of the biggest advocates for human-centered design. IDEO.org cofounder Patrice Martin explains it this way: “What designers bring is the potential for new answers. While problems and needs may appear well-defined at the outset, we use a beginner’s mindset to take a step back and to breathe life and creativity into projects.” Martin tells me, “It’s about bringing in a fresh perspective and permission to look at the wider problem.”

In their own ways, all building project stakeholders — clients, users, laborers and others — have the potential to bring, and benefit from, a beginner’s mindset. The non-architects involved may very well be the best positioned to fuel innovation because of their perspectives. For me, that doesn’t necessarily mean that those stakeholders will all belly up to tables with butcher paper and crayons to “codesign” projects, in the spirit of yesteryear’s focus on “participatory design.” Being human-centered doesn’t mean denying that certain kinds of training prepare some people to drive the process and make important decisions at key moments. Instead, it means that all perspectives will be sought, heard and honored throughout the design process.

The Butaro Hospital is the most storied example of a group of designers learning on the job. The group of Harvard graduate students inadvertently didn’t make the same, often detrimental design decisions made in hospitals around the world, in part because they simply weren’t experienced enough to be blinded by protocol. Their unorthodox decisions were driven by naïveté and necessity. They contended with issues such as limited electricity, an extremely tight budget, and the need to ensure natural airflow to safeguard against communicable diseases. Those limitations pushed them as designers and, ultimately, made the hospital more — not less — dignifying.

Other notable designers have never undertaken the particular project types they were presented with. Marina Tabassum’s invitation to design a mosque in her home city, Dhaka, Bangladesh, is a prime example. Through research and her own intuition, Tabassum was able to forgo the symbols — domes, minarets, and the like — pervasive in so many other mosque designs. Her beginner’s mind led to an elegance that simply would not have been possible were she wedded to a “because we’ve always done it that way” mentality.

Women work in Hellen's House in Nakuru Kenya. Hellen's House was completed by Orkidstudio in 2015. (Photo by Peter Dibdin)

The best practitioners are distinguished in seeing and treating the people they build with as partners, not clients. Money is obviously necessary to getting the work done, but it’s not at the center of the relationship. And the relationship is reciprocal, not transactional, built on genuine respect for the insights that everyone brings.

When people feel like partners, not clients, they tend to want to work together over and over, as evidenced by repeat collaborations such as Skid Row Housing Trust’s multiple projects with Michael Maltzan Architecture in Los Angeles and MASS Design Group’s recurring work with both Partners in Health and Les Centres GHESKIO. It’s also apparent in the way partners and designers talk about tackling difficult challenges together — solving problems, not pointing fingers.

You can see the value of this kind of collaboration at The Cottages at Hickory Crossing, a community for the 50 most chronically homeless people in Dallas. Central Dallas Community Development Corporation and the architects at bcWORKSHOP sat side by side in the same office over many of the years that they jointly worked on the project. It was a long haul, full of daunting bureaucratic and funding hurdles, but they stuck with it because they stuck together.

On the campus of Kalamazoo College in Kalamazoo, Michigan, Studio Gang and the college were able to work closely with an unusually design-conscious funder, the Arcus Foundation, to push through several challenging features now central to the success of the college’s Arcus Center for Social Justice Leadership. The foundation gave the support the architects needed to experiment with an innovative exterior facade, and a hearth and kitchen unusual for a public building. Designed to foster dialogue, the latter two features required special approval and a shared commitment to seeing them through despite the odds.

It’s important to acknowledge that individuals and entities undertaking design projects for the first time are putting just as much or more on the line as designers. To reap the full rewards of partnership, designers also have to take risks and push themselves. When both groups do, the payoff can be transformative.

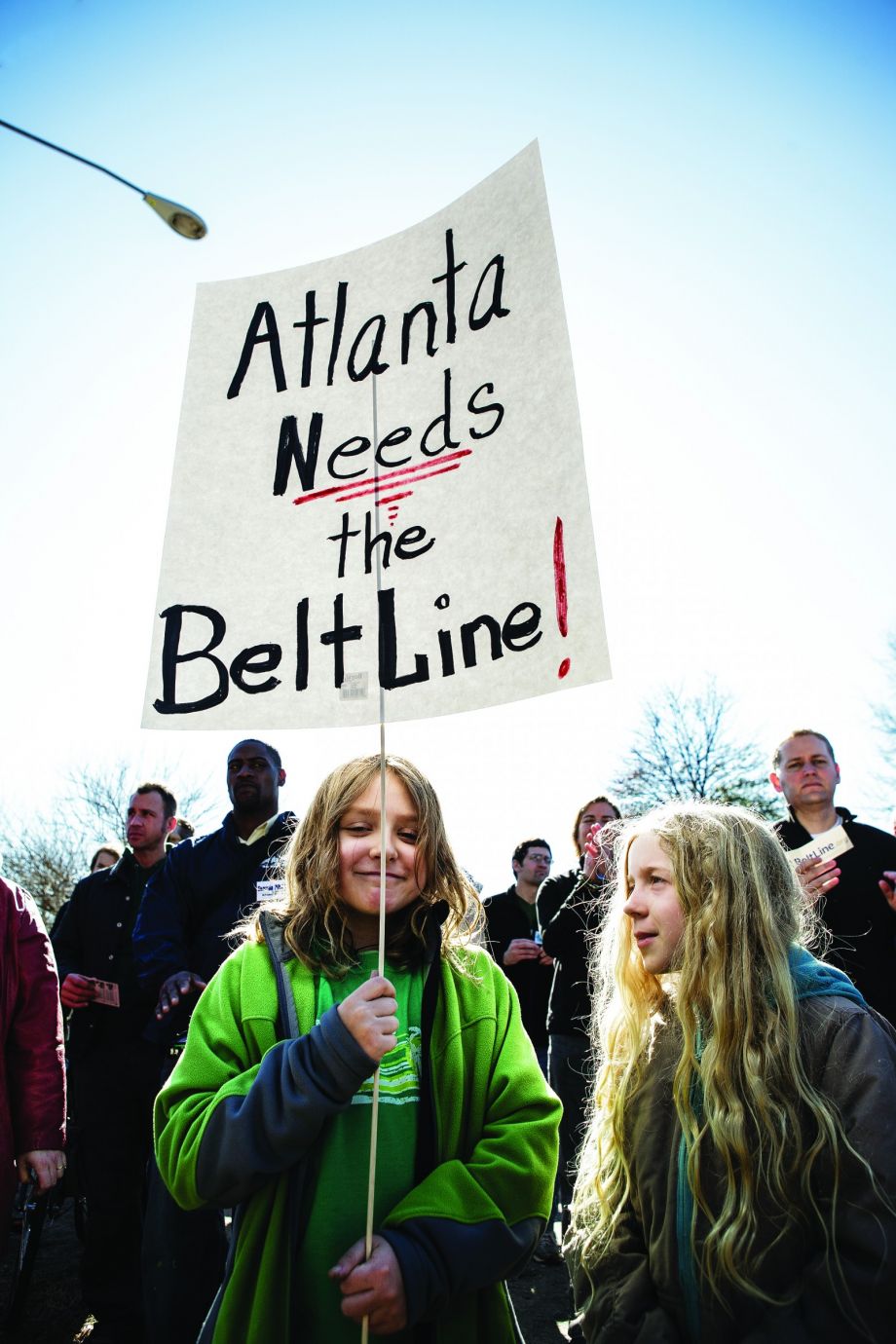

BeltLine advocates of all ages rally to show support. (Photo by Christopher Martin)

Traditionally, when it comes to built projects, the public has been seen as “stakeholders,” at best, and a hurdle, at worse. Architects and their partners actually have an exciting opportunity to rally support for projects — to turn the public into a community. This isn’t just about getting approval from a city council or planning department, important as that may be. It requires that designers, in particular, listen deeply to community needs, reflect those needs back to the stakeholders, and reinforce their understanding over time.

This goes beyond just “educating” the public, as it is often described; this is about imagining the potential impact together, building excitement around a project, and doing so collaboratively from an early stage. It is about seeing the public as the lifeblood of a future building, not an obstruction to appease. That kind of relationship-building does wonders, not just for the reception of the original project, but for its long-term health. A community that “owns” a building or landscape project that benefits from it in terms of their own quality of life, is one that takes care of it over time, no matter the economics.

Immersing designers in communities, especially ones that they are not native to, is another meaningful way to gain crucial insights and build community support. When designers live among and with their partners, windows into the real, lived experiences of people, beyond the confines of an interview or focus group, open up. Relationships form around more than just the building objectives; they form around genuine discovery of living together, asking questions, learning about one another’s quirks and qualities. That makes for a much stronger foundation for a building than any formal setting.

Because of the cost and time required to transport an excavator from Rwanda’s capital city, Kigali, the Butaro Hospital site was excavated by local laborers. (Credit: MASS Design Group)

Yet there is a disproportionate number of projects built outside the United States that succeed most clearly on this front. When I mentioned the importance of local labor and materials in MASS’s work in a keynote address for the American Institute of Architecture Students a couple of years ago, a student afterward asked, “Why aren’t U.S. projects held to that same standard?”

Talk about a great “beginner’s mind” question. Indeed, why? Architects such as Michael Maltzan working on L.A.’s skid row highlight very real challenges to that goal for projects within the United States. In Maltzan’s case, the prefabricated construction method of a six-story apartment building designed to be permanent supportive housing for formerly homeless individuals was already a stretch to get through city planning. Without viable options for those prefabricated units locally, Maltzan’s firm had to go far outside the region, trucking materials in from out of state. After the project, Maltzan commendably set about working with the city to advocate for prefabrication, including local manufacturing facilities.

Brent Brown and bcWORKSHOP ultimately made a similar concession regarding the labor for their affordable development in Dallas. Despite extensive lead time on a nearly decade-long project, when construction finally got under way, the organization abandoned its goal of employing future residents in the construction; it felt more compelled to get the units built quickly and get the residents into their homes. It’s understandable that the partners involved in this project sacrificed their original aspirations for local labor, and yet what was lost in the process? We’ll never know.

But new projects have the opportunity to find out. What lives might be transformed with new vocational skills and the inevitable boost in confidence that comes with being an integral part of a team that really and truly makes something? As the U.S. and other countries speculate about how to bring jobs back to underserved communities, recommitting to using local labor in all building projects is a small, but not insignificant, place to start.

A cluster of classroom pavilions are aglow as night falls. (Photo by Elizabeth Felicella)

Those interested in the social and economic impact of buildings have a viable precedent in the U.S. Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program. LEED certifies buildings and even entire neighborhoods on the basis of an array of factors including energy efficiency, water usage, and proximity to transit, among many others. It also accredits individual professionals — from a wide range of disciplines, not just design.

Since the LEED rating system’s launch in 2000, nearly 80,000 projects — representing more than 15 billion square feet of commercial and institutional space as well as 250,000 residential units — have been certified as part of the program. These projects are located in all 50 U.S. states and in 161 countries and territories. Without national or international standards such as LEED’s, design firms, organizations, and their partners in building projects are left to their own devices to determine what to measure regarding social and economic impact and how to do so.

Some organizations, for a variety of reasons, including their dependence on philanthropic funding, are investing heavily in assessing their impact. MASS Design Group, once again, maintains a robust spreadsheet accounting for overall costs as well as breakdowns for labor, materials, and transportation, among many other indicators. The organization tracks those costs that fall within the immediate local community (MASS considers anything within a radius of 100 kilometers, about 62 miles, to be local and anything within 800 kilometers, about 497 miles, to be regional). In addition to carefully tracking the number of people employed in the construction of its buildings, MASS works with its partners to track the primary and secondary users of their spaces, year over year.

Other entities such as Central Dallas Community Development Corporation, Satellite Affordable Housing Associates, and Maltzan’s client in L.A., Skid Row Housing Trust, all track impact by their own metrics. As repeat clients, they each have the added benefit of being able to track data across similar projects, providing points of comparison. In many respects, the Atlanta BeltLine has the ability to do the same, across many neighborhoods and conditions, to see how its trails and parks function.

It’s time for rigorous assessment of impact to become standard for all buildings, with funds allocated to do so. One existing, if little used tool is the post-occupancy evaluation—a rigorous study that asks users about their actual experiences of buildings paired with observation of users’ behaviors, most often conducted by third parties. Such data can ensure that the best or most successful aspects of buildings are understood and challenges are remedied or not repeated in future projects. Post-occupancy evaluations are occasionally administered by government agencies, such as the Department of Housing and Urban Development or the General Services Administration in the United States, but are rarely included in a project scope.

Just as the nonprofit sector has become vigilant about utilizing independent researchers to evaluate the impact of their work — frequently in the form of “randomized control trials,” popularly known as RCTs — it’s time for those of us who build to get curious about how our creations stand up in the long run.

An architect by training, John Cary has devoted his career to expanding the practice of design for the public good. “Design for Good: A New Era of Architecture for Everyone” is Cary’s second book, and his writing on design, philanthropy, and fatherhood has appeared in the New York Times, on CNN.com, and in numerous other publications. Cary works as a philanthropic advisor to an array of foundations and nonprofits around the world, and he frequently curates and hosts events for TED, the Aspen Institute, and other entities.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine