Austin's Art From the Streets offers studio space in which unsheltered people can safely practice their art. Although the studio has had to close for the duration of the pandemic, online art sales and delivering art kits have been ways to support their creators.

Photo courtesy Art From the Streets

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberLarry Williams has been surrounded by the arts most of his life. He grew up in Tennessee with parents who both taught music and drama at the college level. The practice room for the black students at the time was in his home, where he says, they housed four pianos.

“Music and art were dramatic themes in my childhood,” he says.

He moved away from art and painting during his adolescence, when he was more interested in boxing and baseball. And didn’t encounter a paintbrush again until about 40 years later.

“I went through a divorce — a mid-life crisis,” Williams says. “Homelessnesss was something I had never considered, intimately. It comes to you…not only fast, but dramatically.” He was living at Austin Research Center for the Homeless (ARCH) when he encountered Art From the Streets (AFTS). The program gave him a haven from the “culture shock” of homelessness, he says.

AFTS is a nonprofit that started 12 years ago to give people living with homelessness a way to make and sell their original artwork at an annual art show. It’s run by a board of volunteer directors, who manage the website and inventory, and provide the open studio space and high-quality art supplies for the artists — mostly acrylic paint, pastel or charcoal and paper.

“What I found out was they had a lot of paper, and a lot of paint. But most of all they had people [who] were always there when they said they would be,” says Williams. “They were present.”

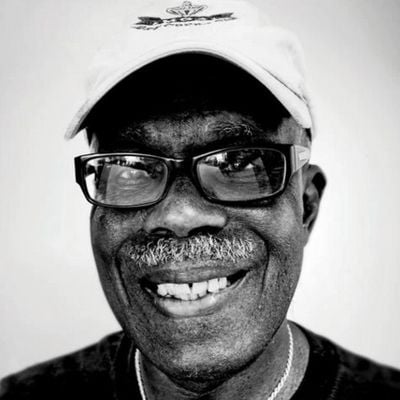

AFTS artist Larry Williams (Photo courtesy Art From the Streets)

Williams describes his artistic style as “primordial,” a word — and technique — he finally landed on after years of trial and error, he says. The subjects he paints include animals, landscapes, and jazz and African American themes. He’s influenced by the flourishes and curves of Japanese architecture. He loves to use bold colors. But most importantly, his artistic mantra comes from something he heard his mother tell her own art students many years ago: “Keep it simple, keep it simple.” Don’t tell the whole story to your audience, she would say. Let them draw their own conclusions.

Williams sums up his experience with AFTS and painting as a practice that gives him “stability, sobriety and a sense of entitlement,” as well as ownership over his life. Through AFTS he was able to sell enough art to be able to move into his own apartment five years ago, where he still lives today. He works part-time for the city and paints as much as possible; he tries to paint 30 new pieces a year.

“A lot of our artists have gotten off the streets because of our program,” says Pat Chapman, AFTS studio coordinator. Early on, the artists were only paid once a year for the art they sold at a big annual art show. Now, they’ve scaled the program to offer prints of original artwork as well as other merchandise, along with pop-ups and smaller shows throughout the year. This approach has provided many of the artists with consistent, livable income, Chapman says. They still have an annual art show at the Neal Kocurek Memorial Austin Convention Center, which can bring in upwards of $100,000, all of which is distributed to the artists.

Throughout history, many artists, particularly those who were women and people of color, would have been marginalized and impoverished had they not practiced their craft, and been paid for it. In the U.S., the estimated 567,000 people who are unsheltered or the more than 17 million living in extreme poverty have fallen through the gaps in our increasingly inadequate social safety net. Many have jobs but are not paid a liveable wage. They cannot afford the housing options in their area; they live in cars, tent camps, local shelters, or on the streets. Lack of affordable housing and inadequate income remain the leading causes of houselessness in the US, according to the National Law Center of Homelessness and Poverty.

Next City talked with artists who have had significant experience living with extreme economic hardship, or without shelter — how it shifted their perception of themselves and intersected with their own pre-held stigmas surrounding the unhoused — and ultimately, how it affected or catalyzed their art. For most, economic hardship and houselessness present varying degrees of financial, emotional and physical vulnerabilities, and their artistic expressions manifest that vulnerability. For some, art nurtures self-worth. For others art is a pathway to economic mobility. For most, their practice fosters a sense of home. In this feature, Next City explores how three artistic communities have been empowered and fulfilled through creative endeavors: Art From the Streets in Austin, MudGirls in Atlantic City and a conglomerate of artists and art organizations in the Skid Row neighborhood of Downtown Los Angeles.

Austin has experienced an 11 percent uptick in homelessness in 2020, including more than 1,500 who remain unsheltered. “Our homeless population is to an extreme point in Austin,” says Ruth Adams, the volunteer coordinator at AFTS.

The AFTS goal is to meet the artists where they are, and to help them “up, not out,” she says. The emphasis is on equitable access to art. AFTS gives them the tools and the space to uncover personal abilities and provides a platform to sell their art.

A work by AFTS artist Jesus Polanco (Photo courtesy of Art From the Streets)

“Our artists are part of our AFTS family and our first concerns are that we are serving them wisely and efficiently,” says Adams. “We meet our artists in their resiliency and move and adjust with them,” she says, echoing a sentiment voiced at a recent board meeting.

AFTS doesn’t fit into a pre-existing model or rubric, she says. They are unique both to the area, and nationwide, with a few exceptions.

“Throughout our history there have been people who, if not for their talent, would have been marginalized,” says John Trahar, recently named president of the board of directors. He was drawn to the program because of the almost instantaneous transformation of labels, from “homeless person,” to “artist.” The pervasive and misleading stereotypes of unsheltered people run deep in American consciousness, and the ability to de-stigmatize them through art is powerful, he says.

“[AFTS] provides this opportunity to and ability to interact with society in a way that generates positive feedback, both in terms of what they’ve created — through their own mind and skill — and then financially, [because] people like it well enough to pay for it,” he says. That feedback pays dividends far beyond the dollars earned, and the effect is visible. The program emphasizes self-determination theory, because focusing on housing alone doesn’t always mean sustaining a quality of life, he says.

Trahar’s main goals have been to scale up the program and revamp the website to make the platform more lucrative for the artists. Selling original pieces is difficult, he says. With the option of prints and shipping, the artists have more opportunities to grow their income; 95 percent of the proceeds go to the artists, with the remaining 5 percent covering shipping and packaging fees.

Before COVID-19, the AFTS studios were open at least four days a week for the artists to come and paint. On a busy day, between 18 and 35 regular artists will use the studio, though there have been up to 100 artists in the program at a time.

Throughout history, many artists, particularly those who were women and people of color, would have been marginalized and impoverished had they not practiced their craft and been paid for it.

Artwork by Rushdon; photo courtesy Art From the Streets

“The artists come in and they just hit it,” says Chapman. “They sit down and start painting. They’re gifted,” she says.

AFTS has brought in instructors on occasion, she says, but in general, the artists know what they want to do. Some, like John MacPherson, a classically trained artist, paint landscapes; other artists produce seascapes and rolling waves. Tom Jett prefers bold, whimsical landscapes. Chapman says after four years as the studio coordinator, she can look at a piece and name the artist.

“Some are trained artists,” she says. “Others just have a gift.”

The pandemic has been especially difficult on people living with homelessness. In Austin, which is in stage 5 of COVID-19 risk and recently hit a record high number of cases, the studios are closed indefinitely. Many AFTS artists rely on disability payments and government funding; some are still on the streets, says Chapman. Many were dependent on art sales.

“We’ve been trying to figure out how to keep them creative,” she says. “Without that community, some are not creating. We’re trying to do more online shows and more virtual stuff.”

Susan Privatera, a single mother of five, had moved to Atlantic City in 2017 and was working as a waitress when her van broke down. She lost her job as a result and was struggling financially. Through Haven-Beat the Streets Inc., a local transitional housing nonprofit, she heard there might be someone who could give her work and something to do while her children were in school.

When she arrived at St. Michael’s Church to meet Dorrie Papademetriou as instructed, she didn’t know the building housed a clay studio. The church was letting Papademetriou, along with some women from a day shelter, rent the rectory as a studio space. Privatera had never worked with clay.

“I looked around and thought — I don’t think I can do this,” she says. “But I wanted to try.”

Right then and there, Papademetriou suggested she take off her coat and try it out.

“Next thing I know, I’m her biggest clay maker,” says Privatera. “I’m actually really good at it. I always thought I didn’t have any talents — I can’t sing, or dance — but I’m really good at this.”

Susan Privatera, of MudGirls Studios (Photo by Dorrie Papademetriou)

MudGirls Studios was born in 2016 at the Marie Adelaide Center, or “Adelaide’s Place,” a day shelter for at-risk women living with homelessness in Atlantic City, where one out of every 2.5 residents face economic hardship.

Papademetriou is the founder of MudGirls and a graphic designer. She had been looking for a way to share her love of clay and the transformative power of creative expression. She began volunteering at Adelaide’s Place weekly. She brought chunks of unformed clay and started teaching the women to construct slab-built pieces, a method that uses smooth slices of clay that are then rolled, pressed and formed by hand.

The women looked forward to clay time. “It was just a break in their day,” says Papademetriou, “something they had never done before. We just started making.”

Little by little, the small group of women gathered steam, as participants wanted to try making new things such as sculptures, vases and bowls, she says. They began selling their wares at local fair trade markets, and demand grew.

Saint Michael’s Church offered MudGirls a permanent and affordable studio space in 2017, and Papdemetriou hired four particularly interested women, where they worked with clay daily. They became a ceramic art studio that creates and sells functional pottery and tablewares, as well as tiles and decorative items. Through continued outreach at Adelaide’s Place over the years, MudGirls initiated a job readiness program that employs at any one time 5 to 10 women between the ages of 18 and 60 as potters. Among the potters are single mothers, women struggling with mental health issues, addiction and depression, or young at-risk girls that need work experience for their resumes. Economic hardship, says Papademetreiou, is the main connection.

“[These women are] not only desperately impoverished and in need of a source of income, but [they] need to feel connected,” she says.

Privatera is one of the permanent claymakers and says she loves working in this medium more than anything else.

“There’s nothing I want to do besides work,” she says. “It’s very therapeutic.”

Hand-making clay is a precise process, she says. The clay must have the perfect texture. It needs to be prepared, rolled out and formed. It can then take one to three days to dry. After that, it’s fired in the kiln, glazed, and refired. Everything produced by MudGirls is a team effort.

Privatera says she takes pride in every piece she produces. Even if something is cracked, or comes out of the kiln with imperfections, she takes it home.

“It’s perfect to me,” she says. “When you take a piece of mud and it becomes this beautiful thing … it’s very pleasurable.”

The pandemic has affected her anxiety, she says. With her children in virtual school, Privatera is unable to go to the studio as often. Her oldest daughter recently returned home from prison after four years. The MudGirls team had a biweekly support group before the pandemic that can no longer meet. It’s all taken a toll.

For Privatera, the MudGirls are family. They often spend holidays together, and she hosted them for Christmas at her home in 2019. Papademetriou, she says, is more than an employer. She’s a friend and advocate.

“She’s like a fairy godmother to me,” says Privatera.

Papademetriou emphasizes that she is not a social worker, but she is connected to social agencies that she can direct the women to in times of crisis. She’s often assisted her employees with housing applications and has attended eviction hearings with them.

“There are multiple levels of trauma that go along with being homeless or having mental illness,” she says. The challenges are multifaceted and sustaining change in the long term is tough. A holistic approach to the studio is essential, she says.

From left to right, Tahja G., Elle G. and Mary Ann M. pack orders in MudGirls Studios. (Photo by Dorrie Papademetriou)

Many women currently or previously employed by MudGirls have been able to transition to housing stability because of the reliable income. A few graduated from behavior therapy courses. Taking ownership of their work and abilities, and taking an active role in the studio, has helped a number of these women meet the challenges they face, she says.

One employee, a woman with schizophrenia, is in charge of clay prep. All day she wedges and recycles it, which requires a lot of kneading, punching and pulling, says Papademetriou. These simple repetitive tasks can be transformative, she says.

“It’s physical, it’s focused, it’s malleable, it’s soft,” she says. “I think the biggest thing I see in [how it can] transform mood is that you can make something from nothing. From a piece of mud or clay. A piece of the earth. When you open the kiln their breath is taken away. ‘Like, oh my god, we made this’.”

One reason Papademetriou chose clay as the medium was because of its accessibility and physicality. Even if you’re not a trained potter, you can make something beautiful out of clay.

“In the studio, we create a sense of community and empowerment — the belief that making can affirm your existence,” she says. “When you produce something tangible it proves, ‘here I am.’”

The 55-block Skid Row neighborhood in downtown Los Angeles is a thriving arts scene, and home to 20,000 residents. It’s also a community that has been deeply under-resourced, subject to years of systemic oppression, devastated by COVID-19, and comprised predominantly of Black and low-income residents. The populace includes families, veterans, an active drug recovery community, individuals with mental and physical disabilities, and people returning from incarceration. In other words, it’s remarkably diverse.

Skid Row is not unique in its subjection to criminalization of poverty and homelessness, but it may well be unique in its resiliency and vibrancy.

More than 40 former flop-house hotels have been transformed by nonprofits to provide safe, affordable, permanent housing and this housing stock has been preserved in large part due to the organized civic engagement of Skid Row residents.

“Skid Row is a neighborhood that [fights] an existential battle on a daily basis,” says Hayk Makhmuryan, an art worker and activist in the neighborhood for 12 years, whose work centers equitable access to arts and art space. Because, according to a majority of outside voices, the neighborhood does not “exist,” and the residents are characterized as transients, even though more than 50 percent live in permanent housing.

“The narrative is often hijacked,” says Makhmuryan, “sometimes maliciously. Very often, what you hear in the press, or mainstream discourse is the viewpoint of a mission, or housing group. These are resources at best, but not resident voices,” he adds.

“When you produce something tangible it proves, ‘here I am.’”

Photo by Dorrie Papademetriou

Makhmuryan spends most of his time coordinating arts programs and working with the Skid Row Design Collective. He also runs Studio 526, where many residents sell their visual art. Last year he launched a newsletter, Doodles Without Borders, that discusses arts-related happenings in Skid Row and connects those developments to larger movements in the region.

He does not emphasize commodification of art in his work, although he does believe it’s important to support artists, who are chronically underpaid and undervalued for their work.

“There are people that have and do look to art and creative expression as a form of economic mobility, but the part that I think is important is that art is not the solution to homelessness, in the economic sense,” he says.

In marginalized and oppressed neighborhoods, populated predominantly by people of color, community-controlled gathering spaces such as cafes and parks — places taken for granted in wealthier neighborhoods — are rare or completely absent, Makhmuryan says. For example, Skid Row doesn’t have a branch of the L.A. public library.

“Because access to community spaces where people can come together in a non-prescribed kind of way is so scarce, art spaces can take on that role,” he says.

Los Angeles Poverty Department (LAPD), the first performance group and the first arts program composed entirely of houseless people, creates regular performances and public art to end negative stereotypes about people experiencing homelessness and to educate Angelenos about issues affecting the Skid Row community such as gentrification, mass incarceration, drug policy reform and the criminalization of poverty.

“We started doing very incremental performances, improv — where we’d act out the interior voice of a welfare worker and client. It was always really tied in with the people that fought to preserve the neighborhood,” says John Malpede, performer and activist who founded LAPD in 1985.

The group also offers art workshops which are facilitated by a group of artists who offer mentorship and support. The LAPD has won multiple awards for rethinking drug recovery programs and gentrification.

“We have a registry of artists in Skid Row. We always used community spaces as part of our survival strategy,” Malpede says. “We have a place now to defend the border and show history.”

Malpede emphasizes that economic mobility is not the aim. “We don’t prioritize selling artwork; [we are] more into activating art,” he says.

The Freedom Singers, a group led by Kayo Anderson, are part of LACAN's arts and culture branch. (Photo courtesy of Kayo Anderson/Los Angeles Community Action Network)

The idea of making a livelihood from art is “weird,” says Malpede. Many artists don’t make their living that way, especially not in Skid Row. Some LAPD members are also members of LA’s Screen Actors Guild, he says, and residents can make money from performances. But beating homelessness or becoming financially well-off is not a priority.

“The group is really turning upside down the notion of what you need in order to sustain yourself,” says Malpede. “And what it is to be recognized as a full person.”

Kayo Anderson, a current Skid Row resident, was a thriving artist his entire life. After studying Music Education and voice at Jackson State University, he founded the Mosaic Singers of the Mosaic Youth Theatre of Detroit, one of the most revered youth choirs in the country, performing for presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, and poet Maya Angelou. After moving to L.A., wanting to “break into the industry,” Anderson found himself suddenly houseless after falling ill in 2016.

“Getting sick changed my trajectory,” he says.

He found solace and community in Skid Row, and soon found work with a nonprofit called the Freedom Singers, composed of community members who are or were houseless and who have, in some way, used their art to “get themselves back,” he says.

Now, Anderson serves as the current minister of arts and culture in the Los Angeles Community Action Network (LA CAN), formed in 1999 to provide myriad services for Skid Row residents, in areas such as legal assistance, housing and civil rights. Anderson curates LA CAN’s weekly “culture hour,” featuring artists and performers with or without instruments that emphasize the African Diaspora through R&B, Reggae, Blues and other musical genres. He still oversees the Freedom Singers, a branch of the LA CAN arts and culture. Currently, the culture hour is virtual due to COVID-19.

He emphasizes excellence in his work, he says. “There’s a tendency to give out participation trophies,” he says. “Let’s build ourselves out without making excuses.”

Aside from his duties as minister, he works as a constant advocate for artists in Skid Row, organizing collectives and meetings to discuss their varying needs, and running a personal “hotline,” an art advocacy mutual aid emergency number that artists in the community can call at any time.

“Artists can call me and say ‘my saxophone needs repair,’ or ‘I haven’t eaten today’,” he says.

Anderson says it’s important that the public realize that very few people in Skid Row are living “sad lives,” despite what the media suggests. He believes that you’re more likely to find those “sad lives” in L.A.’s wealthier neighborhoods.

“Here in Skid Row, I could get ten people, without a house, to help me find something to eat,” he says. “That’s who we are as a society. Poor people give a lot more away. Recognition of that is really important.”

This article is part of “For Whom, By Whom,” a series of articles about how creative placemaking can expand opportunities for low-income people living in disinvested communities. This series is generously underwritten by the Kresge Foundation.

Claire Marie Porter was Next City’s INN/Columbia Journalism School intern for Fall 2020. She is a Pennsylvania-based journalist who writes about health, science, and environmental justice, and her work can be found in The Washington Post, Grid Magazine, WIRED and other publications.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine