On May 1, 2018, the workers' rights group Voces de la Frontera mobilized more than 10,000 people for the "Day without Latinx & Immigrants" march in Waukesha, a suburb of Milwaukee. Workers struck, and more than 100 businesses closed in solidarity.

Photo by Susan Ruggles

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberJenny Estrada lives in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, a small city on Lake Michigan surrounded by dairy farms. She’s a rural organizer for Voces de la Frontera, an immigrants’ rights organization based in Milwaukee. “Lots of these small towns recognize that immigrants grew the town out,” she explains. “They realize that without immigrants, the town would die.”

Still, for immigrants who see friends and neighbors picked up by ICE when they appear for court dates or who hear about raids on dairy farms, the situation is tense. “People are afraid. The fear is real that [deportations] are going to happen.”

Part of Estrada’s work involves recruiting and training rapid response teams who protest ICE when the agency raids a workplace or picks up someone without papers. Group members will also accompany people to court dates since ICE has been using those situations to detain people. This kind of initiative, she says, along with know-your-rights trainings, create a space for non-immigrant community members to get involved and show solidarity.

“We’ve seen an uptick in volunteers. People are starting to realize that this is everybody’s issue,” Estrada said. “Before there were groups that didn’t work with Voces even though they were working on the same issues because they saw us as too political. That’s changed.”

Estrada’s work means dealing with prejudice and racism. “There’s been so much crap in the media,” she says. “There is definitely a divide between urban and rural areas. People will say: ‘You guys are exaggerating.’”

But that didn’t prevent Estrada from filling 11 buses from rural areas north of Milwaukee. On May 1, the group and its partners converged on downtown Waukesha, a Milwaukee suburb. They mobilized some 10,000 people from rural counties and cities, including a number of Democratic gubernatorial contenders. Approximately 100 businesses closed in solidarity as well. Marchers demanded an end to the county sheriff’s collaboration with Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) 287(g) program.

Estrada is just one of the many people forging a visionary alliance between urban and rural workers — an alliance aimed at staving off federal intervention on farms and in cities. Voces has never been shy about using economic pressure to achieve its goals, and the power behind that pressure comes from its member-driven organizing decisions. In Wisconsin, “America’s Dairyland,” many dairy farms rely on immigrant labor to stay in business. Dairy farms generate $43 billion in annual economic activity, powering the state’s economy. This economic influence means that farmer — and farm worker — voices occupy a key space in state and local politics.

As Wisconsin has become a political battleground and a testing ground for conservative policies, Voces has worked to protect immigrants’ rights. At the same time, the group stresses how anti-immigrant measures divide and weaken the greater community. In the face of dehumanizing proposals, Voces has organized to empower workers and their allies to pull the economic levers that will influence policy.

Chief Russell Jack runs the police department in Waukesha, Wisconsin, and coordinated with Voces on the march. “Legally, the could’ve come to our city a day before the march and said, ‘Hey, just so you know, we’re marching tomorrow.’ That’s their constitutional right,” he says. “They didn’t. They came five weeks before the event and had multiple meetings with me and my supervisors and really worked with us in order to have a safe march.”

And while Jack says that he and Voces’ Executive Director, Christine Neumann-Ortiz, don’t see eye-to-eye on everything politically: “they were outstanding to work with as far as their cooperation.”

This kind of praise may seem odd coming from the head of a police department — often an organization seen as the adversary of immigrants and communities of color. But Voces has cultivated just such an organizing style to build support in a range of both rural and urban areas across Wisconsin.

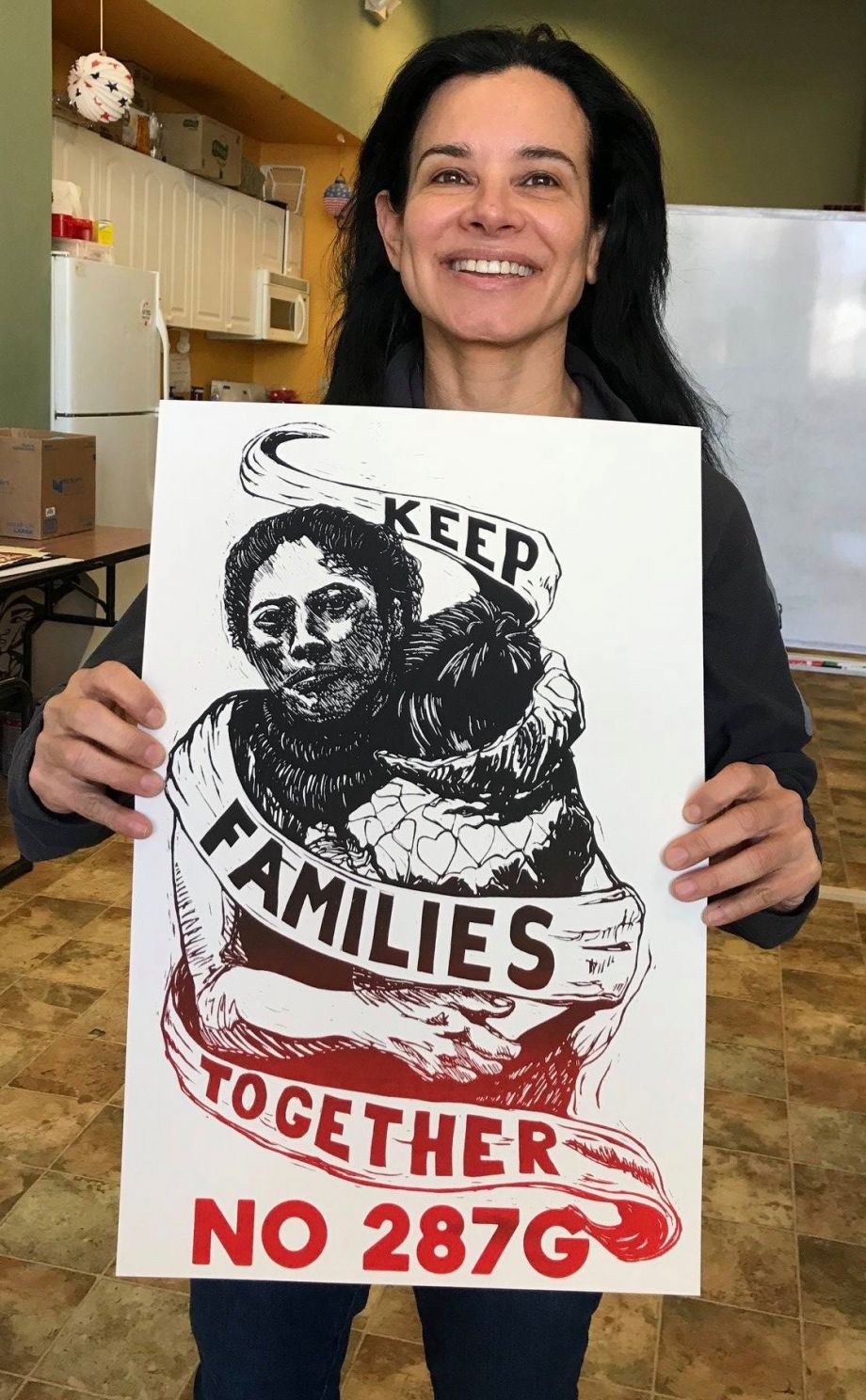

Voces de la Frontera Executive Director Christine Neumann-Ortiz holds a poster designed by Milwaukee artist Pete Railand. (Credit: Voces de la Frontera)

President Trump’s election galvanized the group to mobilize roughly 50,000 people in Milwaukee shortly after the inauguration for a march they called “A Day Without Latinos, Immigrants and Refugees.” Then, another 30,000 marched for International Workers’ Day, on May 1, 2017. These demonstrations were a counterpoint to steady and virulent anti-immigrant rhetoric and harsh policies emanating from the White House.

Neumann-Ortiz herself embodies the state’s German heritage and its growing Latino population; her father is German, and her mother is Mexican. The family moved around quite a bit during her childhood but lived in Milwaukee when Neumann-Ortiz attended elementary school. Years later, it was the place Neumann-Ortiz decided to make her home — and to grow Voces de la Frontera.

Since the state legislative session began last fall, Voces has battled both statewide anti-sanctuary bills and Section 287(g) plans in sheriff’s offices across Wisconsin. An amendment to the Immigration and Naturalization Act, 287(g) gives power to the federal government to deputize local law enforcement officials to act as immigration agents. As President Donald Trump and others have stoked anti-immigrant sentiment, cities and states around the country disagree on how to deal with immigrant populations. Jurisdictions that offer “sanctuary” to immigrants have been threatened with the loss of federal funding, even as the concept of sanctuary itself can be inconsistent and poorly defined from city to city.

Within days of taking office, Trump issued an executive order calling for local government participation in immigration enforcement under the 287(g) program. A memo from then-Department of Homeland Security Secretary (now Chief of Staff) John Kelly called 287(g) a “highly effective force multiplier,” and The Washington Post reported that Kelly “instructed his deputies to expand it ‘to the greatest extent practical.’” ICE’s website says that it currently has 287(g) agreements with 78 law enforcement agencies in 20 states.

In Wisconsin, Republicans in the state legislature introduced bills AB 190 and SB 275 last year; both would prohibit municipalities and counties from passing ordinances to opt out of cooperation with federal immigration authorities.

Still, even as Voces and its allies were fighting against these statewide anti-sanctuary bills, Waukesha County Sheriff Eric Severson signed a 287(g) agreement with ICE. The agreement stipulates that the Sheriff’s Office will cover the costs of the program.

Section 287(g) requires local law enforcement agencies to sign memoranda of agreement with the Department of Homeland Security. It also authorizes local law enforcement to issue “detainers” (requests) to hold immigrants for up to 48 hours after the charges that resulted in their detention have been resolved. Some attorneys and law enforcement officials are skeptical of the program’s legal underpinnings. The Major Cities Chiefs Association (MCCA) issued a press release in January 2017 criticizing President Trump’s executive order on sanctuary cities. The statement notes that federal courts have ruled: “that the ICE detainers referenced today do not provide sufficient legal justification for detention, arrest and incarceration by local officers.” The American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA) said in its report, “Cogs in the Deportation Machine:” “Courts have established that detainers are merely requests, and compliance cannot be mandated.” AILA also points to legal precedent for local liability when non-citizens have been held solely because of a detainer request.

Complicating matters further, some sheriff’s offices have agreements with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to receive payment for housing detainees. The Austin Statesman and other media outlets have argued that this can introduce a financial motive for local law enforcement to participate in immigration operations, even if immigration violations are civil and not criminal matters.

The Waukesha County Sheriff’s Office did not respond to several requests for an interview. ICE told Next City that the Waukesha County Sheriff’s Office does not have a pay-for-service agreement to house immigrant detainees.

Chief Jack does not oversee the Waukesha jail, nor does his department have any agreements with ICE. He runs the local police department, not the sheriff’s office. Jack also describes a decades-long relationship with the local Latino community center, La Casa de Esperanza. And while the police department’s Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) says that “immigration status is irrelevant with respect to Waukesha Police Department’s (WKPD) routine contacts,” Chief Jack says the department will contact ICE in certain cases — typically when violent crime is involved.

“I spoke to about 400 people at a forum, and I gave them copies of our SOPs in English and in Spanish,” Jack tells Next City. Voces de la Frontera and La Casa de Esperanza organized a forum in March that Jack and the Mayor of Waukesha attended. The chief asked the crowd: “Does anybody here, regardless of their immigration status, want people in the city of Waukesha who have been arrested for armed robbery, homicide, sexual assault of a child? And of course not.”

Although Jack presents seemingly clear-cut boundaries for his interactions with ICE, the real-world toll that policing takes on immigrants and communities of color is not so easily parsed. Research from the University of Illinois in Chicago has found that local law enforcement partnerships with ICE dissuade immigrants from reporting crimes. This, the study suggests, reduces public safety overall.

Likewise, while 287(g) originally targeted violent criminals, a 2011 report from the Migration Policy Institute found that, nationally, half of those targeted under 287(g) agreements had committed only misdemeanors or traffic violations.

The Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s 287(g) amendment to the Immigration and Naturalization Act authorizes local law enforcement to issue “detainers,” or requests, to hold immigrants for up to 48 hours after whatever charges that originally resulted in their detention have been resolved. Legal experts emphasize that compliance with these “detainers” cannot be mandated. (Photo by Susan Ruggles)

Eduardo Castro, a junior at a Milwaukee high school, shared his fears about the program with the crowd at the May 1 march in Waukesha.

“My father works around here in Waukesha and he’s been stopped three times before by a local law enforcement officer; and in one of those instances my father was threatened to get deported if he kept driving.”

Neumann-Ortiz says that Voces de la Frontera has gotten similar reports from others in the area as well.

“Driving without a license comes with a criminal charge, and if you get enough of those, you will be processed through the county court system or the county jail,” Neumann-Ortiz said. “The deputies in the jail that [the sheriff] is planning to deputize [as ICE agents], their primary function is to quickly identify who’s undocumented; process, get their information, look for someone who’s undocumented, and deport them,” she said.

Wisconsin now has one of the toughest driver’s license/photo ID requirements in the country, which has become a significant obstacle for the immigrant laborers who sustain Wisconsin’s dairy industry.

“They know the infrastructure needs to be built up for mass deportations,” Neumann-Ortiz tells Next City. “It happened under Obama. They’re quickly building it up and getting much more aggressive.”

A Department of Homeland Security investigation into law enforcement practices around 287(g) in Arizona and North Carolina found both racial profiling and unauthorized policing methods. Another report from the Center for Migration Studies determined that significantly higher numbers of Latinos were being arrested by a Maryland Sheriff’s Office “than would have occurred in the absence [of the 287(g) program].” Neumann-Ortiz says the “driving while Latino” anecdotes she’s heard confirm a similar phenomenon in Waukesha County.

Yet, for Neumann-Ortiz, the issue goes beyond a dragnet effect. “The part that is very clear is that this is lining up with the Trump agenda of discrimination and mass deportation,” she says. “Because their agenda has been to force local government to take on this role, and local law enforcement … So, for me it’s part of the Trump administration trying to test what they can get away with in terms of violation of constitutional rights.”

Julio Correa is one of the business owners who shut his doors in solidarity with the May 1 march. He runs a Mexican restaurant in the city of Waukesha. Correa is originally from Mexico and has lived in the U.S. since 1997, most of that time in Waukesha, where his brother lives. “It’s really calm here,” he said, and that makes it an attractive place to live.

In 2008, though, Correa spent 30 days in a detention center after being arrested. He ultimately won his case and has legal status in the US. Still, he says, “it was not fun at all.”

“I don’t have children, but I imagine what it would be like to go through [being separated from one’s children]. It’s really important to stand up and stop this program from passing.”

Jenny Estrada has no doubts about what she would do if the tables were turned. “Would I cross that river for a better life for my children? Absolutely. Five times.”

Nearby Milwaukee is one of the poorest and most segregated cities in the United States. It has also become one of the most polarized, surrounded by what are referred to as the conservative WOW counties — Waukesha, Ozaukee and Washington — that helped propel Scott Walker to the governor’s office in 2010. Milwaukee has a long history of civil rights struggles, and the state has the highest incarceration rate of Black men in the U.S.

In its 2006 march for immigrants’ rights, Neumann-Ortiz said Voces specifically chose to cross the Sixth Street Viaduct as a “shoutout” to the city’s civil rights history, referencing a famous 1967 NAACP Youth Council march that traversed the 16th Street Viaduct.

Echoing that sentiment was Mandela Barnes, a Democratic candidate for lieutenant governor, who attended the Voces annual meeting. A veteran community organizer with the faith-based group Micah, Barnes underscored the connections between Black and immigrant struggles.

“The same laws, the same mindset that make Wisconsin the number one incarcerator of Black males is the same mindset that gives us an anti-immigrant sentiment,” Barnes said.

Voces de la Frontera has approximately 1,500 dues-paying members, nine adult chapters and 15 youth chapters in schools. Neumann-Ortiz credits a ground-up, participatory organizing model as the basis for the group’s success. “We don’t do anything that the members don’t want to do,” she explained.

Months before Voces’ annual meeting in January, members discussed the possibility of a two-day strike among dairy workers. Cows must be milked twice daily, which makes the dairy industry a labor-intensive, seven-day-a-week commitment. Neumann-Ortiz believes a key factor in sinking the legislature’s anti-sanctuary AB 190 and SB 275 bills was the rumor that thousands of immigrant workers might abandon the state’s $50-billion industry for a strike.

At the annual meeting, Waukesha members decided to focus on organizing a one-day strike for May 1st. After the strategy sessions, Voces staff member Nancy Flores shared her own experience with the assembly.

“I know that the atmosphere in Waukesha is different from the atmosphere in Milwaukee because in Milwaukee there are lots of races, right?” Flores said. “I grew up in a town of 7,000 people where less than five percent of the population were not American. I know what it feels like. It’s like going up against a wave, right? So, I understand the members. My advice is: Don’t give up. In Walworth County, people need Voces. People need the fight.”

Voces funds its rural organizing work through a grant. That grant allowed them to hire Jenny Estrada, whose personal experience with immigration enforcement motivates her peripatetic campaign. Estrada is a white Wisconsin native. Her husband of 16 years, Jaime Martinez, was deported in 2012, although Estrada says it was because of a re-entry violation, and that he had never been charged with any criminal act. He had volunteered with the local YMCA and been an active member of the community.

“People rallied around me. They looked at him as a person and not as a demographic,” she explained, describing how many friends and neighbors had assumed that if he was married to a US citizen, then he must be a citizen, too. “This is your friend. It was eye-opening for people.”

After her husband’s deportation, Estrada followed him to Mexico with their children. It was a traumatic time for the family. “Three houses down from where we were, two ladies were decapitated. We had four small children.” So, Estrada returned to Manitowoc, and as the years and distance divided them, the couple grew apart and divorced.

The experience toughened her, and made her a passionate advocate. “I didn’t think I could cry any more,” Estrada says. But seeing Attorney General Jeff Sessions announce that the U.S. will separate children from their families, that made me cry.” She has no doubts what she would do if the tables were turned. “Would I cross that river for a better life for my children? Absolutely. Five times.”

Estrada asserts that not a single chief of police in the 35 small communities where she’s organizing supports programs such as 287(g). Requests for an interview with one of those chiefs went unanswered.

One of Estrada’s allies is Matthew Sauer, a Presbyterian pastor at the Manitowoc Cooperative Ministry. Sauer’s congregation spreads out over three churches; he shares the ministering responsibilities with Judine Duerwaechter, a United Church of Christ minister. Having grown up in Phoenix, Sauer says that as a young man, he witnessed both degrading treatment of immigrants and clergy who were arrested standing up for immigrants’ rights.

“In Wisconsin, [immigrants’ rights] wasn’t a big priority for many years,” he said. “Now, over the past few years, it’s come to the fore. Manitowoc is a big dairy community,” Sauer explains. Immigrant workers keep the farms running. “Our [congregation is] involved in building places of sanctuary and hope. We don’t ignore the law, but the first responsibility we have is to justice.”

The dairy industry injects $43 billion into Wisconsin's economy annually, giving its largely immigrant labor force significant economic bargaining power. (AP Photo/Morry Gash)

Sauer’s progressive positions have generated some pushback within the community, so he says he navigates relationships with care. “I know when to keep my mouth shut and do more listening than talking. Because I have been here enough, I know who to call upon after the fact to be able to say: ‘I heard this going on. Can we have a conversation about this?’”

Saving face is important in the community, Sauer explains, and so taking the time to speak with people can allow for change without calling people out. “If you can sit down and have a cup of coffee with them in their office or something, you’d be amazed at what can happen.”

This kind of approach has also allowed Voces de la Frontera to work with different groups while applying political and economic pressure. “Part of the whole process was that the initial step was quiet, and the threat was that we would go public,” Neumann-Ortiz says, describing how the group handled retaliation against workers who demonstrated for immigrants’ rights in 2006. Finding pressure points was critical.

“There was a tortilla chip factory where they had fired the workers and then they only took back the permanent workers; the temporary workers were excluded,” she says. “And through talking with [the workers] we found out that one of the largest purchasers of their product was a large local supermarket owned by an immigrant family that very much supports the fight for immigrant rights. And so, they were the ones who followed up with our call to the owners to say: ‘You should be bringing these folks back.’ And ‘this is a worthy cause, you should be supporting it.’ And they did. And all of those workers were reinstated. But it was … analyzing where was that potential leverage and alliances.”

Farmers in Wisconsin are well aware of the role that immigrant workers play in the dairy industry. The Wisconsin Farmers’ Union sent a representative, Nick Levendovsky, to Voces’ annual meeting. “The agriculture industry is an $88-billion industry, and it wouldn’t be that way without the help of immigrant labor,” he says. (The Wisconsin Dairy Business Association, a trade group, declined to comment for this article.)

Voces has also made deals with farmers. Neumann-Ortiz says the group has had a core of farmer advocates with a spectrum of political affiliations since 2007. As the state legislature debated measures in 2016 banning sanctuary cities and local IDs for undocumented immigrants, Voces planned A Day Without Latinxs and Immigrants strike. In one meeting, Voces representatives explained to a group of farmers what the legislation would entail and asked for their support. The farmers agreed, and the two groups worked out a compromise that enabled most workers to participate in the march while skeleton crews kept the farms going. In exchange, the farmers agreed to lobby their representatives against the anti-sanctuary bills. Those bills ultimately died.

“One of the dairy workers was saying how after this Day without Latinos and Immigrants in 2016, they more deeply understood the importance that they had, like they didn’t really appreciate their importance to the economy until that point,” Neumann-Ortiz says. Unlike what happened in the aftermath of previous marches, she says that as of mid-May, Voces had received no reports of retaliation against workers who participated in the May 1 strike.

Zoe Sullivan is a multimedia journalist and visual artist with experience on the U.S. Gulf Coast, Argentina, Brazil, and Kenya. Her radio work has appeared on outlets such as BBC, Marketplace, Radio France International, Free Speech Radio News and DW. Her writing has appeared on outlets such as The Guardian, Al Jazeera America and The Crisis.

Follow Zoe .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine