Earlier this year, President Biden called for electrifying the entire federal vehicle fleet — about 645,000 passenger cars, trucks and vans — putting the nation on track to a green energy transportation future.

General Motors followed shortly after by announcing plans to only produce all-electric vehicles (EVs) by 2035. Several other major automakers either plan or have already produced EV models, joining Tesla which has dominated the market for over a decade.

That’s the good news. The bad news? We need to find a way to pay for the repair and maintenance of our roads, bridges and public transit — which all rely in part on gas tax revenues — once we fully transition away from gas-powered vehicles.

Demand for EVs in the U.S. is expected to grow, accounting for a projected 7.6 percent of the passenger car market in 2026, up from just 1.2 percent in 2018. While new EVs are more expensive than conventional vehicles, prices will fall as they become less costly to produce. Federal and state governments also offer a range of consumer incentives such as tax credits, cash rebates and reduced registration fees to boost sales.

In addition to becoming more affordable to purchase, demand for EVs is certain to rise further as drivers become more aware of the money they could save on fuel and routine maintenance.

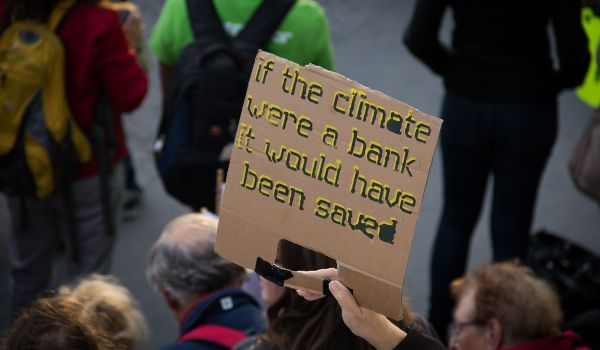

The growing demand for EVs and U.S. automakers’ production decisions may also reflect a shift in attitude on climate change among Americans. A Pew poll last year found that almost two-thirds of Americans said that protecting the environment should be a priority for the federal government compared to 41 percent in 2008. EV adoption will go a long way towards reducing environmentally harmful carbon emissions because transportation accounts for almost a third of the total, the largest share of any economic sector in the U.S.

But as more drivers ditch their combustion engine cars for the electric equivalent, concerns are rising that revenues in the Highway Trust Fund, a dedicated source of money from the federal gas tax charged at the pump, will further erode. Because the tax has not been raised since 1993 and fuel efficient vehicles have increased in popularity, there has been a growing gap between the money needed to maintain our roads and the amount raised through the Fund. Since 2008, Congress has had to rely on annual transfers from non-dedicated revenue sources to prevent the Highway Trust Fund from running out of money.

With the gas tax becoming more unreliable as a revenue source and EVs on the horizon, most experts now agree that something needs to be done: The question is what?

The simplest solution is to raise the gas tax, but this option is a political non-starter and doesn’t address the long-term question of greater EV dominance.

A carbon tax on greenhouse gas emissions, as some suggest, would likely raise substantial revenues and have far-reaching positive impacts on the climate. But a carbon tax aimed mostly at manufacturing facilities and power plants as now proposed, would act as a subsidy for car drivers since the cost effects would be indirect. It would also eliminate the user-pay principle that the gas tax was supposed to exemplify when it was created decades ago.

An increase in the corporate tax rate, as proposed in the American Jobs Plan to pay for new EV charging stations and other infrastructure priorities, lacks broad support and, if passed, would mean that drivers and non-drivers alike would end up paying; drivers would avoid paying their fair share to maintain the system.

There are some indications that Congress may phase out the Highway Trust Fund entirely. Proponents argue that using general fund revenues to pay for a transportation system that efficiently and safely moves people and goods is a wise investment and the returns will be realized over time. But before the federal government makes the choice to forgo the pay-as-you go funding system that’s been in place for almost 70 years — which it has the power to do — it may be wise to first explore other alternatives.

One innovative idea that could ensure a sustainable source of revenue is road user charges, also known as distance-based fees. It charges drivers for the number of miles they drive rather than the amount of gas used. In 2015, Oregon launched the first statewide, voluntary road user charge program, called OReGo, following two earlier successful pilot programs. Participants are charged 1.8 cents per mile and are allowed to choose which commercial vendor, of the three in the program, manages their accounts, as well as how their vehicle mileage is recorded. In exchange, those drivers receive credits for their fuel use, can save on their DMV registration fees, and may be able to skip emissions testing. The state legislature is now considering making the program mandatory in the near future, depending on how the debate over how the per-mile rate should vary by vehicle fuel efficiency is resolved. Following Oregon’s lead, a total of seven other states are now running their own pilot programs.

Beyond the revenue benefits, a national distance-based fee system makes sense because the technology already exists to put the system in place. Drivers would likely make fewer trips or take public transit as they become more aware of the true costs of driving, reducing traffic congestion. The system is also fair: the per-mile rate can be adjusted according to vehicle weight (commercial vehicles would pay more); time of day (vehicles during rush hour would also pay more); and location (driving within city limits would cost more).

Distance-based fees have never been seriously considered by the federal government even after two separate federal commissions published reports recommending that the federal gas tax be gradually replaced with distance-based fees. A University of Iowa study also demonstrated that it could work on a national scale.

The Administration had signaled a willingness early on to consider the concept but it ultimately was not included in the President’s infrastructure plan.

Given the President’s focus on building a twenty-first century infrastructure, the administration should now take the lead and establish a national per-mile user fee pilot program run by the USDOT. The recently passed $715 billion House version of the 5-year surface transportation bill (called the INVEST in America Act, H.R. 3684) directs the Administration to do that. The agency has been providing financial assistance to the states to help them set up their pilot programs, but the federal government should become much more involved to ensure an effective transition to a distance-based fee system.

The Administration has said that it wants to reduce the nation’s carbon footprint and build our infrastructure for the future. It needs to pursue innovative solutions that would do that.

Noel Popwell is a policy analyst with the New Jersey state government and an adjunct faculty member at the Rutgers University-Newark School of Public Affairs and Administration.

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)