The world is facing a housing crisis of monumental proportions: Over 1 billion people now live in slums, in makeshift homes that often lack even the most basic survival amenities. These self-built settlements have proliferated at a rapid pace due to a confluence of massive rural-to-urban migration and ad-hoc urban planning, particularly in developing countries. As a result, slums have become the only option for low-income families struggling to get by. If cities don’t address this need for affordable housing, the situation is only expected to get worse. By 2030, the number of slum dwellers is expected to double to 2 billion, an issue being taken up this week in Surabaya, Indonesia, at the final lead-up meeting before a global agreement on urbanization is voted on at Habitat III, the United Nations’ once-every-20-years conference on housing and sustainability.

But as drafts of that agreement — the New Urban Agenda — suggest, the world is in critical need of new solutions to tackle these growing issues for the world’s poor — and, increasingly, the task is being set in front of entities outside of government.

In recent years, architecture competitions have called on creative thinkers in their profession to resist the pull of shiny, new skyscrapers and instead, design answers to the housing problems facing the world’s fast-growing cities.

Two years ago, the Urban Design Research Institute (UDRI) in Mumbai, an independent organization advocating for more equitable development in its home city, held an international competition to redevelop Dharavi, one of Asia’s largest slums. The competition garnered innovative proposals from individuals and firms from more than 20 different countries. They ranged from bathroom towers that moonlight as public spaces, to new streetscapes, to a collective brand around products created in Dharavi. UDRI has since presented the winning ideas to the government to inject new life into a stalemate discussion on the future of the city’s slum upgrading.

Last year, Shelter Global, an international architecture nonprofit, launched a similar architecture competition — though this time on a global scale — called the Dencity Competition. The goal is to foster new ways of handling the growing density of unplanned cities. In the first year of the competition, the organization received over 350 projects from over 50 countries. This year, the organization asked competitors to “consider how design can empower communities and allow for a self sufficient future.” Shelter Global hopes the competition will gather a portfolio of new ideas while also increasing awareness around the state of housing and the need for innovation thinking to solve these issues.

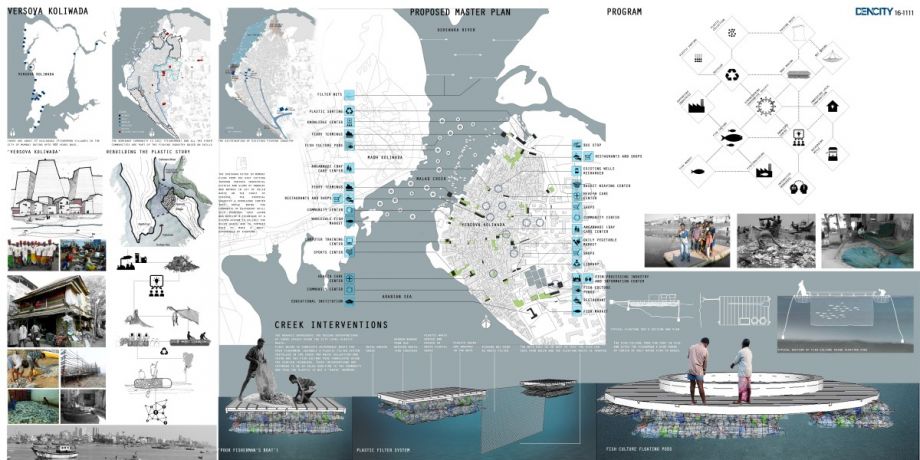

This year’s winning proposal addressed the needs of one of the coastal city of Mumbai’s oldest communities: the Kolis — native fisher people whose livelihoods and communities in the city are at stake. The project, called Versova Koliwada, was submitted by architects Jai Bhadgaonkar and Ketaki Tare from Mumbai, and looks critically at Versova Village, one of 27 Koli villages (called “Koliwadas”) dotting the peninsula city. The communities, many of which have relied on fishing as a livelihood for centuries, face an uncertain future due to a growing pollution issue that has had a devastating impact on the fishing industry.

Although the Versova Koliwada community lives in a village-style area in the massive metropolis, their lives and livelihoods are interconnected with the development and growth of the city. The industrial effluents and solid waste, especially plastic debris, that is dumped into water sources in the city have collected along the coast and had a harmful environmental impact. During monsoons, heaps of plastic garbage along the Mumbai coast can reach as high as 15 feet. Versova Koliwada’s unique position at the mouth of a local river and the Arabian Sea was once a breeding ground, but recently, fish mortality has increased and the Koli livelihood has suffered.

Bhadgaonkar and Tare’s unique intervention addresses the sustainability of this community and its future integration into the city. Their first step would be to establish a knowledge center to enhance the skills of the community and encourage new applications for the unused waste. Plastic bottles, they propose, could be creatively attached together with wooden boards atop to create floatation devices or, as they say, “poor man’s boats.” These floatation devices would put to use the plastic debris and positively impact the mangroves and coral in that area.

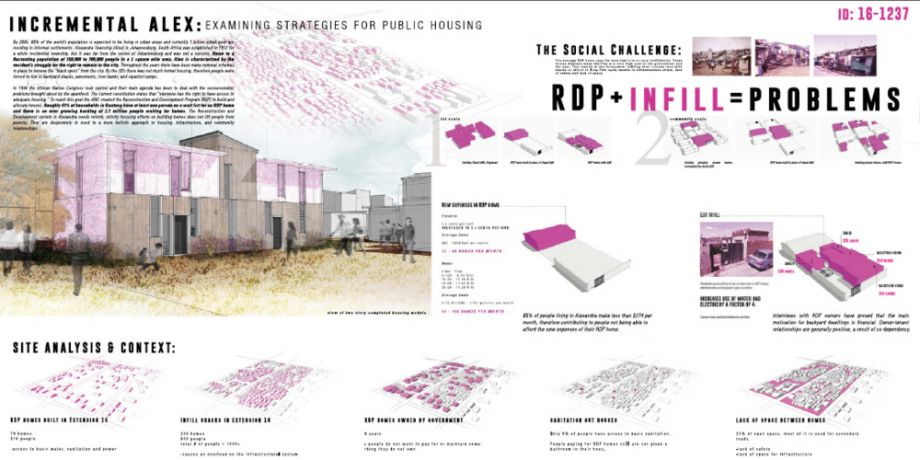

Dencity’s second place winner is Lauren Brosius, a recent graduate of Philadelphia University, who proposes to improve one of Johannesburg’s poorest areas, Alexandra Township. Her project, Incremental Alex, refocuses government-granted Reconstruction and Development Program (RDP) funding toward improving infrastructure in the neighborhood rather than just building homes. Brosius’s research revealed that residents are living in backyard shacks of RDP homes, which, her proposal says, “has proven to be a very positive, co-dependent relationship.” The backyard tenants provide extra income and security. “Backyard shacks paired with suitable infrastructure could be a solution to keep the density of the rest of Alexandra and diversify RDP housing. Currently the problem lies within the fact that RDP homes replace existing shacks at a much lower density and efficiency then what is necessary in Alexandra,” says Brosius’ proposal.

Jury member Julia King, who herself recently won an Emerging Woman Architect of the Year award for her innovative work on sanitation in Delhi slums, believes the project is a “very good analysis of a deprived and peripheral neighborhood combined with a sound proposal for how to incrementally develop housing.”

A Harvard team of Amira Abdel-Rahman, Gabriel Muñoz Moreno and Santiago Serna Gonzalez took home third place for their proposal to address ventilation in slums, a pressing public health issue in crowded, smoggy communities. They focus on retrofitting existing slums and improving their thermal performance through a sophisticated software analysis of climate metrics.

Shelter Global’s competition is a step towards gathering solutions to these most critical urban issues, an exercise in problem solving that demands the creativity of both urban practitioners and government officials. The UN-Habitat meetings happening this week in Surabaya offer a peek at what that could look like. The fate of 2 billion soon-to-be slum dwellers may very well hang in the balance.

Next City is covering preparations for the United Nations’ Habitat III conference in Quito, Ecuador, in October 2016, through reporting, op-eds and video. With grants from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Kresge Foundation and Ford Foundation, we’re covering the critical issues at stake on the road to creating a “New Urban Agenda.” In partnership with the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, we’re also co-producing a video series to capture the stakes and the stakeholders of this important once-every-two-decades event.

Carlin Carr is an urban development professional interested in innovative ideas for social change.