This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberJust for a second, Ron Bouganim takes the party line.

“If you’re a venture capitalist you’re going to tell your startup, ‘do not, do not, do not sell to government,’” he says. “‘It’s going to kill you.’”

The founder and managing partner of the $23 million Govtech Fund is, of course, a venture capitalist, and he’s looking for startups that do exactly that: build better technology tools for public agencies to buy. It is the first venture capital fund dedicated solely to government technology startups.

If, like me, you live well outside the so-called startup ecosystem, you might expect a VC and angel investor like Bouganim to be contrarian. After all, risk — venture — is in the title.

But Govtech Fund is a departure, even among those trained to see unexpected potential. Bouganim says he made 562 pitches to raise the fund (he calculates four a day for about 16 months). Before that, he recalls going to friends in the VC community and telling them they should invest in government technology. Carve out some money, he said, and he would act as an advisor — for free. He wouldn’t even charge them.

Their answer?

“It was always the same,” he recalls. “‘No, no, no.’”

It’s a Tuesday in December, and we’re meeting at Café La Boulange in San Francisco’s quiet Cole Valley neighborhood, close to Bouganim’s home. Dressed casually with slicked-back hair and narrow, clear-rimmed glasses, he channels nothing of the wild-eyed evangelist you’d expect to have recently emerged from 562 pitch meetings. He’s calm and articulate. He seems relatively well rested.

Before founding Govtech, Bouganim made his living as an angel investor and adviser, investing in startups, many of which innovated online tools for business management, including ShareThrough, PagerDuty, HelloSign and Close.io. He’s also co-founded or held an early-stage management title with a number of successful startups: Razz, CCI (sold to British Telecom) and Trymedia Systems (sold to Macrovision). Since 2010, he’s been what he calls “an uber volunteer” with San Francisco nonprofit Code for America, which pairs city officials and coders for tech projects with a civic slant. Alongside Abhi Nemani, who also used to work for Code for America (he’s now chief data officer for the City of Los Angeles), he helped launch the organization’s first accelerator. O’Reilly Media’s Tim O’Reilly, a CFA board member, author and legend in tech circles, now acts as an adviser to Govtech Fund.

In other words, Bouganim’s idea might sound a little crazy, but his track record isn’t.

He outlines the Fund’s three defining points:

First, government matters.

“We fundamentally believe that government is the connective tissue between citizens,” he says. “It is critically important therefore that it operates — you fill in the blanks — as efficiently, as responsibly, as caringly as possible.”

Second, government technology infrastructure is, in his polite words, “not the most modern” and in 2015, it needs to be. From time-sucking city websites that are basically the 2D equivalent of a trip to the DMV to the politically damaging recurring error messages of HealthCare.gov’s initial launch, it’s a system that’s failing taxpayers and public agencies alike.

“Think about government today being executed without technology — every single policy that government takes on needs technology to execute it,” he says. “You can debate healthcare for three administrations and 30 years, and then it literally came down to a website.”

Third, comes the capitalism.

He recites figures like memorized word problems. The 30 companies that comprise the Dow Jones Industrial Average employ more than six million people worldwide. The U.S. government, including federal, state and local agencies, employs three to four times that. It spends around $142 billion a year on IT infrastructure. It runs more than 90,000 agencies.

“When you sit back and start to think about government as an enterprise, it is 22 million employees, it is — literally, the amount spent by government is almost twice as big as the total market cap of the entire Dow Jones,” he says.

“I believe I’m investing in what will be billion-dollar companies.”

So why the definitive, resounding chorus of no? If government is indeed a massive market with a desperate need, why do the financial engines of Silicon Valley historically reject it?

The main reason you don’t see many startups contracting with government is the simplest one: speed. Their calendars just don’t sync up.

“With startups you’re always trying to do something that is very, very innovative, very, very disruptive to your industry and has a fast growth,” says Ragi Burhum, CEO of AmigoCloud.

AmigoCloud is one of four startups that Govtech Fund has invested in since its September launch — the others include MindMixer which builds online engagement platforms, SmartProcure, which helps public agencies buy goods and services, and SeamlessDocs, which facilitates PDF e-signatures.

“You can debate healthcare for three administrations and 30 years, and then it literally came down to a website.”

Seated at a table in the company’s small office, it’s apparent Burhum speaks from experience. Despite the downtown San Francisco building’s stately brick exterior, the space feels slapdash, like the company has barely had time to set up shop. Cloth cubicle partitions surround mismatched furniture, bookshelves and a folded-up scooter on the floor. The sparse walls are hung with an AmigoCloud banner, a poster of the Incredible Hulk and a whiteboard topped with the words “collect data.”

The company builds a mobile mapping platform. Their customer base is composed mainly of public agencies, which should be a natural fit. Burhum points out the eighth-story window to the busy street below to demonstrate that everything a city manages, “the fire hydrants, the parcels, the stoplights, the stop signs” all need to be mapped. Agencies can use AmigoCloud’s software to keep tabs on potential eco-hazards like mines and pipelines. At the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority, officials use it to track vehicles and observe ridership patterns.

But tech startups like AmigoCloud don’t usually contract with government agencies, and the reason, Burhum explains, is their rapid-growth model.

“That’s kind of like the opposite of what happens in government,” he says. “There’s a long sales cycle. The procurement process is very involved. It’s just the opposite of what you would expect from a startup. You’ll literally have a conversation, and they’ll say ‘Great, I love this, this works, I’ll put you in the budget cycle and we’ll talk in six months.’ For a startup, a week is a long time.”

Public procurement — which is basically government-speak for “buying things” — does tend to be a long, involved process. At the federal level, it’s governed by a 53-section code called the Federal Acquisition Regulation, or FAR. Municipalities don’t have one set of rules to determine how they buy products and services, but the process is usually RFP (request for proposal) driven. This means that the agency specifies what it wants and then puts out a call for bids. Massive consultancies like AECOM and Parsons Brinckerhoff, with their hundreds of offices and internal setup designed for government projects, are the typical respondents.

And culturally, government officials tend to like legacy vendors for a simple reason too: They’re familiar.

Jeff Rubenstein is the founder of SmartProcure, also financed by Govtech Fund. Essentially a giant search engine, SmartProcure displays thousands of government purchases with the aim of increasing market transparency and broadening agencies’ buying horizons. Rubenstein credits the idea to his own public sector background with the police department in Delray Beach, Florida.

“You remember that old old saying: ‘You never get fired for buying IBM,’” he recalls. “The theory is that it’s better to deal with established players and ones you know, because if you step out, there’s some level of risk.”

And that famous risk aversion — while it might clash with Uber-flavored notions of disruption and innovation — isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Donald Cohen is executive director of In the Public Interest, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank that researches issues of contracting and privatization.

“Contracting is really hard work,” he says, adding that the regulations and laws that make it so slow aren’t just bureaucratic red tape, but safeguards against over-spending and litigation, and reflective of a system driven by multiple stakeholders and interests, rather than one bottom line.

“This is democracy,” he says. “We do need protections.”

Still, however well intended, the marketplace’s cycles and strictures haven’t, historically, allowed tech startups to compete.

“The historic reality is that those bids take two to three years to work themselves out,” Bouganim says. “If you’re a startup and have limited resources, you’re not going to spend three years trying to win a contract.”

According to Burhum, investors understand this.

“Traditional VCs shy away from government because of those long cycles, and understandably so,” he says.

Bouganim, he says, is different.

“He realizes, like, hey a trillion dollars is being spent on this — it’s a huge, untapped market. As an investor or VC, if I were one, that’s where I would look. If everyone else shies away, that’s even better.”

But not everyone has shied away.

In the days since Bouganim first began dipping his toes in the government tech waters, several high-profile investors have financed similar startups. In May 2014, OpenGov, which helps public agencies access and share their financial data, announced a $15 million financing round led by VC heavyweights Andreessen Horowitz, which has funded the likes of Airbnb, Facebook, Groupon, Lyft, Pinterest and Twitter. In July, Captricity, a data capture tool in partnership with the FDA, announced a $10 million Series B round led by Atlas Ventures.

A representative for Andreessen Horowitz declined an interview for this story, but general partner Balaji Srinivasan told the New York Times last year that, much like Govtech Fund, the firm sees an opportunity in the public sector’s aging technology infrastructure.

“[W]e think we can do a lot there,” he said.

He’s looking for startups that, within the next five to seven years, will generate tens of millions in revenue.

For venture firms and startups alike, the gov-tech market is “an interesting opportunity that’s not without its challenges,” says Josh Lerner, a professor of investment banking at Harvard Business School.

He sees definite barriers in the federal procurement sphere, citing Beltway bandit-style relationships between legacy IT contractors and D.C. officials.

“A young, unproven company could find it very difficult to get in the door,” he says. More promising opportunity can be found, he says, in city and state markets. Many of them, after all, face similar IT needs, and software targeting them collectively could do very well.

Still, startups and the companies funding them probably won’t be seeing what Jon Sotsky with the Knight Foundation calls “hockey-stick-shaped” growth — the kind of rapid scale accomplished by some of the other consumer-facing companies in Andreessen Horowitz’s portfolio. Sotsky, whose organization has invested in several government tech startups including Captricity (Knight also provides funding to Next City,) echoes everyone else: Government procurement just, famously, takes time. But he says that it’s still potentially a very profitable sphere — and more investors are seeing that.

“The market’s so big,” he says. “Any time there’s a big market to disrupt, it’s the story of the arduous journey for the end game. That’s a very appealing story.”

And by many accounts, the market itself — slowness, barriers to entry and all — is also starting to change.

“A lot of governments are looking for ways to save money and not have these massive RFPs,” says Mark Hasebroock with Dundee Venture Capital, another of MindMixer’s investors, adding that he sees potential for quick and even steep returns on investment as more agencies find out about gov-tech and civic-tech tools.

Evidence of that change in government can be found in Nemani, the 26-year-old chief data officer for the City of Los Angeles.

Nemani came into L.A.’s city hall with a resume that includes both Code for America and Google. Mayor Eric Garcetti hired him last August in an effort to make good on a campaign promise to make the city’s government more data-driven, open and innovative. Nemani has spent the last six months working on Data.LACity.org, a massive experiment in digital transparency and he, at least, understands what’s unique about Govtech’s startups.

“Many of the technologies that are in place were designed years ago in the first wave of digital technology,” he says, referring to the public sector infrastructure he’s seen. Historically, it was customized and unique only to itself, he says — the logical conclusion of an RFP bid, where a policymaker put out the request and a tech contractor answered it.

But now, the Web 2.0 landscape is dominated by “software as a service,” or SaaS, which Nemani explains as “a common platform that multiple agencies can use.”

“The web world has a fundamental assumption that you build on a stack to create value,” says Jennifer Pahlka, the founder and executive director of Code for America, when I ask her to explain the difference. “The government world is based on the notion that everything is an enormous project that you start from scratch.”

She recalls an anecdote she heard before starting CFA, from a former Google executive contracted to work with Veterans Affairs.

“It was a $400 million dollar investment for basically a jobs page,” she says. “His metaphor — I still remember to this day — was ‘It’s as if you’re asked to get soldiers from New York to D.C. and your approach is to go source the iron to lay down the rails and build the engines and negotiate with the labor unions and essentially build a railroad from scratch instead of buying a couple of train tickets.’”

The U.S. government spends around $142 billion a year on IT infrastructure.

“We organize our cities as silos, right?” Nemani says. “One city does one thing, another does another thing….But at the end of the day, in many cases, they have common services like public safety and civic engagement. … Instead of building a custom solution for each you can build a scalable platform and solve a problem for multiple cities at the same time. That’s what’s exciting about the government technology startup market. [They’re] building reusable tools at a dramatically cheaper cost.”

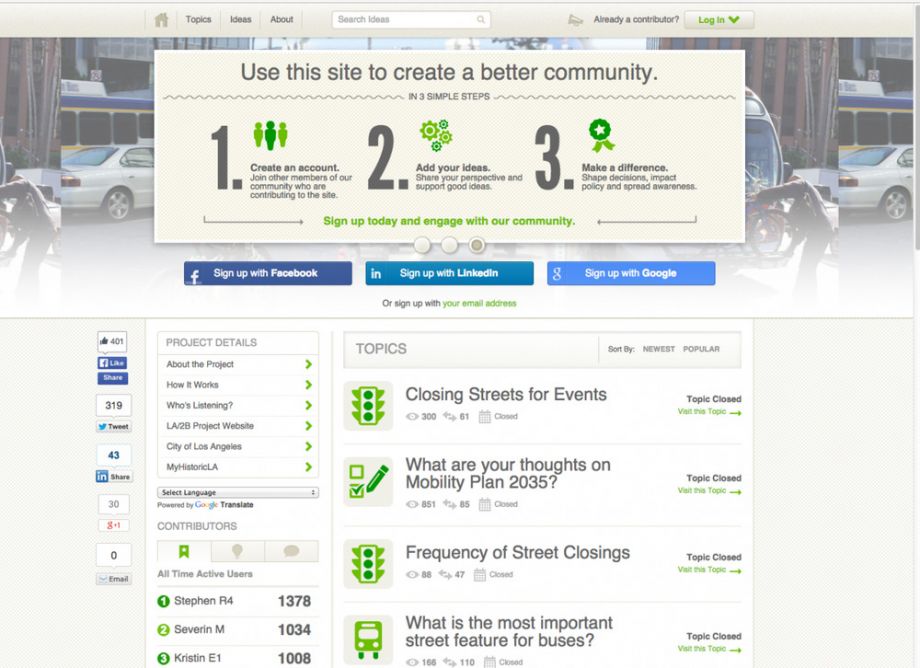

As an example, he cites MindMixer, another company Govtech Fund has financed. Residents can connect to the so-called “virtual town hall” through a number of entrances — Facebook, LinkedIn, email — and join discussion threads about transportation projects or regional plans. In the past, Los Angeles officials have used the platform to solicit input on the city’s transportation system, with questions as specific as “What is the most important street feature for buses?”

An online platform Mindmixer made for the Los Angeles Departments of City Planning and Transportation to engage citizens in thinking about mobility within the city.

The site’s mix of detail and simplicity comes from its co-founders’ urban planning backgrounds — “driving around going to public meetings that no one was showing up to,” as CEO Nick Bowden puts it. Govtech Fund was one of several investors to participate in MindMixer’s $17 million Series C round, which closed in September, when Bowden announced that the company would bring in up to 60 new employees by the year’s end.

“It’s a scalable solution that anybody can use and get feedback in a really smart, engaged way,” Nemani says.

“I ask if his two goals — bettering government and generating large amounts of money — ever conflict.”

When Bouganim talks about his market, he points to Nemani. Nearly a quarter of all public-sector employees will be retiring in the next five to ten years, he says. The people who replace them will be in Nemani’s generation, and they will undoubtedly be more comfortable than their predecessors with the kinds of cloud-based platforms he’s financing.

“[We’re going to see] a cultural revolution where the customer sitting on the other side of the table is actually very comfortable with startups,” Bouganim predicts.

For his part, Bouganim believes that government eventually will become a massive investment opportunity for other VCs. The reason: There’s a lot of software that needs to be fixed.

“I’m going to do this for the rest of my life,” he says.

Of course, he is unique in looking for a set of values-driven startups, which he outlines with a set of questions.

“When you are successful at scale, what kind of impact will you have on government? Will it be better, will it be more efficient, will it be more responsive, will it drive fluidity with citizens?” he asks. “The answer has to be ‘yes’ across the board.”

But he’s unapologetic about the profit motive.

“All venture investors are very similar. I’m looking for companies that have unique technology — mostly hardware, but software too — that have the ability to scale,” he says.

He explains what that means: He’s looking for startups that, within the next five to seven years, will generate tens of millions in revenue. Because the market is young, there aren’t a lot of examples, but he cites several older gov-tech companies like Palantir, valued at $10 billion and Socrata, which just announced a $30 million Series C round.

I ask if his two goals — bettering government and generating large amounts of money — ever conflict. After all, capitalism and the public good have a well-founded reputation for canceling each other out. And there’s no disguising the fact that both VCs and startups — however innovative, however well intentioned, however their ideas could radically transform the public sphere — are in it at least partly for the money. That’s their business model, fast growth, disruption and all.

Bouganim’s answer is simple: “If they do, I don’t invest.”

And that’s fair enough, but not every venture firm shares Govtech’s attitude toward government. Accurately or not, the tech community is often characterized by a brand of market-centric libertarianism that makes TV character Ron Swanson of “Parks and Recreation” look socialist. In 2013, a speech by Srinivasan (the Andreessen Horowitz partner quoted about the potential of gov-tech in the New York Times) came to symbolize this opt-out mentality; under the heading “Silicon Valley’s Ultimate Exit,” he pondered whether the U.S. had become “the Microsoft of nations” and urged his audience of startup founders to create tools, including tax shelters, that followed the broad legacy of Uber, Bitcoin and Airbnb — “all things that threaten D.C.’s power” and limit government’s hold on entrepreneurs.

Cohen, of In the Public Interest, advocates caution. “Government … has to serve the needs of every person and institution in this country,” he says. Regulatory reforms shouldn’t be undertaken “to meet the needs of business people, but to meet the needs of the American people.”

“The public purpose has to drive,” he adds.

For Bouganim, though, Govtech’s dual goals aren’t mutually exclusive. Admitting that he thinks of himself as neither idealist nor philanthropist, he predicts that each startup’s scale will simply follow its usefulness.

“I believe that the best companies … that will be the biggest and achieve the best scale are the companies that will deliver real value to the customer of government,” he says.

Hopefully he’s right.

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Rachel Dovey is an award-winning freelance writer and former USC Annenberg fellow living at the northern tip of California’s Bay Area. She writes about infrastructure, water and climate change and has been published by Bust, Wired, Paste, SF Weekly, the East Bay Express and the North Bay Bohemian

Follow Rachel .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine