When someone is experiencing a mental health crisis, the first response is often to call the police or emergency services. But tragedy after tragedy has shown that this can put the person at risk — especially if they belong to a marginalized group. The Treatment Advocacy Center’s research estimates that individuals with mental illness are 16 times more likely to be killed in police encounters than other civilians approached by law enforcement.

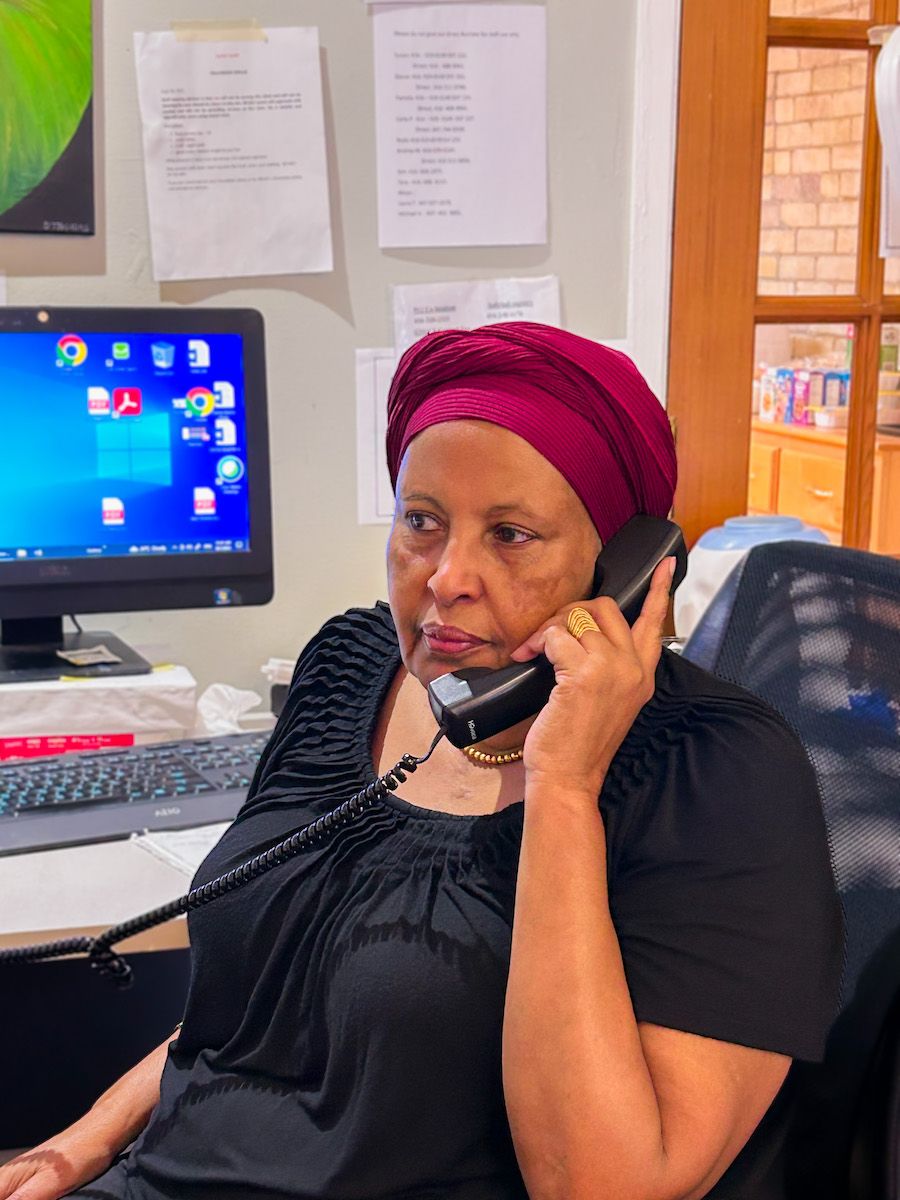

Kinsi, a Gerstein crisis worker, speaks to a caller on the crisis line. “Spending the time listening to callers is essential in allowing them to express what is going on for them from their

perspective,” Kinsi said. “When services are low-barrier and accessible, people can reach out when they need to, and they often reach out earlier in their crisis, allowing for more options in problem solving.” (Photo courtesy of Gerstein Crisis Centre)

But there are alternatives to a carceral approach to mental healthcare, according to a new case study released by Human Rights Watch in conjunction with Toronto’s Gerstein Crisis Centre.

As cities across North America struggle with homelessness and a substance abuse crisis, some cities are pursuing policies that force people with mental illness into treatment. In October, California officially launched CARE Court, a program that allows a third-party to petition the court to compel individuals with schizophrenia and related disorders to accept mental health treatment. And in New York City, Mayor Eric Adams has pursued a controversial policy of involuntary hospitalization for unhoused people with severe mental illness.

If there is a growing movement to remove people experiencing mental illness from public spaces, there is also a renewed push for non-coercive solutions that center the rights of the individual. Gerstein Crisis Centre’s model offers one alternative for how to support people experiencing mental health crises through a community-based mental health crisis response, rather than policing, involuntary hospitalization or forced treatment.

A rights-based, person-centered approach

After deinstitutionalization in Canada and the U.S., promised community mental health centers never materialized, leaving police, jails and hospitals as the primary response to people in crisis. Founded in 1989, the Gerstein Centre offers community-based services for people experiencing a mental health or substance use crisis. The organization currently employs about 100 people, most of whom have personal experience with mental illness or substance use.

The Gerstein Centre handles about 30,000 crisis calls every year and also offers a mobile crisis team, follow-up, referrals to other health and social services, crisis beds, and recovery and peer support programs. In 2021, Gerstein launched a pilot program that places crisis workers directly in 911 call centers. Mental health calls are diverted away from police dispatch to mental health intervention and support.

A Gerstein Crisis Centre Mobile Team pays a visit to an encampment for people without homes in Toronto. “Meeting people where they are located is a key component of creating access and connection,” says Elaine Amsterdam, the center’s crisis services director. “It is vital to work with an understanding that there are factors beyond diagnosis and symptoms that contribute to people being in crisis, like poverty, lack of housing, underemployment, racism, and discrimination.” (Photo

courtesy of Gerstein Crisis Centre)

Gerstein’s rights-based approach takes power dynamics into account — outreach workers wear normal clothes, for example, in an effort to destigmatize mental healthcare. Workers also start with the assumption that each client is an expert in their own life and recovery — that who a person is before and after the crisis is crucial to providing the right kind of treatment.

“They’ve got lots of skills and resources and knowledge that they may have gained over the years and all of that needs to be recognized and seen in the crisis,” says executive director Susan Davis.

Although Gerstein has been providing non-carceral solutions to mental health crises in Toronto for over 30 years, there is a new interest in alternatives to a police response.

“There’s a real hunger for solutions and a real willingness to think about these issues in an intersectional way,” says Olivia Ensign, senior advocate and researcher for the U.S. program of Human Rights Watch. “So it’s not just racial justice groups, it’s not just policing groups, it’s not just disability rights groups — it’s people thinking about and coming up with solutions in a holistic and intersectional way.”

As Davis points out, Toronto, with a population of about three million, is not a small city. Big cities have the opportunity to embrace a community-based model — but that paradigm shift can be a challenge.

“We have built a lot of our systems on a criminal justice response to a health issue, around mental health,” says Davis. “Nurses don’t want to go out without a police officer, social workers aren’t going to feel safe if they don’t have a police officer with them.”

Programs like Toronto’s were not created to solve the problem of people living outside with severe mental illnesses, says Davis. But early intervention that centers autonomy and social connection can help someone in crisis find the stability they need to get back on their feet.

“Instead of overloading an already overworked resource like the hospitals, the judiciary, the police, [these programs are] solving what is a personal health issue in a way that will support that person… getting to a point where they can find their way of being productive and participating in community and giving back,” says Baird.

Kaola Baird with teammates at the Dragon Boat Race Festival in 2021. (Photo by Samer Muscati / Human Rights Watch)

Connecting people to community

Kaola Baird felt like her life was “falling apart” when she sought services at Gerstein.

“Having a group of people or having somewhere to turn where you’re humanized… and you feel safe. For me, I always feel like I’m gonna get in trouble. So even when I’m not feeling well, somehow it’s my fault,” she says.

A fitness professional, she currently works for their peer support program.

“I know personally, they help you get grounded and stable. And then you could slowly start to work on whatever it is you need to get working on.”

Gerstein offers more than just a crisis line and access to services. It also helps people find social connection and support.

Kaola Baird with her cat on the balcony of her Toronto apartment. “I was lucky enough, when I

was at my lowest point, to have a place to reach out to get help and the support I needed,” she says. “There's a lot to be said for not wanting to be seen as your crisis, because there's still a person underneath.” (Photo by Samer Muscati / Human Rights Watch)

Gerstein founded FRESH, or Finding Recovery Through Exercise Skills and Hope, after a crisis worker noticed that many of the people who called the crisis line were experiencing loneliness and social isolation.

“We need pathways for people to make connection[s] and to build natural support networks that aren’t only just about seeing your case manager and your psychiatrist and the nurse twice a month,” says Davis.

FRESH is a peer-led program that connects people through group activities like hiking, yoga and music.

Baird currently works with FRESH. She also learned how to play the guitar through the program and started a band with fellow participants — a band that even got its first paying gig. FRESH has even expanded into four downtown locations at the Toronto Public Library.

It’s just one case study of how a mental health crisis program can be rooted in the needs of the community. But it helps illustrate the impact and scalability of such a model.

It’s powerful, says Baird, to be treated like a person with a past, present and future in a moment of crisis — to be more than just a diagnosis. Even today, years later, talking about it brings her to tears.

This story was produced through our Equitable Cities Fellowship for Social Impact Design, which is made possible with funding from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Maylin Tu is Next City's Equitable Cities Reporting Fellow for Social Impact Design. A freelance reporter based in Los Angeles, she writes about transportation and public infrastructure (especially bus shelters and bathrooms), with bylines in the Guardian, KCET, Next City, LAist, LA Public Press and JoySauce. She graduated with a BA in English from William Jewell College in Missouri.

Follow Maylin .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

Add to the Discussion

Next City sustaining members can comment on our stories. Keep the discussion going! Join our community of engaged members by donating today.

Already a sustaining member? Login here.