Design schools are places where form and function are taught extensively, and students learn to think in three-dimensions. They take complex problems, break them down into smaller parts, and display their design solutions through representation. Students are encouraged to interrogate their world and understand how it functions.

For decades, they learned that architects and designers were neutral characters who were mainly interested in improving society, even if that meant scarring cities with expressways and packing low-income residents in towers with no services nor access to employment. Thankfully, such modernist thinking gave way to a broader set of collaborative ideas that were better for cities and their people.

However, as broad as a design education can be today, it is still not broad enough, specifically when it comes to the built environment’s role in a society where systemic racism exists. That blind spot has always been obvious to design students and professionals of color. Then George Floyd was murdered, and it became undeniably obvious to all. That is when Dark Matter University (DMU) was started.

DMU is not an actual university. It is a democratic network of about 140 design academics and professionals, mostly Black, indigenous, and other people of color, interested in doing education differently. Their mission is to “create new forms of knowledge and knowledge production through radical anti-racist forms of communal knowledge and spatial practice that are grounded in lived experience.” The network is a way for new relationships between educators and institutions to form, in order to create new ways of teaching about the built environment.

By using their positions inside established programs, they hope to challenge, educate, and redefine design education so that more socially conscious graduates become the professionals of tomorrow.

The DMU network grew fast during the pandemic because of virtual meetings, as academics and professionals across North America collaborated. “If we seem really organized and seem really large, it’s because we’ve been meeting twice a week for almost a year,” explained Tya Winn, executive director at Community Design Collaborative in Philadelphia, during a webinar sharing the results from the first year of DMU’s existence. This network – which DMU calls its roster – benefits from the perspective of people from industrial design, sociology, urban planning, brand experience design, gender studies, historic preservation, race studies, and many other fields. The racial and intellectual diversity of the group gives DMU a more complete view of the built environment. “It’s one of the things that allows us to be interdisciplinary in our approach, but it also allows us to continue to learn, and continue to push ourselves to think differently,” said Winn.

In the past year, DMU has taught 14 courses across 15 institutions through educators who created or altered their courses to align with the network’s mission. Another benefit of these virtual times is that DMU established four cross-institutional courses, where students from different schools learned with each other from a roster of faculty members, and not one lecturer. Even graduate students are permitted to contribute content and create syllabi for courses, which has engaged students by using Instagram to reconceptualize how courses are introduced.

“One thing that we piloted this year was that we did video syllabi for our courses, which was something that students were really gravitating towards,” described Winn. “What starts as one studio becomes a partnership or a way for folks to work. Another project at another institution informs a course at three other institutions.”

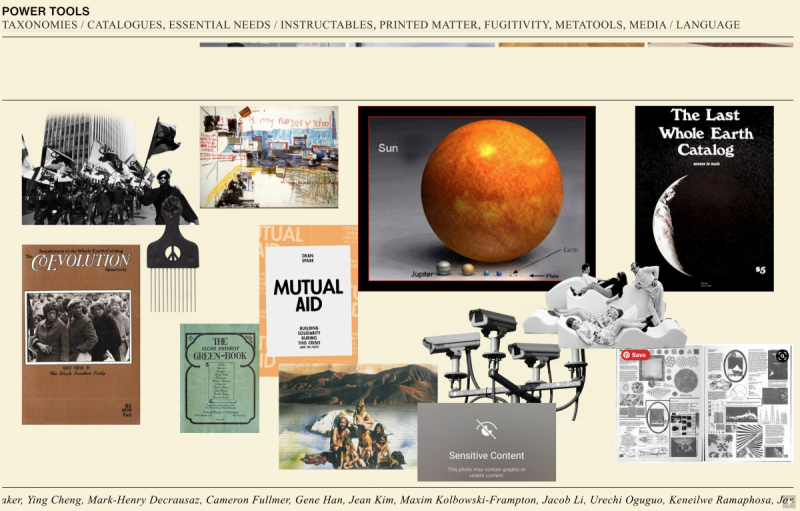

One new course that came into being through DMU is Power Tools, offered at Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. In it, students are asked to think about power structures and to design theoretical instruments that can be used by the community to challenge those structures. Taught by adjunct professors Lexi Tsien & Jelisa Blumberg, the way Power Tools was created is an example of the significance of DMU’s network to design education.

“I got involved in DMU because I was writing a letter to Yale – as an alum of Yale – demanding that they make a public statement about George Floyd,” Tsien tells Next City. “From that, I spoke with Justin Garrett Moore who was teaching at Yale, and he invited me to come to DMU.” Tsien and Blumberg met over the summer of 2020 while they were collaborating on building the DMU website. At the time, they were the only people in the network’s roster who had those skills. “It was very similar to Power Tools. We had to create something that would organize people, and through that we became friends.”

Although Columbia’s design programs teach students to think critically about the built environment – which most design programs do – this didn’t include racial equity, Tsien and Blumberg say. “There is an appetite for this kind of thing amongst students, and there isn’t enough representation of what activism means within the architectural space,” explains Tsien.

As they were creating a course catalog for DMU, they were inspired by the Whole Earth Catalog , a late 1960s American publication referenced in many design schools as an example of popular culture’s awakening to the importance of sustainable living and self-sufficiency. The educators saw the Whole Earth Catalog as having useful information with a history and legacy behind it, but not targeted to a diverse audience.

“We started by referencing a series of catalogs around the same time. The Whole Earth Catalog is a set of self-reliance tools, but we wanted to understand where the gaps were,” explained Blumberg. They wanted students to understand that design is not apolitical and that any position they take, no matter how harmless it may seem to them, is still a political statement. “I think sometimes in architectural fields we can almost render ourselves neutral, but that doesn’t mean that we are as neutral as we think we are in the built environment.”

When she and Tsien went to Columbia with their idea for Power Tools, the school was pleased to make this a graduate elective course.

“One of the strengths of this class was a strong sense of incidental collaboration,” says Mark-Henry Decrausaz, a graduate student who took the class. “A lot of us are friends and we talk about these things in class, which started to filter into some of our other classes and studios. That was unique. There is this ability for it to spin-off into practice, more than just instruction in a classroom environment.”

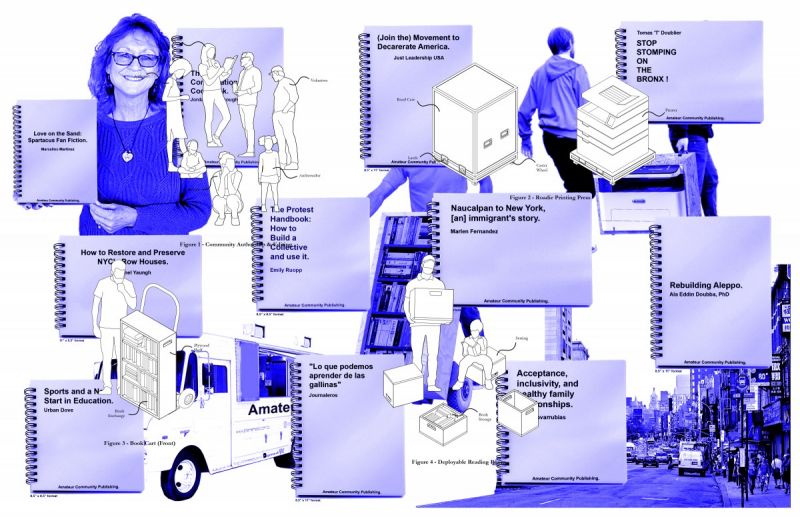

Decrausaz called his power tool Amateur Community Publishing, which would allow anyone in underserved communities access to traditional publishing. He believes it could be a mobile printing press, where anyone from a young child, to a senior, or a community activist can become a published author. By removing the gatekeepers of the publishing world, the ability to share knowledge through printed material is democratized and distributed on a massive scale.

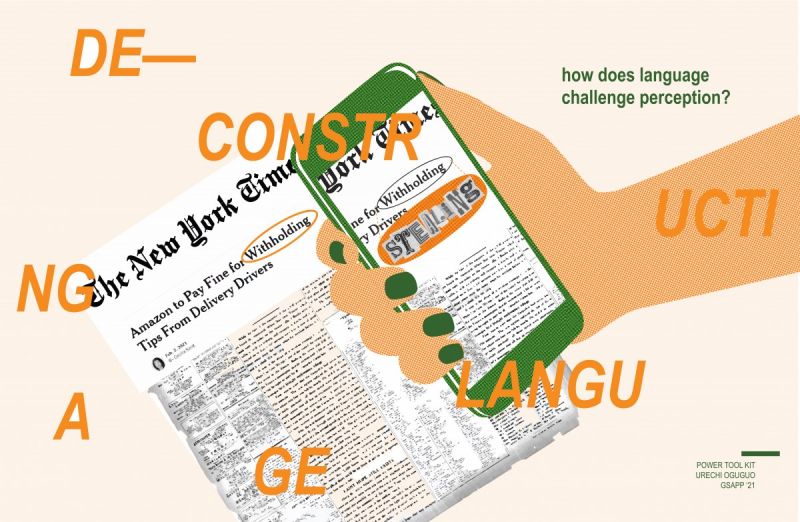

Urechi Oguguo, another graduate student who took the course, called her power tool Trutopia: an augmented reality application where activists can add messages to locations. Trutopia is only a theoretical tool that would allow users to circumvent traditional media and to create counternarratives that appear in real life in the public realm. The messages could also reveal truths about locations that aren’t publicly known. For example, users could mark-up locations with text to indicate where a sexual assault occurred, point out businesses not paying their employees a living wage, or critique advertisements on billboards.

Oguguo also thought about the consequences of such an app, and how it could be used for evil. “While having people tell their truths in shared AR space can be exciting, I understand that it can also be a source of abuse and misinformation. One idea I had was vetting users’ input for harassment or false information before it’s posted, but I also know that’s not enough, especially for this very ‘in-your-(AR) face’ app concept, she says.

Gallery: Additional Images from “Power Tools”

“The class was over before I could come up with a comfortable solution, although, I don’t think that my intention was to create a polished app or anything like that. I’m satisfied with how just sharing the idea for Trutopia itself worked as a tool to uncover the different layers of truths that inherently exist around us, whether we see/ hear/ chose to acknowledge them or not. Those already exist, Trutopia would have maybe helped visualize it.

Both students enjoyed how the course inverted the traditional method of architectural education that positions the designer as the one with agency deciding what the community needs. All of the power tools had a do-it-yourself aspect to them that allowed the community to build upon and expand what the designers created.

“We had a lot of other people from DMU who came to our class throughout the semester,” Blumberg recalls. “It’s been very exciting and there’s been so much support across the board for this type of class.”

“This (course) is collective knowledge for DMU as well,” said Tsien. “Other courses that are taught can cross-pollinate to create more opportunity and other kinds of investigations.”

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)