There are three natural enemies of urbanism: crime, terrorism, and pandemics. In the 1970s and 1980s, crime seemed like an existential threat to American cities. In the 2000s, it was terrorism. And today it’s pandemics, as COVID-19 sweeps across the country’s dense urban areas.

For many, all three cases provoke a fear of cities, especially the dense clustering of diverse populations. This fear can prevent decision-makers from understanding and implementing solutions to those problems. Fear can distort the market, leading public, private, and philanthropic sectors to fail to invest their money into the right places. And, of course, fear of cities feeds racism.

But looking at the real dynamics of crime, terrorism, and pandemics, we can see that, many times, this fear is misplaced. The actual relationship between urbanism and threats of crime, terrorism, and pandemics is not a straight and simple line — but the fundamental economic, social, and public health value of walkable urban places is clear.

The coronavirus is not an exclusively urban crisis

In the United States, New York City has by far the highest absolute number of COVID-19 cases. This has led many to conclude that the pandemic is primarily a big-city problem, and there are plenty of reports of inhabitants (especially wealthy ones) fleeing for less dense territory. Our colleagues Mark Muro, Jacob Whiton and Robert Maxim have noted the prevalence of COVID-19 cases in places such as New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago — urban counties that are the heart of the U.S. economy.

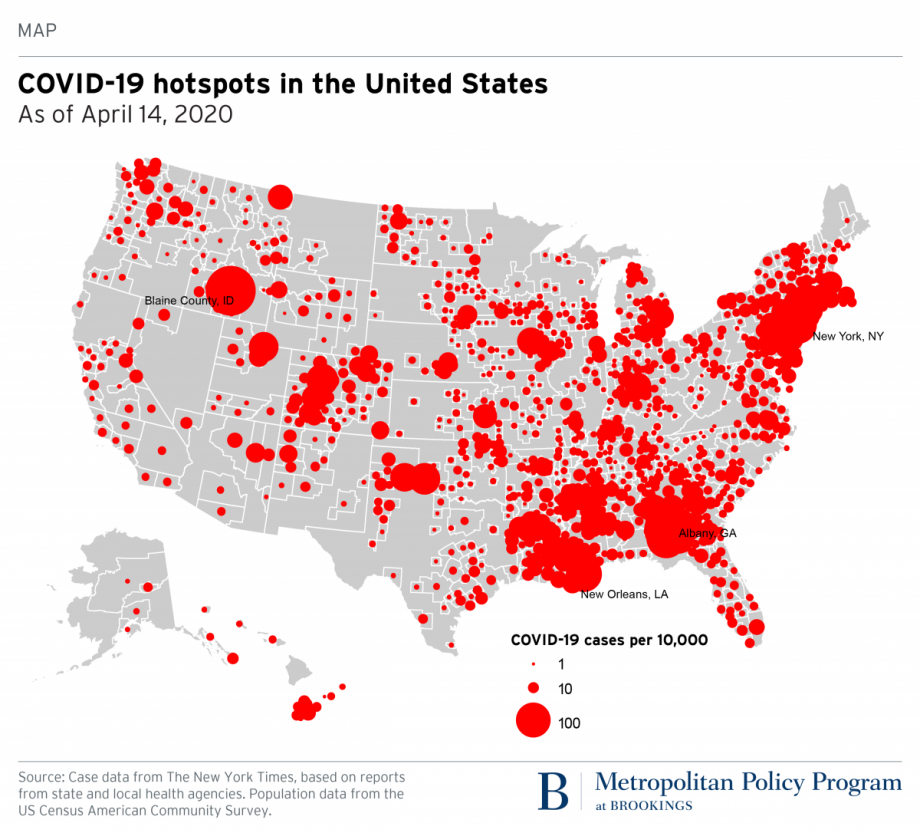

However, mapping cases per capita instead of by absolute number reveals a different story. Los Angeles and Chicago are simply places that have a lot of people, and thus more COVID-19 cases. The spread of the virus is driven by crowding behavior, not just density, which is why there have been major outbreaks in rural areas such as Blaine County, Idaho and Albany, Ga.

Rural areas are suffering relatively higher death rates from the virus as well, because their hospital systems are quickly overwhelmed and their populations are underinsured, older, and have more underlying health conditions. This is consistent with how the typical annual influenza affects the United States.

(Courtesy Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings)

Cities, suburbs, and rural areas can all be hit by COVID-19. Regardless of size or density, all places need to invest in the qualities that build resiliency. Strong regional economies built from local assets can creatively adapt to shifting demands. A flexible built environment that is green, walkable, and has low barriers to new and mixed land uses can reduce crowding and provide a platform for new businesses to launch and grow. And inclusive and civically organized neighborhoods can get the word out about public health measures, promote compliance, manage fear and support vulnerable individuals and businesses.

While fear of cities in regard to pandemics may be misplaced, the solutions to such crises can have a place everywhere.

Terrorism, cities, and recovery

When the Twin Towers collapsed on September 11, 2001, many people thought it meant the end of downtown New York. The very characteristics that distinguish urban places — economic growth, mass transit, walkable public spaces — are what attract those who want to terrorize.

Between 2000 and 2002, downtown Manhattan lost 5.6 percent (or 133,026) of its jobs. Office vacancy rates went from 5 percent (essentially fully leased) at $40 per square foot in the first quarter of 2001 to 13 percent vacant and $35 per square foot by the end of 2002. And although assigning value to any human life is a controversial subject, New York City’s Comptroller estimated that with the irreplaceable loss of 2,753 lives that day, between $83 billion and $95 billion was lost in combined people, GDP and capital.

Nevertheless, downtown Manhattan recovered. There were 22,961 residents in the Financial District in 2001, according to the Downtown Alliance — by 2008, that number had more than doubled. Today, office vacancy is below 8 percent and the going rate is $56 per square foot.

Terrorism did not destroy New York City. Fear of terrorism, however, continues to play a role in how many perceive cities, especially in light of urban diversity. President Trump and others have repeatedly linked immigrants and terrorism, stoking fears about foreign and new citizens within a urban context.

This fear blocks the reality of immigrants in cities: They are essential to the vitality of American cities, contributing one-third of the economic output of New York. Just as fear of urban pandemics prevents policymakers from implementing solutions that can help all places, fear of terrorism and immigrants blinds us from seeing the role diversity plays in economic recovery and expansion.

Fear of crime had a heavy cost

Long before September 11, a different kind of fear was echoing through American cities. The crime wave of the 1970s and 1980s had multiple intersecting causes, but it was undeniably an urban problem, with homicide rates far higher in cities, and even higher in larger cities.

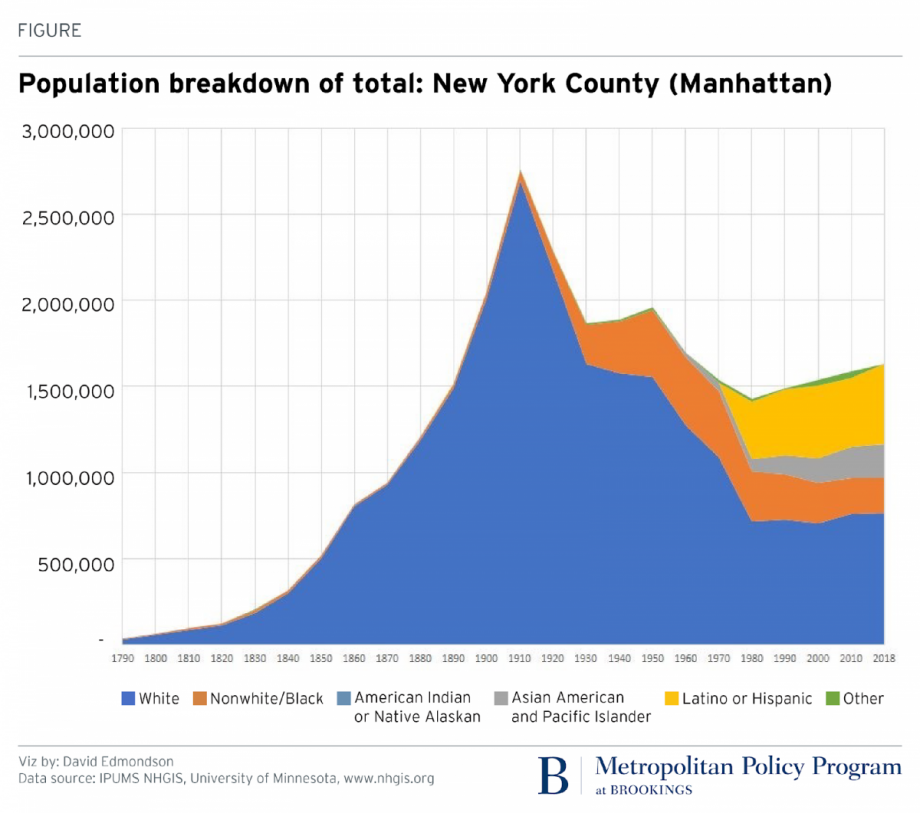

Downtowns hollowed out as employers left for the suburbs, storefronts were boarded up, and houses were left vacant. Manhattan alone lost over 500,000 residents, over a quarter of its total population, between 1950 and 1980. The vast majority of these departures were white residents heading for expanding suburbs created and kept racially segregated by a potent mix of land use law, homeowner covenants, and financing policy.

(Courtesy Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings)

But later, a combination of interventions brought about a historic decline in violent crime rates and a bull market on walkable urban places that even the Great Recession could not halt. All 30 of the largest metro areas in the country — representing 47 percent of the country’s population and 56 percent of our GDP — are experiencing unprecedented demand for residential and commercial space in neighborhoods that offer a walkable mix of land uses. As of 2018, demand for residential and commercial space in walkable places on average across these metro areas has grown 2.3 times the base market share in 2010. New construction can’t keep up, and prices have risen accordingly.

It is important to note that race-biased policies, such as stop-and-frisk, are not among the solutions that delivered this success. For many, the “urban problem” of crime pointed the finger at Black and Latino or Hispanic people. Fear of cities and their diverse inhabitants caused some urban leaders to pursue the wrong solutions, instead of embracing that diversity and the walkable, economically bountiful places city dwellers called home. The value of these cities has become plainly apparent — housing prices in New York City, for example, increased over 110 percent from 1996 to 2006. For decades, fear stymied and hid this value, at a cost to people both inside and outside America’s urban boundaries.

Run toward urban places

Fear of terrorism, of crime, and of racial integration helped create the suburbs. Will COVID-19 drive us there again? President Trump’s attempts to label the novel coronavirus the “Chinese virus” are just the latest in his long history of racialized attacks on cities. We can repeat past patterns of blaming cities’ close quarters and diverse populations for problems, or we can remove the blindfolds of fear and get to work on fighting this.

Walkable urban places have in the past — and most likely will in the future — proved to be extremely resilient in the face of crisis. Policymakers should sustain and feed this resiliency in urban areas and foster the same resiliency in suburban and rural places. COVID-19 is not the only crisis we are facing: Climate change, regional divergence, and our aging population also call for more transformative placemaking. The market is demanding more of these places to call home and to grow jobs. Centering our future growth in resilient places is required to stabilize and make sustainable state and local government budgets. We can’t let fear stop us from realizing these solutions.

Tracy Hadden Loh is a Fellow with the Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Center at the Brookings Institution. Christopher Leinberger is the Co-Founding Partner & Managing Director, Places Platform, LLC and Professor and Chair, Center for Real Estate & Urban Analysis, George Washington University School of Business.