San Francisco has a unique city department that most cities don’t have: the Department on the Status of Women. This department works to ensure that women and girls in the community have equal economic, social, political and educational opportunities, and helps to resolve issues that impact marginalized women and girls the most.

The mission of San Francisco’s Department on the Status of Women has included mediating discussions between the city’s sex workers and police — discussions that led to a simple policy that could save lives: amnesty for sex workers in the city who report violent crimes.

Sex workers — those who engage in consenting sex in exchange for money, as opposed to sex trafficking victims, who engage in non-consenting sex — often don’t report crimes, fearing that law enforcement officers will arrest them or take advantage of them, instead of investigating crimes they report. Their fears are not unwarranted.

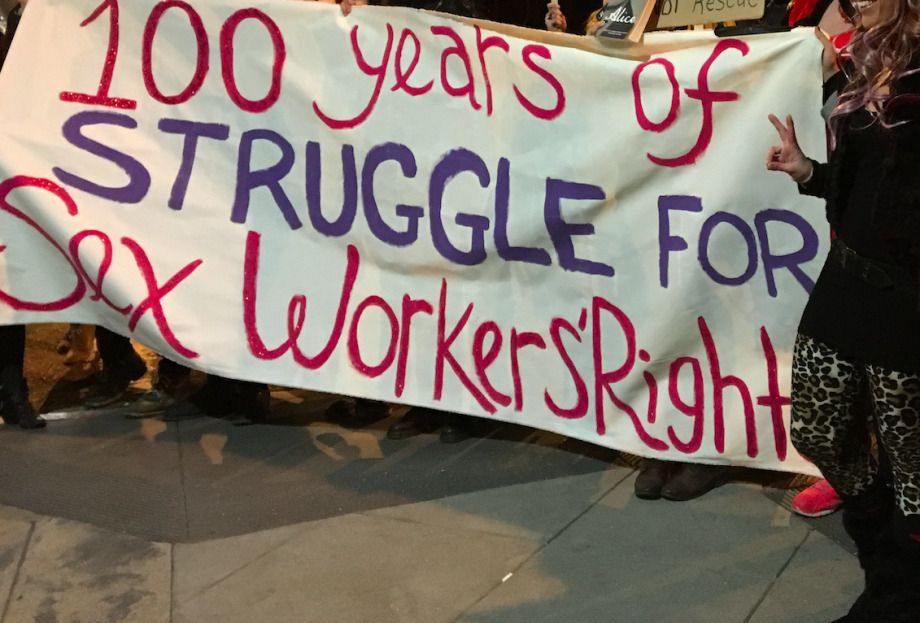

In the century since San Francisco criminalized prostitution, sex workers have consistently described the abuse carried out against them by men, including law enforcement officers. In 2016, as sex workers engaged in ongoing negotiations with the San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) and the District Attorney surrounding the amnesty policy, law enforcement agencies across the San Francisco Bay Area — including the San Francisco Police Department — found themselves deeply embroiled in a police sex scandal of seismic proportions.

At least two dozen Bay Area police officers allegedly had sex with an underage sex worker who went by the name of Celeste Guap. In 2016, Guap ran from a pimp on Oakland’s International Boulevard, approached a police car for help and met Oakland police Officer Brendan O’Brien. Investigations revealed that he was among the many officers who, instead of helping her, abused their positions of authority and used her for their own sexual pleasure.

Some Bay Area officers have had criminal charges filed against them and others have been fired. But many remain on the force, such as SFPD Officer Roger Ponce De Leon who was investigated in 2016 after Guap alleged that she had had sex with him. The SFPD paid him a salary of over $140,000 in 2017.

Sex workers and their advocates point to Guap’s experience as an all too common example of what goes on between sex workers and officers. As a result, an untold number of investigations never get off the ground, victims and witnesses never get interviewed by detectives and violent predators fail to be held accountable for their actions.

“Police take advantage of sex workers because they are illegal workers,” says Rachel West, a sex worker advocate in San Francisco.

West has championed decriminalization of sex work for decades and was among those who met with city officials to negotiate the amnesty policy.

The policy was the culmination of decades of sex workers’ advocacy, dating back to 1973, when the country’s first sex workers’ rights organization COYOTE (Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics), was founded in San Francisco.

The violence that sex workers endured in the city wasn’t thoroughly documented until the 1990s when the San Francisco Task Force on Prostitution was created. Around that time, discussions with the San Francisco Police Department about crafting a possible amnesty policy quickly deteriorated.

From 2014 to 2017, the San Francisco Department on the Status of Women formally mediated intensive discussions between the SFPD, sex workers and other community stakeholders. As a result, the San Francisco Police Department issued a first-of-its-kind, department-wide bulletin in December 2017 stating not only that sex workers reporting serious crimes would not face arrest, but that “…any officer misconduct against sex workers, including retaliation, coercion or coercive intimate acts, is subject to disciplinary and/or criminal action.”

“This historic legislation creates a path in California for sex workers to come forward and say, ‘me, too,’” said Minouche Kandel, Women’s Policy Director at the San Francisco Department on the Status of Women, following the passage of the policy.

“In my mind, this is a step toward better relationships with those in the city who are in charge and care about the well-being of sex workers,” says Carol Leigh, a San Francisco sex worker, activist and filmmaker, who helped craft the policy.

Leigh said that despite their exhaustive efforts, the policy still doesn’t ensure that sex workers with existing bench warrants — arrest warrants issued by a judge usually for failing to appear in court — will not be detained when they report crimes to law enforcement.

Momentum built quickly from there. Within weeks of San Francisco adopting its new policy, California Assemblymember Laura Friedman (D-Glendale) was inspired to introduce a piece of legislation expanding protections for sex workers reporting crimes statewide. Friedman said prior to hearing about the policy in San Francisco, she hadn’t known that sex workers were facing barriers to reporting crimes.

“It never occurred to me that people were being prosecuted when they came forward,” Friedman says. She spoke with advocates and district attorneys who confirmed the impact it was having on public safety.

Four months after Friedman crafted her bill, the California legislature passed it unanimously and Governor Jerry Brown signed it into law, in June.

Under the new law, which goes into effect in Jan. 2019, evidence that a victim or witness engaged in prostitution around the time that a violent crime occurred is no longer admissible. Friedman says this law will empower a vulnerable population to report crimes, which by extension, will improve safety in communities statewide.

“I think people really understood that it was a problem and that this could help get violent predators off the streets,” says Friedman.

Sex workers and advocates in San Francisco say the new California law is a huge step in the right direction, but they also say it doesn’t go far enough because it doesn’t grant them amnesty from arrest. Although sex workers who report violent crimes can no longer be prosecuted for prostitution under state law, they can still be arrested and held in jail.

Leigh says such arrests are disruptive, often derail lives and can lead to mothers losing custody of their children.

“For the legislature in California to do anything on the safety of sex workers is a breakthrough,” says West, who hopes legislators will introduce follow-up legislation more reflective of the new policy in San Francisco.

Unfortunately, as new protections for sex workers at the state and local levels emerge, sex worker advocates say new federal laws passed in April known as FOSTA-SESTA or the “Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act” and the “Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act” undermine those protections, despite their titles.

FOSTA-SESTA, aimed at combating sex trafficking, gives the federal government the right to prosecute websites that facilitate the sale of sex, regardless of whether it is consensual or not. It conflates non-consensual, non-voluntary sex trafficking with consensual, voluntary sex work.

As a result, sex workers across the United States are being driven further underground and offline, losing the protections that came from finding clients online, running background checks on them and then meeting them indoors, as opposed to on the street. Critics of FOSTA-SESTA also say sex trafficking victims may become harder to find, as online platforms often provided clues for investigators looking for missing persons.

As more sex workers are now resorting to streetwalking and the dangers that come with it, local and state laws that encourage them to report violent crimes may become even more important.

Hannah Albarazi is a San Francisco-based journalist who covers public safety, politics, business and law. She has written for CBS, Salon, and MIT Technology Review, among other news outlets.

Follow Hannah .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)