The Community Reinvestment Act was born in Chicago.

“The federal CRA was inspired by a response to redlining and the systematic refusal of financial services to Black residents [in Chicago],” says Illinois State Senator Jacqueline Collins, who recently spearheaded the passage of legislation to strengthen anti-redlining rules in her state. Since 2003 she’s represented the district that includes the predominantly Black neighborhoods on the South Side of Chicago where she grew up and still lives today.

Collins and her family moved from McComb, Mississippi to Chicago in the early 1950s. She was just a child. They were part of the Great Migration — six million Black people who fled the Jim Crow south, starting around the turn of the 20th century. An estimated 500,000 of them moved into Chicago. By 1970, there were one million Black people living in the Windy City — one third of the city’s population.

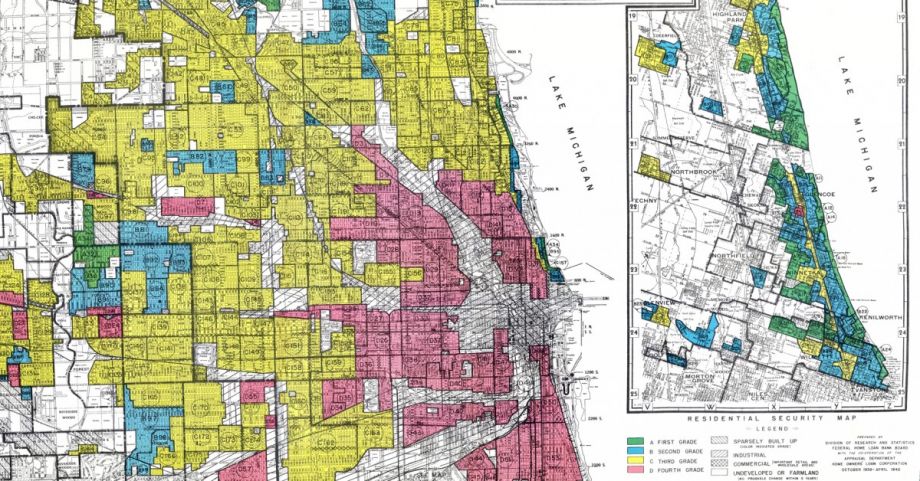

At first, local realtors and brokers restricted new Black residents to the city’s infamous “Black Belt,” a narrow strip from 12th Street to 79th Street, with its eastern border along Cottage Grove Avenue and western border at Wentworth Avenue. But gradually, and often in the face of violent resistance from new white neighbors, Black families found ways to move into other areas on the south and west sides of the city.

As Black families moved into those areas, federally-subsidized loans enabled white families to purchase homes in whites-only suburbs, and the banks mostly left with them. Collins marks the chapters of the story with street names as the borders expanded westward.

“[Discriminatory] tactics were used to prevent Blacks from moving beyond certain streets as barriers,” Collins says. “First Halsted, then Ashland, then Western. My family was one of the first Black families in the area I live in now, Auburn-Gresham.”

In the 1970s, a multi-racial coalition of community organizers led by Gail Cincotta, from the west side of Chicago, called for new laws to hold banks accountable for leaving certain communities behind. They pushed for passage of the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act in 1975, requiring lenders to disclose demographic and other data for each home mortgage to federal regulators, and to make that data available to the public. And in 1977, they pushed for the passage of the federal CRA, which says banks have an obligation to meet the credit needs of all the communities where they take deposits.

Since its passage, the federal CRA has helped incentivized banks to make more loans available than they otherwise might in low-to-moderate income neighborhoods, but it’s still fallen short of its original promise. Data available because of the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act show racial disparities persist in home mortgage lending patterns, yet more than 98 percent of banks get a passing grade when federal regulators examine them for compliance with the CRA. And these days, most home mortgages come from credit unions and mortgage companies, neither of which are subject to the CRA at the federal level.

But now, for the first time in Illinois, mortgage companies and certain credit unions are subject to standards for community reinvestment just like banks. As chair of the State Senate’s Committee on Financial Institutions, Collins spearheaded the passage of an expansive new state-based Community Reinvestment Act, covering state-chartered credit unions and most mortgage companies. According to state regulators, around 300 state-chartered banks, 190 state-chartered credit unions, and 500-600 mortgage companies licensed to operate in Illinois are now subject to the new law.

Only a few other states have their own CRA laws. Generally, state CRA laws and regulations hew closely to federal reinvestment policies and standards, but provide an extra layer of oversight. New York has one that applies to state-chartered banks. Connecticut’s CRA law extends to state-chartered credit unions. Massachusetts is the only other state with a CRA law that applies to state-chartered banks and credit unions as well as mortgage companies licensed to operate in the state.

Meanwhile, Federal Reserve Chairperson Jerome Powell recently voiced his support for expanding the federal CRA to all institutions that make consumer loans. “Like activities should have like regulation,” Powell said last week to the annual conference of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, a nationwide network of community development and fair housing groups. It would take legislative action from Congress to do so.

“A lot of the predatory practices fall within mortgage companies, not that the others aren’t culpable, but the mortgage companies have been able to forever skirt oversight,” Collins says.

Not all mortgage companies are the same, but as a group, mortgage companies have a sordid history in Chicago.

When the banks left neighborhoods because they were turning Black, predatory mortgage companies swooped in, and with them the practice of predatory contract sales — essentially lease-to-own agreements with large down payments, high monthly installment payments and no transfer of deed until the agreements were paid off in full. As documented in Ta-Nehisi Coates’ now seminal work “The Case for Reparations,” companies could and did often evict contract buyers for being late on a payment, leaving the buyer with no equity, and no home.

Black families in Chicago lost between $3 billion and $4 billion in wealth because of predatory housing contracts during the 1950s and 1960s, according to a 2019 study from researchers at Duke University, Loyola University Chicago and the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Community organizing in response to racial injustice was also behind the push for the new Illinois state CRA law.

First there was the pandemic, which hit Black Chicago harder than the rest of the city. Then there was the murder of George Floyd by then-police officer Derek Chauvin, which sparked uprisings across the country against continued anti-Black police brutality, uprisings that in Chicago were met with some dystopian tactics that hadn’t been deployed in decades.

Then, in June of last year, using data available because of the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act, an epic report from local WBEZ public radio showed stark racial disparities in home mortgage lending. Among the findings, mortgage companies like Quicken Loans/Rocket Mortgage were now making the majority of home mortgages in Chicago. And, from 2012-2018, banks, credit unions and mortgage companies collectively made more home loans in one majority-white neighborhood than in all majority-Black neighborhoods across Chicago combined.

All the above and the uprisings around them moved legislators to take action.

“Once I had the WBEZ study in front of me, I called for a hearing to address the issue, only two of nine banks invited testified, and only one provided oral testimony that day,” says Collins, who at the time was chairperson of the State Senate’s Committee on Financial Institutions. “But everyone else I’m sure was listening that day.”

It was during that hearing in October 2020 that the idea of creating a state-based CRA law first came to Collins’ attention, when Chasse Rehwinkel brought it up during his testimony. Rehwinkel is acting director of the division of banking at the Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation, the state agency responsible for chartering, licensing and regulating financial institutions in the state.

“These have been issues that have been brewing for a long time,” Rehwinkel says. “At our agency we’ve really wanted to take a good look at how to address some of those problems. There isn’t a panacea to that, but what are some tools? We saw this as one tool we could add.”

Around the same time of that hearing, the Illinois Black Caucus of State Legislators was forming its policy agenda, proposing a sweeping package of legislation touching everything from criminal justice reform and police accountability, to education and workforce development, health care and human services, and economic policy. The new state-based CRA got folded into the mix — along with a new 36 percent interest rate cap on consumer loans. It all passed this January.

“We had to move with the momentum after George Floyd’s assassination,” says Collins. “I don’t think the individual bills could have been passed on their own.”

The speed at which the package passed surprised even community development and fair housing groups.

“There was really a demand, on all levels of government, local state and federal elected officials representing Illinois, wanting to do something to address this problem,” says Brent Adams, senior vice president of policy and communications at the Woodstock Institute, a bank watchdog group based in Chicago.

For most of the previous four years, community development and fair housing groups across Illinois had been working in coalition to push back against the Trump Administration’s attempt to gut regulations around the federal CRA, which they feared would make it even easier for banks to pass their periodic CRA examinations — and also make it harder for communities to get banks to meet their credit needs. After the idea of a state-based CRA emerged at the October 2020 hearing, Woodstock Institute and others like Housing Action Illinois pivoted quickly into providing input on the proposed Illinois CRA.

“Some people think because we have fair housing laws now and important anti-discrimination laws on the books, that has rectified all the historical injustices,” says Sharon Legenza, executive director of Housing Action Illinois. “But what we see is it’s not translating as robustly as we need it to be. I think that’s where the Illinois CRA comes in, because we need more tools.”

One of the big issues that community development and fair housing groups have had with CRA regulations at the federal level has been the role of community voices in shaping what it means to be “meeting the credit needs” of the communities where lenders do business.

For years, bank lobbyists have sought consistency and clarity as to what counts for compliance with the federal CRA — home mortgages, small business loans, investments in community facilities, and so on. Banks tend to want a checklist — and that is essentially what the nation’s top bank regulatory agency, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, created in its recent overhaul of federal CRA regulations. But opponents of that approach say that it cuts out the voice of communities from the process of determining community credit needs.

“This notion of a list of things to do that qualify for CRA credit flies in the face of the law,” says Frank Woodruff, executive director of the National Alliance of Community Economic Development Associations. “There’s a strong scent of ‘urban renewal’ there if the federal regulators are telling banks what to do in communities.”

The Illinois state-based CRA does contain a list of factors that state regulators will consider under Illinois’ new CRA law, but at the top of the list is, “activities to ascertain the financial services needs of the community, including communication with community members regarding the financial services provided.”

“It’s no accident,” says Adams, of the bank watchdog group. “From a practitioner’s standpoint, I have found the ‘community’ part of the CRA is woefully lacking, and in some cases an afterthought. There’s no way to know what the community wants without asking the community and having them tell you. It’s painfully obvious.”

At its core, the idea is to give lenders more incentive to build and maintain healthy relationships with neighborhoods they’ve historically left behind or preyed upon. Similar to the federal CRA, the Illinois state-based CRA gives state regulators the power to consider CRA performance whenever a financial institution needs their approval. For banks, that could be any time they want to merge or acquire another bank, or open or close a branch. Mortgage companies have to renew their licenses on an annual basis. A poor state-based CRA record could lead to a denial of any of these actions.

Now that the law is in place, Illinois state regulators are reaching out to community groups as well as banks, credit unions and mortgage companies and also regulators in other states like Massachusetts to create a framework to implement the new state-based CRA — procedures, processes, and also training for regulatory examiners.

“It has to be workable for the regulated entity,” says Legenza. “It doesn’t mean they can’t be pushed a little bit out of their comfort zone, but if it something that is truly not workable, that’s something we’ll need to address.”

This article is part of The Bottom Line, a series exploring scalable solutions for problems related to affordability, inclusive economic growth and access to capital. Click here to subscribe to our Bottom Line newsletter.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)