The Armitage-Halsted historic district in Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood is renowned for its well-preserved collection of 19th-century architecture and commercial streetscapes, filled with Victoria-era ornamentation, pressed metal bays, and classic Chicago corner turrets. Today, Lincoln Park is a thoroughly gentrified site of winners-circle complacency; dog parks, stroller moms in yoga pants, tapas restaurants, and organic body waxing shops. But well within living memory, Lincoln Park was the site of a violent civil rights struggle for self-determination. In the late 1960s, Lincoln Park was rocked by firebombings, murder, and massive demographic displacement, inspiring a legacy of resistance that was one of the first to be erased from city’s civil rights history.

But it’s being unearthed in a walking tour from the National Public Housing Museum (NPHM) and Blu Rhythm Collective, a Chicago-based dance and arts group: The first in a series, “Stories from the Red Line—Lincoln Park: Fire Fire Gentrifier” tells this story of through the people that lived there and academics that have studied this struggle.

Underlying this story is the realization that Lincoln Park’s affluence came at a steep cost. “The story of Lincoln Park is one that is repressed all the time,” says Lisa Lee, executive director of the NPHM. “We don’t like to think that Lincoln Park was anything other than this amazing space of privilege.”

The walking tour uses the Vamonde mobile app to play audio files and show off period photographs by Lincoln Park native Carlos Flores, who also shares his experiences. (The Vamode website also presents the same materials for a virtual walking tour.) The tour begins at the site of the former McCormick Theological Seminary, now part of the DePaul School of Music, a neighborhood institution that local activists occupied because its generally progressive reputation made it likelier to accede to their demands.

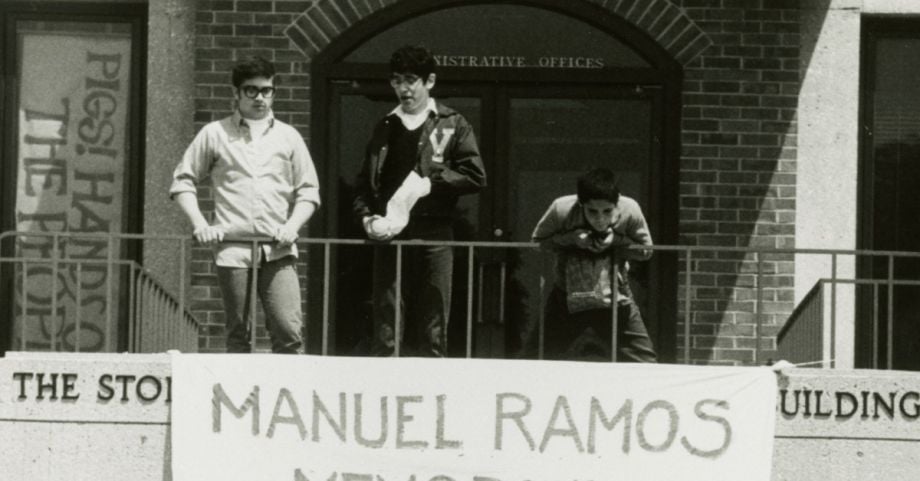

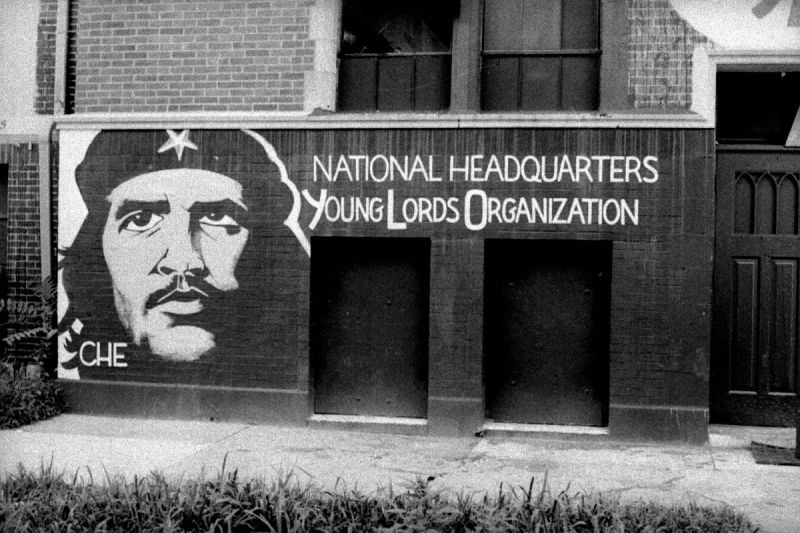

In the 1950s and 60s, Lincoln Park became a prized location for middle-class white professionals to settle in the city instead of adding to the suburban exodus, putting pressure on the poor, working-class white populations in the east of Lincoln Park, and slowly creeping westward, where many Puerto Ricans lived. In 1969, Jose “Cha Cha” Jimenez led a group of 350 people in occupying the seminary, renaming it the “Manuel Ramos Memorial Building,” after a compatriot that was murdered while unarmed by police. Jimenez was a leader of the Young Lords, a former Puerto Rican street gang that he transitioned into a political organization. The Young Lords demanded that the seminary fund affordable housing, health clinics, law offices, and more. After a week of occupation, the seminary granted their demands, worth about $4.2 million in today’s dollars. Jimenez was only 20 years old.

The next spot on the walking tour is the former site of the People’s Church at Armitage and Dayton. At what was the Armitage Avenue Methodist Church, Jimenez and the Young Lords established a healthcare clinic, daycare center, cultural center, and a free breakfast program, inspired by Black Panther Party, with the cooperation of the Reverend Bruce Johnson. The People’s Church was a powerful physical manifestation of the alliances the Young Lords had cemented with other radical activists like the Panthers and the Young Patriots, a group of poor Appalachian whites, in the Rainbow Coalition. But it wouldn’t last. Johnson and his wife Eugenia were stabbed to death in September of 1969; the church was demolished. Today it’s the site of an upscale Walgreens.

Gallery: Lincoln Park in the 1960s and 1970s

Lincoln Park native Carlos Flores's photographs show the neighborhood in the 1960s and 1970s, worlds away from the neighborhood today.

Monuments to the Puerto Rican community’s presence in Lincoln Park have been “intentionally and violently omitted,” says Jaqueline Lazu, a professor at DePaul who has studied the Young Lords’ political organizing extensively, and lends commentary on the walking tour. As a counter-example, Lazu talks about the next part of the city Chicago’s Puerto Ricans called home, after they were displaced from Lincoln Park as they’d been displaced many times before. (Jimenez moved nine times as a child.) Once in the West Side neighborhood of Humboldt Park, “they literally planted their flag,” she says, with a steel Puerto Rican flag spanning Division Street.

The last stop on the tour is at Lincoln Park High School, which encompasses one bit of Young Lords history that hasn’t been erased. It was where the Young Lords were founded in 1959, in opposition to established Polish and Italian gangs. (Early on, the Young Lords proved their mettle by scrapping with the school wrestling team). Built in 1900 in an ornately columned Greek Revival style that recalled the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, it fits in perfectly with today’s gentrified Lincoln Park, but for much of its history it was derided as hopelessly dysfunctional. The tour concludes with a video of Puerto Rican Rapper Pinqy Ring’s song “Victory” which recaps this history of Puerto Rican displacement and solidarity in Chicago.

Civil rights and gentrification histories are often assumed to be entirely about race, but the Young Lords story (and the alliances they forged in the Rainbow Coalition) shows that it’s also an issue of class.

Puerto Ricans didn’t arrive en masse to Lincoln Park until gentrification was already underway, and when they arrived they found themselves in a multi-ethnic place with Appalachian migrants, Black people, and poor, ethnic whites. “[Their] ideas could only have been incubated in a space like Lincoln Park, where you had all these different people of different backgrounds, only united by this attack from the state, and their own class consciousness,” says Lazu.

In The Battle of Lincoln Park, Daniel Kay Hertz examines how grassroots organizations founded to remake their neighborhood by and for middle-class white professionals fractured and broke after coming into contact with the Young Lords’ calls for self-determination and equity. The Lincoln Park Conservation Association (LPCA) began as a group of individual rehabbers working together to guard against what they saw as the creeping blight infecting neighborhoods surrounding Chicago’s Loop, but a key implicit function was also to keep people of color away from their gentrifying corridors. By the mid-60s, the LPCA began to fracture, as some members realized their actions were irrevocably changing the neighborhood, forcing out some their most vulnerable neighbors, and draining the place of the cultural vitality that originally attracted them. Meanwhile, federal and local police stepped up scrutiny of Jimenez, arresting him numerous times. A few weeks before Johnson was murdered, two Lincoln Park aldermen had their offices firebombed. In December 1969, the People’s Church was firebombed, on the same night that police assassinated Illinois Black Panther’s Party Chairman Fred Hampton.

Still, the Young Lords tried to work within the system, pitching their own affordable housing project, but were vetoed by Chicago’s Department of Urban Renewal. All told, 38,000 people were likely pushed out of Lincoln Park at this time.

In her role at the NPHM, Lee is interested in exploring how housing intersects with other social and economic measures of equity, and that’s a lesson echoed in the history of the Young Lords and Rainbow Coalition, who tied housing advocacy to free breakfast programs and healthcare. “They did such critical work linking housing to things like policing and public education, and public health,” she says. “That movement has so much to teach us about how you can and should be organizing, because the splintering of these movements is actually the success of neoliberalism, capitalism, [and] white supremacy.” It’s a template that’s been repeated with success in Chicago, when the Chicago Teacher’s Union focused a strike, which they won, on demands for more school nurses.

Rainbow Coalition organizers in Lincoln Park were able to recognize that though classism and racism were inflicted on disparate populations through different methods, the end result was the same. On Chicago’s South Side, for example, urban renewal often took a very different form than it did in Lincoln Park, displacing Black Chicagoans through wholesale destruction of neighborhoods that were then redeveloped into public housing towers. However, homes purchased on contract on the South and West Sides (where the purchaser—often a Black family without access to traditional mortgages—could have their home repossessed if they missed a single payment) still encouraged the same sort of granular, house-by-house displacement seen up north. “There was a natural understanding that the problems in the communities were basically the same,” says Billy “Che” Brooks, a Black Panther who organized with Jimenez in Lincoln Park, and lends his voice to the walking tour.

For the Panthers, this point of view was explicitly socialist; an outgrowth of their Ten Point Program. The point of organizing across racial lines was to “understand the importance of class struggle,” says Brooks. The free breakfast program was a way to introduce themselves to the community and start a conversation about a “socialist framework.” Espoused by the Panthers and other civil rights thinkers, the role of socialism in the Civil Rights movement is often one of the first things edited out of the historical narrative, like the Puerto Rican struggle for equitable development in Lincoln Park. “It’s important that oppressed people understand the economic situation that they’re in, and look at racism for what is it,” he says. “It’s a byproduct of the economic systems that allow divisions to come into play based on your skin color,” says Brooks. In linking racism to capitalism, he’s echoing Martin Luther King, Jr., who also organized in Chicago and cast his final push for justice as “The Poor People’s Campaign,” a pan-racial appeal for class-based uplift, just like the Young Lords in Lincoln Park.

This article is part of “For Whom, By Whom,” a series of articles about how creative placemaking can expand opportunities for low-income people living in disinvested communities. This series is generously underwritten by the Kresge Foundation.

Zach Mortice is a Chicago-based design writer and critic, focusing on architecture and landscape architecture. He’s written for numerous national design publications, and is the editor of Midwest Architecture Journeys, from Belt Publishing. You can reach him at zachmortice@gmail.com, or follow him on Twitter and Instagram.

_Photo_Courtesy_of_Carlos_Flores_800_536_80.jpg)

_Photo_Courtesy_of_Carlos_Flores_800_533_80.jpg)