India’s prime-time television news is known for its lively — many would say divisive — debates. One recent debate on NDTV, widely regarded as liberal media, revolved around growing public demands for a caste census to understand how educational and job opportunities are spread among India’s many caste groups. Among those who advocated for a caste-based tabulation of the population in the census was Harvard University scholar Dr. Suraj Yengde. Overlooking his academic credentials, NDTV described him as a “Dalit scholar and columnist,” leading him to tweet: “They didn’t use the prefix for me but continued using ‘Dr.’ for others.”

The privileged structures of India’s newsrooms with nationwide reach, known as national or Delhi media in common parlance, might help to explain this slip-up. Upper castes are at the top of the hierarchy of India’s millennia-old class structure that determines people’s social status at birth, and Dalits are at the bottom. The largest proportion of the population is made up of intermediate castes known as “other backward castes.” India also has a sizeable population of Adivasis (indigenous tribes). Bahujan, which translates to “the many,” is a popular term for India’s demographic majority that’s not upper caste.

Hinduism’s caste system has proliferated to religions across South Asia — and its sway over Indian media is startling. Upper castes have a monopoly over the news and knowledge circuits of India and that bias reflects in the way news is presented. A 2019 study found that upper castes, who comprise less than a third of India’s population, occupied 90% of leadership positions across national TV channels, represented 75% of anchors and two-thirds of commentators.

“Only people of a particular community are talking about everyone,” says Meena Kotwal, journalist and founding editor of The Mooknayak, a YouTube channel and online publication. Data also backs what’s visible across screens every night; panels discussing law, economy, policy, defense and the COVID-19 pandemic are overwhelmingly male. When religious minorities appear as panelists, their role is limited to talking about their religion.

Building Media Platforms of Their Own

Against all odds and away from the cacophony of the national media, diverse and marginalized socio-economic groups are seizing digital spaces to tell their stories. Their audience and influence are growing by the day among Bahujan masses. Many of the media outlets leading this movement are founded by Dalits and are leading a rich anti-caste discourse, catapulting unknown stories into the limelight, and simply providing a platform for Dalit-Bahujan creative and intellectual exchange.

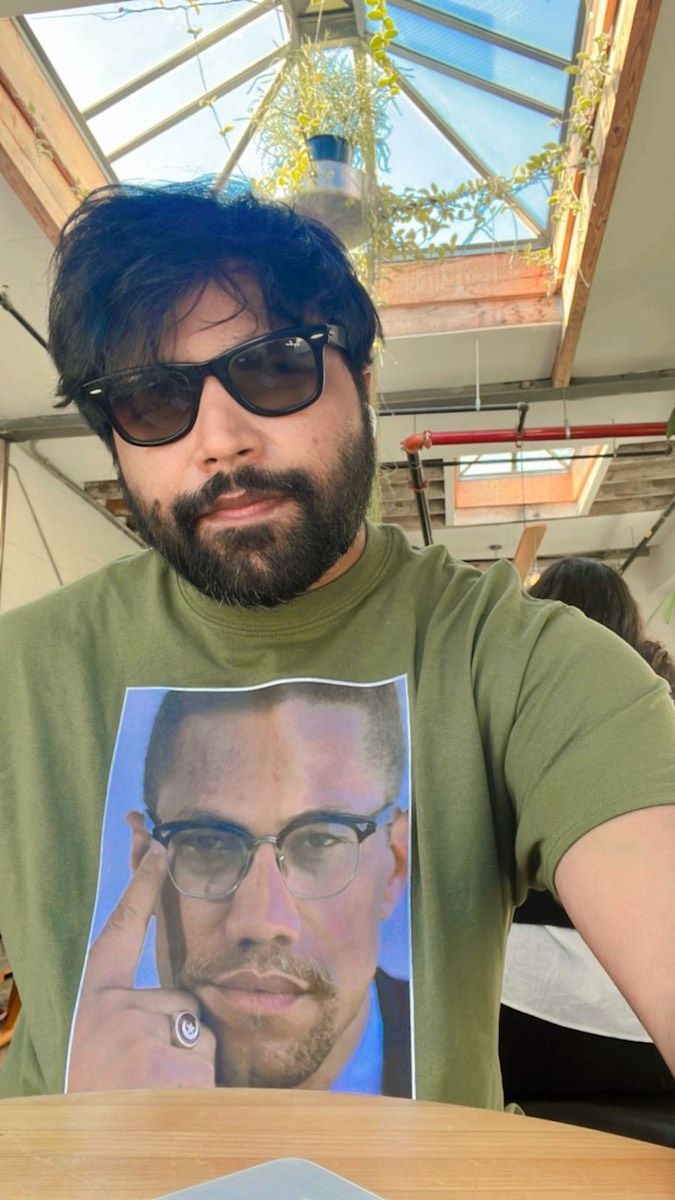

Podcaster Anurag Minus Verma (Photo courtesy of Anurag)

“When Dalits and Bahujan are talking among themselves, the experience can be informative, cathartic and very authentic in nature,” says multimedia artist Anurag, who believes the Dalit-Bahujan critique of Indian society is underexplored. His Anurag Minus Verma Podcast became one of the world’s most-listened podcasts before reaching its 50th episode. From a firsthand account of India’s prison system to microaggressions faced by Bahujan students in India’s institutions of higher education, Anurag and his guests highlight stories that are largely excluded from commercial media.

The movement is based in Dalits’ rich intellectual tradition. Kotwal’s The Mooknayak is named after one of the many publications launched by India’s civil rights icon Babasaheb Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar just over a century ago. But media jobs and prestigious assignments are still hard to come by for marginalized communities. “Every year, Dalit and Adivasi journalists graduate from journalism institutes but fail to get jobs,” Kotwal says. “One of the reasons for establishing The Mooknayak was just that.”

Sudipto Mondal agrees. Mondal is executive editor of independent digital news portal The News Minute, which reports on South India. “It will take a huge overhaul to get Dalit and Adivasi numbers in proportion to our populations in the media,” Mondal says. “The achievable thing at this point is to have senior editorial persons from our communities in leadership positions. It’s about increasing our critical presence.”

India banned caste discrimination in 1950 and officially designated Dalits and Adivasis as groups that suffered the greatest disadvantages in the traditional social order. India also runs the world’s largest affirmative action program, known as reservations, which establishes quotas for Dalits, Adivasis and other lowered castes to hold positions in Parliament, state legislatures, government jobs and government-run educational institutions. But there are no reservations in the private sector, including media. In an environment of corporate consolidation and growing inequality along caste and class lines, no one expects the private sector to champion diversity. So unsurprisingly, the advertisement-driven national media caters to the urban affluent and habitually neglects issues that affect the lives of majority of Indians.

While digital channels have opened up new spaces for Dalit-Bahujan perspectives, hate and harassment have also exploded. UN rights experts recently wrote to the Indian government, expressing concerns over death threats against Kotwal. “Digital space is the exact replica of how things work in the physical world,” Anurag says. “The same problem, whether it’s casteism, sexism or Islamophobia, has migrated online.”

Mockery of accents and clothes, jokes about affirmative action and casteist slurs are all too common, especially in elite-dominated spaces such as Instagram. In this milieu, satire is a powerful tool. Before launching his podcast, Anurag had garnered a large following on Instagram by posting short videos that subverted trending clips and memes with his distinct social commentary. “Pop culture spaces are an immense medium to influence the mind without people realizing it,” he says. “People laugh at something, but it stays in their minds.”

An Indian-American Progressive Movement Grows

India’s influential Dalit voices are well connected to a growing South Asian civil rights movement in the U.S. that has started challenging the diaspora’s historic silence on caste. There are allegations, including a 2020 lawsuit against Cisco, that caste discrimination has migrated to Silicon Valley, which has a sizeable Indian American workforce and several upper-caste Hindu CEOs. Anurag was recently on a speaking tour that took him to the University of Michigan and Harvard University, while Kotwal joined virtually from India to talk about her journey in an event organized by two U.S.-based groups: the Dalit Solidarity Forum and India Civil Watch International.

This anti-caste movement in the U.S. draws its inspiration from the Black Civil Rights movement. In turn, Black journalists and scholars such as Isabel Wilkerson and Dr. Cornel West are among those who regard Dr. Ambedkar as a great public intellectual of international significance.

On May 19, numerous progressive South Asian groups came together to co-sponsor a conversation between Dr. West and JV Pawar, a co-founder of the Indian Dalit Panthers modeled after the Black Panthers. “As much as we have Dalit Black solidarity, we embrace all of those who are rendered invisible,” Dr. West told the audience. “Just like Martin Luther King, Malcom X, Angela Davis and Toni Morrison, Ambedkar taught us that in a very human way.”

Ten days later, former Black Panthers were in a small, little-known Indian city called Nanded sharing the stage with Pawar to mark the 50th anniversary of Dalit Panthers. Mondal was there to report on this historic gathering where speakers reminded the audience of efforts by Dr. Ambedkar to build solidarity with the foremost Black intellectual of his time, W.E.B. Du Bois.

Not surprisingly, the Indian national media missed this story.

These days, the greeting “Jai Bhim” (Victory to Bhim) flows as naturally in progressive South Asian circles in the U.S. as it does throughout the informal settlements of India where Dr. Ambedkar’s life and legacy are celebrated with spontaneous fervor every year on his April 14 birthday. In a sign of growing international solidarity, April 14 is now recognized as “equality day” in Colorado; Jersey City, New Jersey; and British Columbia, Canada.

Women in Media Show the Way

India’s national media is based in and around the capital Delhi, the center of the universe for well-heeled, well-connected, big-name journalists. Outside of big cities, it’s a different story. India’s first-ever Oscar-nominated documentary this year, “Writing with Fire,” is a view into the lives and experiences of journalists at Khabar Lahariya, a Dalit women-led rural news outlet. Yashica Dutt, Columbia Journalism School alum and author of the groundbreaking book, “Coming Out as a Dalit,” recently wrote this about the film’s subjects: “(They) spent years taking workshops to learn not only how to build relationships with the police, political party representatives and sources but also how to hold space as marginalized women in male-occupied territories.”

With remarkable grit and intelligence, women and women-led organizations are at the forefront of creating alternative knowledge systems. “The hierarchy of men over women exists across caste and religion, so how can Bahujan media be any different?” asks Kotwal, explaining why she took the risk of establishing her own outlet. Mondal believes that The News Minute’s female leadership is intentionally building a diverse newsroom, encouraging a healthy contest of ideas. “There is a lot of overlap anecdotally between women, queer, Dalit and Adivasi experiences,” he says. “And that intersectionality eases out some of the conversations we are having in this newsroom.”

Rich conversations about identity, culture and politics are happening in India and across the global diaspora. But so far, big media in Delhi is still not listening.

Deepali Srivastava is a writer and editor whose articles on economic and environmental issues have appeared in Forbes Asia, MSNBC.com, and strategy-business.com. As founder and president of Script the Future, she also provides editorial services to organizations.

_920_518_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)