This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberMardi Gras had just passed and the city was returning to the quiet patterns of spring when New Orleans police discovered the body of a teenager in the backyard of an abandoned house in Central City. He was dead for at least 12 hours before police discovered him alone in the yard, wearing a school uniform stained with blood from a single gunshot to his back.

Over the next several days, details of the young man’s identity emerged:

His name was Ricky Summers. He was 16 years old. His parents were both dead. He went to a decent charter school — KIPP Central City Academy — and hoped to one day attend college. On the Saturday morning police found Summers’ body, friends were expecting him at school for a tutoring session, the city’s daily newspaper reported.

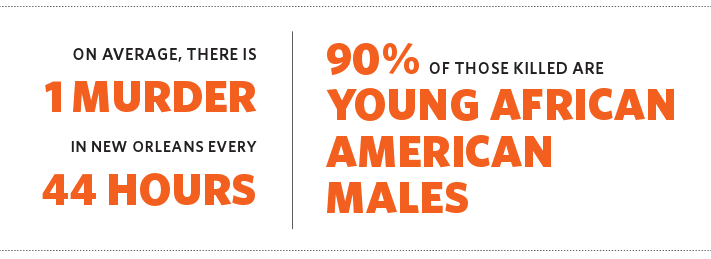

The story was distressingly familiar to many in New Orleans. The city’s murder rate has led the nation for more than three decades and almost 90 percent of the victims are young black males like Summers. More than 90 percent of the perpetrators fit the same profile.

“A lot of this is young people with no conflict resolution skills,” Police Superintendent Ronal W. Serpas told the New York Times in a recent interview.

In the week after Summers’ death, another young man not yet old enough to legally buy beer was killed by police officers. Wendell Allen, 20, was unarmed when the police shot and killed him during a drug raid in his home. Police found 4.5 ounces of marijuana, worth about $500. The shooting of Allen — a star basketball player at the public high school he attended — is now under investigation. No officers have been charged. Summer’s death also remains unresolved.

The constant gun violence has an undeniable effect on the way young people think about their future. Thariyon Bryant, 15, a student at The Net Charter High School, an alternative school in the city, recently explained that she planned to go to college, if “I’m not dead.” Bryant, a friendly girl who enjoys reading, is now on probation for assault charges. Over the last two years, she’s been in and out of the juvenile courts on four similar assault charges. Bryant’s classmate, Larron Davis, 16, explained that while he regretted getting caught carrying a gun in the French Quarter — he is now under house arrest — he didn’t regret having the gun. “It’s never safe out there,” he said. “You carry if you want to get out.” A teacher interrupted him because he was needed in the office; a group of young men were looking for him and the police wanted to escort him home, to make sure he got there safely.

Thariyon Bryant (left), 15, Larron Davis (right), 16, attend an alternative charter high school. Both have police records.

The unending violence has frustrated the city for decades. In most elections, it is a major campaign issue, if not the campaign issue. This year, Serpas began enforcing an 8pm curfew for people under the age of 16 after a bloody Halloween celebration in the French Quarter left two young men shot dead and 12 others injured by stray gunfire. The controversial curfew is now limited to the crowded, bar-dominated Quarter, but there is talk of expanding it across the entire city despite its ineffectiveness at reducing violence. The city’s last police chief, Warren Riley, infamously blamed the city’s high crime rate on “the water in the Mississippi,” hinting at some kind of natural inevitability.

An increasingly vocal chorus, however, says that the city’s violence is anything but natural. Instead, these public safety advocates argue that the dangerous streets must be examined within the context of a broken juvenile justice system that for decades has failed to properly educate, rehabilitate or integrate the city’s most vulnerable young people. If we fix the system, they say, we can fix the streets.

“The statistics show once a kid is arrested and in the court system, they have an 85 percent chance of coming back into the system for something else,” said Orleans Parish Juvenile Court Judge Mark Doherty. “Once you have that initial contact, it’s a slippery slope.”

Making change has not been easy; New Orleans is a city where ways of doing things are deeply entrenched and habits, even institutional ones, are hard to break. Yet in the past several years, Doherty and his allies have made critical gains towards accomplishing feats that many a decade before would have laughed off as impossible.

In early fall, the city expects to break ground on a $28 million, state-of-the-art juvenile justice center that reform advocates passionately fought for, and won. The 40-bed detention complex of classrooms, living spaces, offices and courtrooms will conform to the highest national standards for rehabilitative juvenile justice. The center will replace a 54-year-old dilapidated facility that was infamous for its brutal, filthy and oftentimes violent conditions.

And while the new youth facility may be the most visible sign of a changed approach to juvenile justice, other reforms in the courts, public defender system and the schools also hold huge implications. Altogether, these post-Katrina reforms carry the potential to transform the lives of New Orleans’ most vulnerable residents, and with that, radically alter the city’s juvenile justice system from a cautionary tale of failure and abuse into a national model for success.

At one point in their lives, both Darren Aldridge, 20, and Terry White, 24, expected to end up in either one of two places: Jail or an early grave. It was a reasonable expectation. They both grew up without fathers in the crime-plagued Lower 9th Ward. Many of the men in their families were in and out of prison. Others they knew dealt drugs in the neighborhood.

Aldridge has two uncles serving life terms in Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola, and a brother in Orleans Parish Prison awaiting trial. He was charged with the murder of a 15-year-old boy.

“My daddy went through the system and mostly all of my cousins, females and males,” White said.

For the two friends, however, the cycle was disrupted this year. When they caught their most recent charges — possession of an illegal firearm for Aldridge, possession with intent to distribute of crack cocaine for White — the courts, instead of tossing them into jail, gave them probation and ordered them to take classes. Both became students at NOPLAY, or New Orleans Providing Literacy to All Youth, a GED and literacy instruction program run by the non-profit Youth Empowerment Project. Each year, NOPLAY serves 700 students between the ages of 16 and 24, with the goal of graduating 50 annually. The average NOPLAY student, when first entered into the program, reads at a sixth-grade level.

“The statistics show once a kid is arrested and in the court system, they have an 85 percent chance of coming back into the system for something else. Once you have that initial contact, it’s a slippery slope.”

After more than a year attending classes, Aldridge passed the GED and graduated in May, the same day his brother went to trial for murder.

“It brought tears to my momma’s eyes,” said the New Orleans native, who has a 1-year-old son. Aldridge says he intends to stay out of trouble so he can be there for his son, unlike his own father.

“I have to switch my whole life up for him,” Aldridge said. “Everyday I wake up I see him and he motivates me.”

White recently took his GED and is waiting for the results. In the meantime, he works mentoring troubled children, teaching them the value of school and the dead-end reality of life on the streets.

“It’s easy to get caught up hanging with the wrong crowd because they’ll take care of you,” he said. “That’s how they get you in the game. I seen a dude whose daddy been dead since he was five or six and momma was on heroin her whole life. So he’s hanging out with drug dealers. They took care of him, whatever he needed. He felt right at home. That’s how it happens.”

The Youth Empowerment Project recently surveyed 108 youth enrolled in its GED program. More than 85 percent had dropped out of high school; 79 percent were unemployed; 42 percent had been arrested. But when asked how many wanted a better life, all responded “yes.”

“They want to be able to make enough money and work to make a better life for themselves and take care of their families,” Youth Empowerment Project co-founder Melissa Sawyer said. “It’s really the same thing [everyone] wants, they just don’t have the resources or opportunities.”

The process that placed White and Aldridge in GED courses is a foundation-funded initiative called the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative (JDAI). The Annie E. Casey Foundation supports about 100 JDAI sites in 24 states and the District of Columbia. It established a location in New Orleans in 2006, thanks to the advocacy of Doherty, Sawyer and their allies.

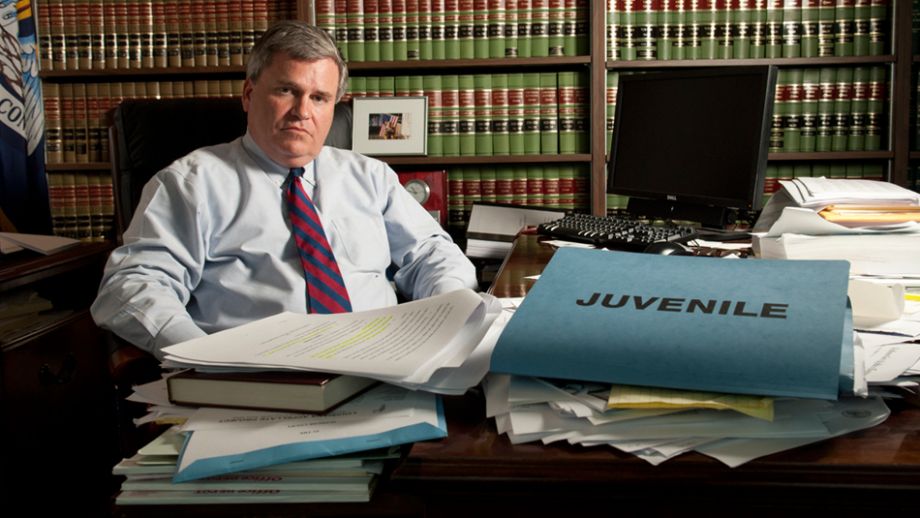

Orleans Parish Juvenile Court Judge Mark Doherty is working with other advocates to reform court treatment of juveniles.

Getting the national program to set up shop in New Orleans was one of the first tangible fruits of post-Katrina reform efforts. The goal: To reduce the use of detention for juveniles who don’t pose a public threat. To achieve this, JDAI utilizes a court-approved methodology called a Risk Assessment Instrument. The instrument works like this: When a juvenile is arrested, he or she is evaluated by the courts and, based on a set formula, given a score that determines if they are a “risk” to public safety and thus, should be detained. If their score does not indicate they pose a threat, they are free to be released to their parents. The courts can also order them into a variety of alternative detention programs that include NOPLAY, drug court, electronic monitoring and the evening reporting center, a program designed to keep children off the streets from the end of the school day until after sunset. The reporting center provides education, life skills classes, recreational activities and guest speakers.

Bart Lubow, director of the Juvenile Justice Strategy Group at the Annie E. Casey Foundation, said like all of their JDAI sites, New Orleans approached them asking for help.

“Sites have to court us and New Orleans was one of the sites actively courting us,” he said. “We don’t go to places that don’t want to do this and we don’t go to places where there is evidence they can’t do this. It’s a complicated and challenging endeavor that involves multiple partners and upsetting of the status quo.”

Lubow acknowledges that New Orleans wasn’t, at first, the most obvious candidate for the program, but that the thirst for change there ultimately convinced the foundation to invest resources.

“There was less evidence of innovation in New Orleans at the time than we might have liked to have seen within the courts and within juvenile probation,” Lubow said. “But there were enough people around the system that were not only strong advocates but creative program people that we thought this will work well.”

So far, the results of the initiative are impressive. Population at the Youth Study Center, New Orleans’ juvenile detention facility, decreased by 7.5 percent from 2010 to 2011 and admissions fell by 21.5 percent. The number of juveniles from New Orleans committed to state detention facilities fell by 33 percent. Overall, juvenile crime decreased by 68.7 percent.

Not every child, however, is eligible for the alternative detention programs and those the courts deem to be public safety or flight risks are sent to the Youth Study Center.

For years, the city-operated juvenile detention facility specialized in neglect and abuse. Children were fed spoiled milk and beans foul with maggots, earning it the nickname “Youth Starvation Center.”

Inmates did not receive constitutionally mandated education, parental visitation or medical care, according to the Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana (JJPL), a non-profit that advocates for juvenile offenders.

Staff members reportedly choked, slapped and used large iron keys to beat the boys and girls held in the aging rat- and cockroach-infested facility.

“One kid came in after he was shot and he had a colostomy bag but they wouldn’t give him his pain medication,” said Dana Kaplan, executive director of JJPL. “A kid would break his jaw in a fight and they wouldn’t treat him. It was gross neglect.”

During Hurricane Katrina, the young inmates — a number of whom had just been arrested but not adjudicated of any crime — were transferred to the city’s adult jail, where they were held for a week in a flooded facility with no electricity or running water, little food or drinking water and few guards. Many said they thought they would die there, according to a report issued by JJPL.

Dana Kaplan, executive director of the Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana, has worked since Katrina to improve conditions for juvenile offenders.

In December 2007, JJPL filed a lawsuit against the city of New Orleans, charging the city with violating the constitutional rights of young people held in the detention center. After two years of legal sparring, the non-profit won a federal consent decree requiring improvements in confinement conditions. It was a landmark moment that signaled a new way of looking at youth incarceration. The days of operating the Youth Study Center as a prison and treating juvenile offenders like adults were over, advocates said.

“There was a feeling post-Katrina where everyone was oriented towards reform,” Kaplan said. “The old ways of doing things weren’t working.”

As a result of the decree, the city hired more qualified staff, added social workers and improved educational and health services. By all accounts, violence has greatly decreased inside the Youth Study Center.

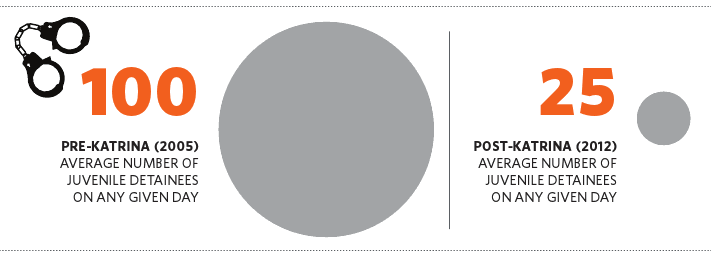

Before the storm the facility had 80 beds and typically held 100 children. The population is now down to 25, thanks in large part to the Annie E. Casey Foundation-supported Juvenile Detention Alternative Initiative.

The city also agreed to build a new 40-bed state-of-the-art juvenile facility to replace the current building. It will house the juvenile court as well as offices for the district attorney, public defenders and an array of social services, with a focus on rehabilitation as opposed to incarceration.

“I feel at this point what’s exciting is that people are working towards a common goal,” Kaplan said.

“Staff members reportedly choked, slapped and used large iron keys to beat the boys and girls held in the aging rat- and cockroach-infested facility.”

Mike McMillen, a New Jersey-based architect, has written a book on architecture of such facilities, Residential Environments for the Juvenile Justice System, and designed numerous facilities across the country. He worked as a consultant on the Youth Study Center design and left New Orleans impressed. “They are not skimping on programs and services and saying we can get by with a little,” he said. “It’s just loaded with all of the best possible stuff.”

The consent decree and construction of the new facility are emblematic of greater coordination between every stakeholder in the juvenile justice system, Kaplan said.

“There is a greater orientation around not just locking up as many kids as possible but targeting taxpayer dollars effectively at programs that work,” Kaplan said. “The facility itself is being redesigned to focus on therapeutic programming and actually having mental health and educational services. This correlates with the comprehensive reforms we’re seeing of the juvenile justice system as a whole.”

Sarah Bryer, director of the National Juvenile Justice Network, said the redesigned Youth Study Center — and the acknowledgement among New Orleans officials that the emphasis should be on rehabilitation, not youth incarceration — is part of a larger national trend.

States such as California, New York, Texas, Ohio and Illinois are providing financial incentives to local communities to keep their juvenile detention population numbers as low as possible. Studies show that incarceration is expensive, harmful and actually increases youth recidivism, Bryer said.

“Budget crises are giving governors and legislators a chance to rethink and retool their strategies,” Bryer said. “Many are realizing that incarcerating youth is something where they are not getting any return on their investment because the kids are coming out worse.”

Even so, state budget cuts have put at risk the few programs that are available. The Louisiana Office of Juvenile Justice, which operates four secure-care detention facilities in Louisiana, announced in March that it wanted to eliminate its $4.3 million contract with the Florida-based non-profit AMIkids, a state-funded day treatment program that provides educational services for more than 900 troubled youth.

Mary Livers, deputy secretary of the office, told the Legislature she didn’t see a need for the program anymore since the juvenile crime rate is decreasing.

Before Katrina, four part-time public defenders handled all indigent juvenile offenders. The lawyers worked out of their own offices and had no shared support staff. A 1997 New York Times article described them as inexperienced, ill-prepared, ill-equipped and out of touch with their clients. “It’s medieval,’‘ Anne Turissini, who spent five years as a juvenile defender, told the Times. She earned $18,000 a year to handle hundreds of cases. “You are supposed to go along and get along with your judge, she said. “And if you object too often in court, they will have you fired.”

After Katrina, former staff members with the Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana seized the opportunity to reform the public defender system. They created something called Juvenile Regional Services (JRS). It was the first standalone juvenile public defender office in the country.

JRS represents a sea change. There is an executive director, five full-time attorneys, two investigators and two youth advocates.

Patricia Puritz, executive director of the National Juvenile Defender Center, said JRS is a model the rest of the country should follow since many cities and states continue to operate without an independent agency dedicated exclusively to juvenile defense.

“The intention of JRS is to have a public defender office that specializes in juvenile defense, that can attract people who want to be there, who won’t be rotated out into adult court and who can create and provide comprehensive legal services,” Puritz said. “Having [Louisiana] recognize JRS as playing a vital and important role and needing to be independent to do that is another step in what we hope is a culture change around juvenile defense.”

JRS, however, is troubled by a lack of resources.

Last year, the five attorneys handled more than 1,000 cases, including over 500 new ones. Unlike the adult public defender system, they are required to perform more than just court representation.

A public defender’s responsibility to an adult client ends after a sentence is imposed. In juvenile court, however, public defenders are responsible for their clients for as long as they are under the supervision of the court. If a youth is sentenced to five years in secure custody or five years of probation, the public defender remains responsible for the needs of that child, ensuring they receive adequate medical care, education and ongoing legal counsel, until he or she is released.

Josh Perry, executive director of Juvenile Regional Services, said this is a vital part of their job.

“It means our clients can rely on us, that we don’t throw them away just because they don’t have a guilt or innocence issue,” he said.

Due to limited resources, however, it is impossible for the five JRS attorneys, who typically handle up to 150 cases at any one time, to fulfill this obligation for all of the people they represent.

“It’s incredibly hard and very time consuming and I would never pretend that we do everything we want to do on every case. We couldn’t possibly,” Perry said. “Too often we’re forced to triage our time and it’s very difficult for us and not fair for our clients.”

The budget of JRS for the upcoming fiscal year is $928,000, but only $510,000 of that comes from direct state funding, forcing Perry to raise the rest through grants and donations.

If they settled for just what the state provided, JRS would be limited to court representation and would not be able to provide any follow-up assistance such as education advocacy and social services, Perry said.

“Those things authentically are the responsibilities of the state, and outsourcing it to foundations is not a sustainable recipe for reducing juvenile recidivism and improving graduation rates that will make a difference in terms of the safety of our city and the prosperity of our youth,” Perry said. “I am proud and happy to take on that fundraising responsibility right now but I don’t think people can get in the habit of thinking this is a way to sustain a juvenile justice system.”

The budget struggles at JRS are not unique, Puritz said. Juvenile public defense across the country is “under-funded, undervalued and misunderstood so it’s never even had a chance to fully do its job,” she said. “Society at large doesn’t appreciate or value the important role of the public defender and most especially the juvenile public defender. But it’s remarkable how quickly people’s attitudes change when it’s a child they love or know who needs help. Suddenly they see public defense in a completely different way.”

Ernest Johnson becomes animated when he talks about society’s failure to protect its children, but grows quiet when it comes to his son.

“I can’t go into details,” he said. “It’s a high-profile case.”

Johnson, 55, struggled with heroin addiction most of his life and spent 30 years in and out of prison for various crimes.

He warned his son, Ernest Cloud, not to follow in his footsteps. He didn’t listen.

Cloud is one of three people charged in the 2009 shooting death of Wendy Byrne, a popular French Quarter bartender who was killed walking on a quiet side street in the touristy neighborhood. The murder of the 39-year-old white woman received significant media coverage. As the father of one of the alleged killers, Johnson felt isolated so he reached out to the Families and Friends of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children, a New Orleans-based prison reform advocacy group. The non-profit helped him navigate the oftentimes-baffling criminal justice system. Eventually, he became the group’s community organizer.

Cloud, who was 14 years old at the time of the murder, is currently in jail awaiting trial. The other two suspects, Reggie Douglas and Drey Lewis, were 15. Johnson continues to go to meetings and speak out on behalf of the rights to fair treatment, and ultimately a future.

“It’s remarkable how quickly people’s attitudes change when it’s a child they love or know who needs help. Suddenly they see public defense in a completely different way.”

At a recent panel discussion on juvenile justice in New Orleans, the moderator asked four experts how they would grade, on a scale of 1 to 10, efforts to reform the city’s juvenile justice system.

The average score given was a six.

Ernest Johnson's son was 14 years old when arrested on a charge of murder. The experience inspired Johnson to begin counseling other families ensnared in the justice system.

“We incarcerate more youth than any other country,” said Sarah Bryer, director of the National Juvenile Justice Network. “We have gotten off track and getting us back on track will take time and effort, but New Orleans is doing great and I have to give credit to the advocacy community. Sometimes bureaucracies will keep moving along the same path they’ve been moving for the past decades. It takes the power of advocates to partner with administrators, courts and foundations to push for change.”

The discussion, organized by The Lens, a local public interest news organization, was held at a cultural center just a few blocks from where police discovered the body of Ricky Summers, the 16-year-old boy shot to death behind an abandoned home in Central City. [Disclosure: The Lens and Next American City are content partners. – Ed.]

Today, the spot of land where Summers fell and drew his last breath betrays no evidence of his death. The weeds and vines continue to grow wild, nearly overtaking the entire block of gutted, boarded-up shotgun houses.

There are thousands of places like that throughout New Orleans, the forgotten final resting grounds where young men and women fell in a hail of bullets and died in pools of blood; sidewalks, porches, neutral grounds, basketball courts, parks and the middle of heavily-trafficked streets. Two months after the murder of Summers, police arrested 18-year-old Kendal Marcelin in connection with the killing of a 15-year-old boy. Like Summers, the boy’s body was discovered in a grassy lot next to an apartment complex. He had been shot in the face.

Two days later, Brandon Adams, 15, was shot to death while walking home following a pickup basketball game. His brother, Erik Adams, 17, was shot in the back and leg but survived. Brandon’s family described him as a role model and a helpful, happy-go-lucky A student, according to the daily paper. Three days after that, the body of 15-year-old Christine Marcelin, the younger Adams’ girlfriend, was found in a secluded section of eastern New Orleans. She had also been shot.

Their killers have not been found.

This is why, despite the significant changes that have taken place since the storm, it is irresponsible to declare victory, said Judge Ernestine Gray with Orleans Parish Juvenile Court.

“Maybe ‘Joe Blow’ citizen hasn’t said to the mayor, ‘Enough. This is important and we want you to address it,’” Gray said. “Maybe we’re all to blame that we haven’t come together and said in a unified voice, ‘Yes, we believe our children are our greatest natural resource and we are going to make decisions that support that belief.’”

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Richard Webster is a staff writer for New Orleans CityBusiness, where he has worked since 2004 covering crime, health care, tourism and social justice issues. He has won local, state and national awards for his coverage of the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and the ongoing recovery. He previously worked at Tico Times in San Jose, Costa Rica.

Andrew Cook is a photographer and writer. His work moves between fine art and editorial, focusing consistently on issues of contemporary urban life. He has published two books of photographs and contributes regularly to Next American City. Cook will be enrolled at MIT in the fall as a candidate for a Masters of Community Planning. Until then, he will be making sandwiches in the woods of Vermont.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine