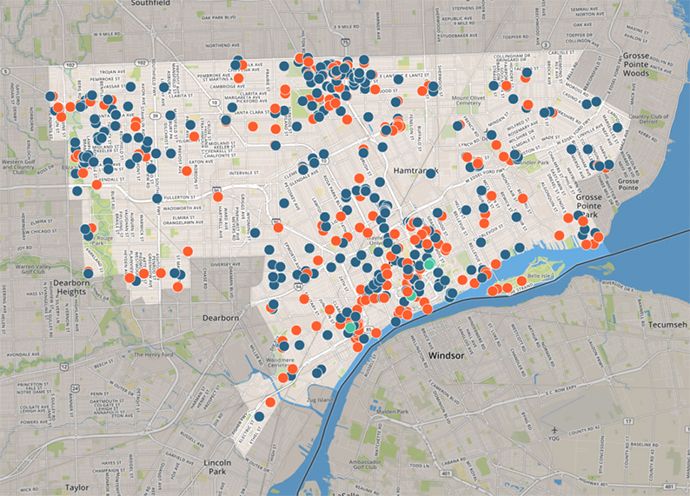

To get a sense of how Detroiters think about sustainability in their city, you can start with this map. Location-based comments left by residents point out what they like — native plants sprouted in empty lots, proximity to transit and access to parks — and what they don’t, which ranges from lack of bike lanes to vacant properties.

Residents can support comments left by other residents, and occasionally, the City of Detroit chimes in after suggestions. “Great comment, Dave. This will help inform the planning for greater mobility,” the city responds to a suggestion of rehabbing a downtown bus station.

It looks a lot different than the typical community meeting, though this digital map is not necessarily meant to replace it. The map is one of many efforts Detroit’s Office of Sustainability has taken to ensure robust community input for its Sustainability Action Agenda, due to come out next spring.

The office is less than two years old and runs on a staff of three, says Office of Sustainability Director Joel Howrani Heeres. Though matters of sustainability were not ignored by residents or city agencies, he says, “they have not been focused on in a unified way.”

The office set two early goals: first, making government operations more efficient by reducing energy costs. Second, utilizing that money to address resident-focused solutions to the city’s sustainability needs.

Heeres wants to address the immediate needs of Detroiters before aiming for big-picture sustainability goals set in other cities. Over 130 cities across the U.S. have some kind of sustainability plan; many aim to be carbon neutral in 30 years.

“We have myriad challenges that are different than a lot of other cities that have been the vanguard of sustainability,” Heeres says.

The office decided on a holistic approach engaging residents on everything from housing to green space to energy bills to waste and air quality. It set a goal to engage with at least 7,000 Detroiters, a number surpassed in this year’s online and offline process.

This “intensive engagement,” as Heeres call it, included a survey (available on paper and online), meetings with local organizations and four town halls. Fourteen sustainability ambassadors, two per council district, focused on specific neighborhoods, where they attended community meetings, passed out surveys and spoke with residents.

The digital map — and the invitation to leave feedback on it — is the result of a partnership with coUrbanize, a tech startup founded out of MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning. Co-founder Karin Brandt, previously a city planner, got the idea after realizing many community engagement processes weren’t attracting diverse audiences, but rather only attracted residents more likely opposed to change.

“In terms of community engagement,” Brandt says, “Tech is a really important solution to supplement the existing process, but I don’t think it replaces it.”

Heeres points out Detroit is still a city with a significant “digital divide” — a 2017 report found that approximately 40 percent of Detroit households remain completely offline. He says that responses to the office’s paper surveys were more representative of city demographics than the responses online.

Still, the team found ways the digital and in-person engagement could complement one another. coUrbanize requires everyone who participates to use their real name, much like you’re asked to sign in at a community meeting. But it doesn’t collect additional data around race or income level.

“The analytics showed we actually had some gaps in key districts where there wasn’t as many responses coming from the online platform,” says Katrina Lewis, a senior consultant with AECOM who helped coordinate engagement with the Office of Sustainability.

The team posted yard signs in those areas with a phone number for residents to text their feedback. Results were mixed, says Lewis. They also increased boots on the ground with more location-specific outreach by sustainability ambassadors.

Late this summer, the team added a new phase of engagement after residents asked for more research material from the office before it finalized an action plan. The Office of Sustainability held focus groups in October and November with Arabic and Spanish-speaking communities, faith-based communities and youth.

Lewis found the digital supplement helped as a way to maintain conversations around sustainability after community meetings. “It was a way to remain present in people’s minds, either by posting updates or leaving general questions open on the site,” she says. “There’s not a cost-effective way to do that otherwise.”

With the community process wrapped up, the Office of Sustainability will spend the next few months sorting through feedback to set its sustainability agenda. It expects to release Detroit’s Sustainability Action Plan in April.

“We haven’t gotten to this point yet,” Lewis says, “But those map comments will help us think through where solutions might make sense to pilot or put in place.”

Emily Nonko is a social justice and solutions-oriented reporter based in Brooklyn, New York. She covers a range of topics for Next City, including arts and culture, housing, movement building and transit.

Follow Emily .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)