In the summer of 2017, violent, white supremacist marches in Charlottesville, Virginia, made headlines and left three dead. In the aftermath, residents looked for ways to heal and make change, and the Charlottesville Area Community Foundation created the Heal Charlottesville Fund. In 2018, that fund awarded nearly one million dollars to organizations and initiatives aimed at addressing systemic racism. Mapping C’Ville received one of those grants to map out the restrictive racial covenants that for decades restricted where African-Americans could purchase property. Jordy Yager, the project’s creator, says Mapping C’Ville aims to uncover the roots of the city’s stark racial disparities with the hope of prompting policy solutions.

Mapping C’Ville is one of several mapping projects that are examining the impact of racist policies on urban spaces. Yager says he was inspired by the Mapping Prejudice in Minneapolis and Mapping Segregation: DC projects, but researchers have also explored the impact that redlining and segregation have had on Seattle and other cities. The Seattle project prompted a 2006 state law that helps neighborhood homeowners’ associations eliminate (now unenforceable) racial restrictions from outdated bylaws.

Yager is a journalist and a Charlottesville native who undertook the mapping project as an outgrowth of his work on housing and racial equity in the city. He is working in partnership with the Jefferson School African-American Heritage Center. Yager points to the Opportunity Atlas study conducted by Harvard economist Raj Chetty, which maps people’s social mobility to the environments they grew up in. The Opportunity Atlas ranked Charlottesville low on the list in terms of people’s ability to move out of poverty over their lifetimes.

This, Yager says, points to a structural problem.

“[Charlottesville] does not think of itself that way. It’s very liberal. It’s a university city. It’s a blue dot in a purplish county,” Yager says. “I started looking at census tracts,” Yager says, examining incarceration rates, median income, and education levels on the map. A quarter of Charlottesville residents live in poverty, for example. What he saw was “that your environment, where you live, is the number one predictor of what happens to you in life.”

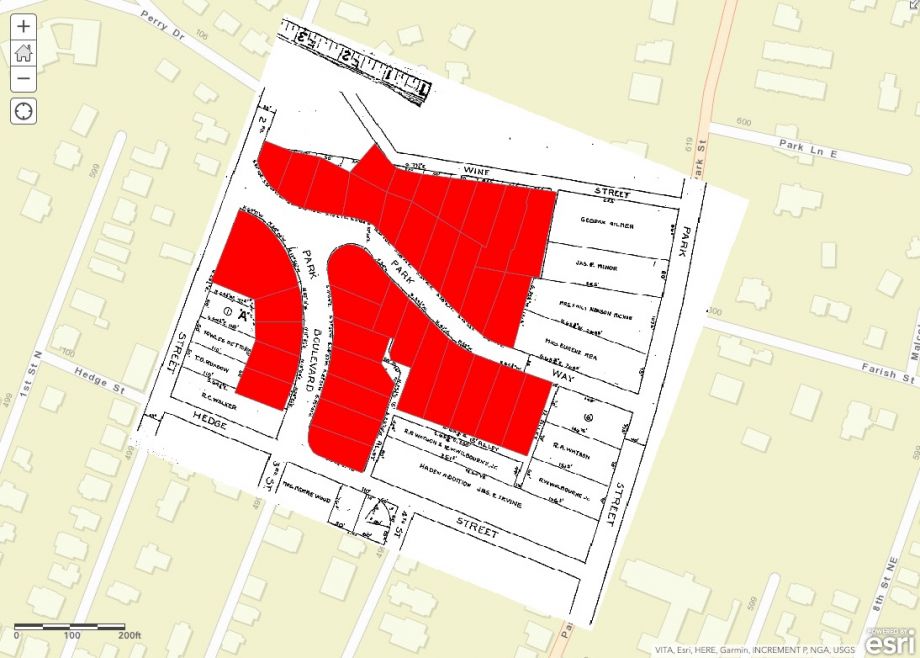

“If where we live determines what happens to you in life, why do we live where we live?” Yager asks. Asking this question led him to start examining property records. He requested records from the city and county and received more than 300,000 digitized property records. Although they were digitized, the records weren’t searchable, which meant they had to be examined individually. That examination, while still ongoing, has already revealed the frequency of racially restrictive covenants.

Andrea Douglas, executive director of the Jefferson School African-American Heritage Center in Charlottesville, says that property ownership is one of the key determinants of the conditions for African-American people in the city. The records project reveals the way policies cut into African-Americans’ possibilities for economic advancement.

“What we’re doing with this mapping project, is describing that notion in its fine-grained detail,” Douglas says. “At the same time, suggesting … the kinds of nuances even of the word property. People who were once owned then become agents and have ownership, and what are the deterrents or what is created so that that agency is taken away? That, essentially, is what Jim Crow is,” Douglas says.

Douglas points to zoning laws and property restrictions as tools used to preventing prosperity. Many of these laws, Douglas notes, arose in the early 1920s, when the Ku Klux Klan was powerful and the 19th Amendment threatened to swell the voting rolls with newly enfranchised African-American women.

Property issues, however, also relate to health and educational outcomes, Douglas says. One example she offers comes from the records of a 1930s debate over laying a sewer line that would serve a white high school. While the sewer line was laid, the adjacent African-American neighborhood, Pearl Street, was razed in the process.

Decisions about where and when to place critical infrastructure have implications for both physical and economic health, Douglas says. “Doing a covenant map such as this, and laying on top of it the utilities,” Douglas says, “When you lay on you can also get a public health story.” As a result, mapping the property records and racial covenants, and superimposing infrastructure records, produces “a layered narrative,” Douglas says. She recalls a visit to the public health office where she and Yager reviewed public-health maps and mortality rates.

The records showed disparities across neighborhoods, and Yager and Douglas were able to see the impact that building sanitation infrastructure had. While the white high school and community got access to sewer and water lines, the African-American community was left without. Open-air disposal of sewage leads to greater likelihood of disease. She emphasizes that although Charlottesville industrialized early, parts of the city were left without this basic sanitation infrastructure until well into the 20th century. “We think about infrastructure in one way, but we don’t think about the implications of not having infrastructure,” Douglas says. “[People] take a lot of [infrastructure] for granted because they’ve never not had it.” The Mapping Charlottesville project is developing a proof-of-concept proposal for a set of maps that will look at infrastructure that had to get city council approval, such as sewer and water lines and paving roads. This will be superimposed on the racial covenant map, and Yager plans to add a third layer that will look at how home values changed, which would show the relationship between the covenants, infrastructure and wealth building.

Ten years ago, Robert Nelson, director of the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of Richmond, embarked on the Mapping Inequality Project to identify how the Homeowners Loan Corporation (HOLC), a federal agency created under the New Deal, redlined certain neighborhoods in cities. The project, Nelson says: “helps advance conversations about inequities and particularly, the federal government’s role in creating those inequities in American cities in the 21st century.” The data he used didn’t include Charlottesville, he says, because at the time HOLC was operating Charlottesville didn’t have a large enough population to qualify for its services. Still, Nelson is happy to see the Charlottesville initiative, and, he says, the work is having an impact since redlining is now a topic that Democratic presidential candidates are addressing in their debates.

There are more than 100 volunteers helping review the documents and enter them into a searchable database (and others can help online), Yager says. He hopes that uncovering the way racial disparities were embedded in the city’s development will prompt residents and policy makers to reflect on and come up with ways to tackle those disparities head on.

“This is very much a personal history for [the volunteers] as well,” he says, explaining the motivation for people to get involved in the project. Charlottesville residents, he says, want to help and want to be engaged, but often there is an action step that is missing that impedes people from moving from desire to action. Yager sees the Mapping C’Ville project as a way for well-intentioned residents to get involved in uncovering the past and setting the stage for change. “These are our neighborhoods; this is our history. Let’s be a part of unpacking this and connecting the dots,” Yager says.

This article is part of “For Whom, By Whom,” a series of articles about how creative placemaking can expand opportunities for low-income people living in disinvested communities. This series is generously underwritten by the Kresge Foundation.

Editor’s note: We’ve corrected the name of one of the streets that was razed in the 1930s to lay a new sewer line. We’ve also corrected the name of the Heal Charlottesville Fund.

Zoe Sullivan is a multimedia journalist and visual artist with experience on the U.S. Gulf Coast, Argentina, Brazil, and Kenya. Her radio work has appeared on outlets such as BBC, Marketplace, Radio France International, Free Speech Radio News and DW. Her writing has appeared on outlets such as The Guardian, Al Jazeera America and The Crisis.

Follow Zoe .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)