EDITOR’S NOTE: “Hear Us” is a column series that features experts of color and their insights on issues related to the economy and racial justice. We acknowledge that the series title does not honor the experience of Deaf people, so we’re revisiting the column’s name so as to not uphold audism. Follow the series here and at #HearUs4Justice.

WRITER’S NOTE: Throughout this op-ed, I use the terms “disabled people” and “people with disabilities” interchangeably. The use of identity-first language honors the linguistic shift that self-advocates within the disability community have ushered in over the past years, while affirming that our community is not a monolith and each of us has a right to self-identify as we so choose.

Today’s COVID crisis leaves no doubt that U.S. policymakers continue to view disabled people as disposable. The unfathomable loss of life over the last two and a half years is the outcome of policy choices rooted in organized abandonment and eugenics.

The COVID crisis is a mass disabling event, and it’s a stark reminder of the profound consequences when policymakers ignore ableism’s central role in maintaining economic and racial oppression. Advocates of Disability Justice (DJ) — a framework created by disabled queer activists of color — have long sounded the alarm on the harms of ableism, an entrenched system that targets disabled people, persecuting and punishing them because their bodies and minds don’t uphold socially constructed norms. DJ represents a point of departure from the solely rights-based and single-issue focuses of the past, advancing instead an intersectional and collective vision for liberation and justice.

As too many people still yearn to return to “normal” — a time marked by deep inequities made worse by COVID, and in which our economy and society only worked for the powerful, non-disabled, wealthy and white few — it is crucial that we confront ableism in ways that center those most harmed by its reach. This is an especially important consideration for those of us working to break free from the shackles of white supremacy and capitalism.

July 26, is National Disability Independence Day, honoring the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), signed into law in 1990. As societal pressures and state interests have redefined the legal bounds of disability over time, the primary issue that policymakers, organizers, and advocates must contend with remains the same: who wields power and who is rendered powerless by systems and policies in place.

Thirty-two years after the ADA’s passage, Black disabled women remain disproportionately burdened by the preservation and justification of ableist oppression.

The Entanglement of Disability, Race, and Gender

The legal classification of disability in the US has always been tied to one’s ability to produce labor, which is itself heavily racialized and gendered. This, of course, goes all the way back to the legitimization of chattel slavery. From the antebellum period to today, tools of social control, including pathologization and medicalization, have been wielded to structurally marginalize certain groups in service of the economic and political interests of the predominantly white, wealthy few in power. The resulting matrix of mass institutionalization, eugenics, and criminalization continues to marginalize disabled Black women today, causing toxic stress and premature death.

As noted above, our government’s eugenic response to COVID has accelerated the rising prevalence of disability in the U.S. In 2021, 1.2 million more people identified as having a disability compared to 2020. Much like race, the incidence of disability is more heavily concentrated in certain geographic areas and within specific communities. Consistently, Black people as a whole have rates of disability up to 2.5 times greater than white people.

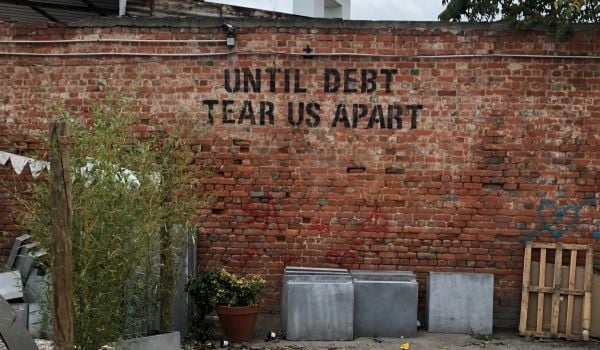

Additionally, only 27% of working-age Black disabled women had a job in 2020, which is especially alarming when juxtaposed to white women with disabilities and white disabled men at 33.7 percent and 40.3 percent, respectively. In the same year, 25% of Black adults with disabilities lived in poverty, compared to 14% of white disabled adults. Disabled people as a whole are shut out of the paid labor economy at extraordinarily high rates, with Black disabled women especially affected. And because the state rations access to healthcare and other life-sustaining resources by employment status, the consequences of such economic disenfranchisement are life-altering. Even when Black disabled workers are able to access the labor market, they are met with pay inequity (among other injustices), receiving only 68 cents for every dollar earned by white workers with no disability.

Ableist oppression reaches far past the workplace. Prisoners at the state and federal levels are about 2.5 times as likely as the general adult population to report having a disability or chronic illness. In this domain too, Black women are especially harmed as they are more likely to be incarcerated than their white counterparts. People with mental health disabilities, Black women in particular, face constant risk of involuntary institutionalization, showing one way that carcerality and surveillance extend beyond the walls of prisons and jails.

Together, these policy arrangements cast Black disabled people and their lives as expendable. Similar to the Black Women Best (BWB) framework, Disability Justice (DJ) serves as a point of departure from single-issue advocacy. Jointly applied, these frameworks have the potential to disrupt the drivers and consequences of ableist systems, including economic domination and exploitation. It should be noted that DJ centers the liberatory possibilities of community organizing and grassroots movement-building, but its 10 core principles offer a pathway toward transformative policymaking too.

Disability Justice and Black Women Best

Disabled people, Black women in particular, deserve to thrive. The DJ framework acknowledges the innate value of human life and, in line with BWB, “holds a vision born out of collective struggle,” as stated by Patty Berne and elevated by Sins Invalid. As Berne’s working draft on Disability Justice further explains, central to DJ is the understanding that:

-

“All bodies are unique and essential.

-

All bodies have strengths and needs that must be met.

-

We are powerful, not despite the complexities of our bodies, but because of them.

-

All bodies are confined by ability, race, gender, sexuality, class, nation-state, religion, and more, and we cannot separate them.”

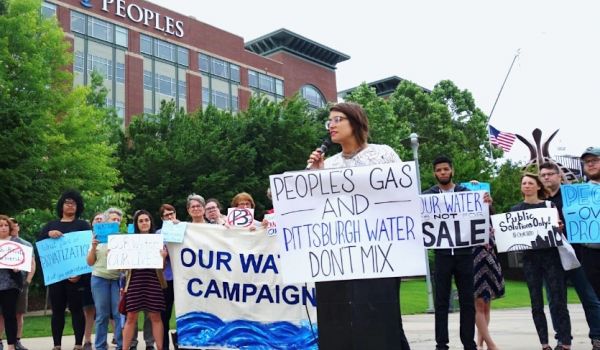

At minimum, DJ and BWB policymaking must unconditionally provide access to the life-giving resources and community-rooted care that we all need and deserve. By centering Black women, we are better positioned to craft policies capable of facilitating such transformative change for all marginalized groups. Additionally, complementary policy measures must be taken, including those that divest from criminalization and surveillance; disrupt and reverse the capture of public goods by private interests; and meaningfully include and center Black disabled women in the ideation, design, and implementation of DJ and BWB policy.

Abolitionist geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore reflects that “where life is precious, life is precious.” To dismantle all policies that are, by design, incompatible with all life, BWB must be jointly applied with DJ. When Black disabled women’s lives and their needs are viewed as precious — and protected as such — then everyone’s lives and needs will no longer be controlled by the oppressive people and systems that deny us the collective space to not just live, but thrive.

Azza Altiraifi is the senior policy manager at Liberation in a Generation.