One Oakland, California, resident wanted the faded crosswalks at the corner of 57th Street and Martin Luther King Jr. Way repainted. Another suggested the city put up signs documenting Oakland’s history, including the birth of the Black Panthers. Someone requested a database about housing discrimination. Others asked for job training. Others still requested homeless shelters or mobile bathrooms for the homeless, senior centers, childcare centers for working mothers, or streetlight repairs.

After weeks of generating such ideas, 1,200 Oakland residents in two city council districts voted for their top priorities in the first-ever participatory budgeting process applied to federal community development block grant (CDBG) money.

“I wanted to try to empower residents, particularly residents who have not been involved in the budgeting process and get them engaged,” says Oakland District 2 Council Member Abel Guillen.

President Donald Trump wants to eliminate CDBGs, but a House budget has proposed keeping the funding, at an amount of $3 billion. Getting more people involved in allocating CDBGs may help solve a built-in weakness: lack of awareness about the help to cities that the funding source provides, with everything from small business support and job training to keeping drinking water safe.

Oakland’s CDBG participatory budgeting process was a pilot, and involved deciding how to spend $784,678 over two years to benefit low- and moderate-income residents in Oakland Council Districts 1 and 2. The city has had a community participation plan in place since 1978, which governs how the city allocates CDBG dollars and other federal funding streams. Each district has a resident board that helps set the priorities. Participatory budgeting expanded on that.

“We had community meetings, meeting residents where they’re at, churches, community centers, neighborhoods and schools,” says Guillen, whose district is the most diverse in Oakland, ethnically, racially and economically. “It was pretty extensive outreach that we don’t typically do in the regular process.”

The Participatory Budgeting Project (PBP) helped. The process required five languages — English, Spanish, Mandarin, Cantonese and Vietnamese — and PBP partnered with Oakland’s Asian Pacific Environmental Network throughout all phases, including the search for interpreters.

“It was a learning process for us about the importance of not just getting things translated but also getting translations reviewed to make sure things are accessible and also make sense for what we’re doing,” says Ginny Browne, PBP project manager in Oakland.

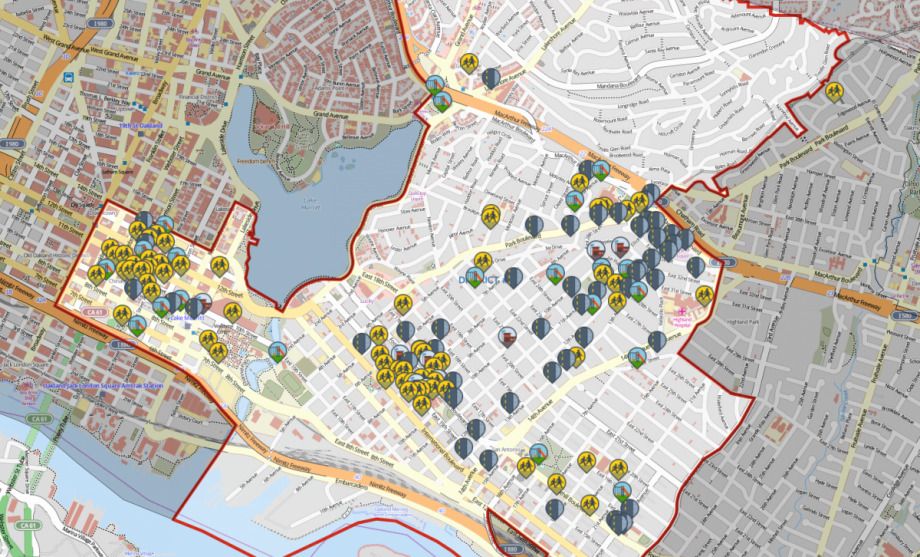

A map of Oakland City Council District 2, with markers showing where residents pointed out needs (Credit: Participatory Budgeting Project)

PBP used the same interpreters throughout the whole process, from translating printed materials to conducting budget assemblies, the gatherings where residents proposed ideas. Guillen says about 700 of his district’s residents participated in the assemblies and other forums.

“It’s really unheard of in previous processes we’ve had, really talking to residents in their own language,” Guillen adds.

The biggest challenge was the timeline. PBP started working with Oakland’s existing CDBG District Boards to serve as a steering committee back in November. The committee set rules for the process, including voting age. In this case, there was no voting age minimum.

“That was really exciting,” says Roselyn Berry, community engagement coordinator at PBP. “We were able to do voting at elementary schools. Contrary to popular belief, young people were excited to vote on things.”

An online platform launched in December, followed by budget assemblies in January, and voting in February. By contrast, with New York City participatory budgeting, there are typically several months of budget assemblies, followed by several months of transforming ideas into project proposals, then a few weeks of campaigning before voting begins. The federal CDBG timeline dictated that Oakland work much more quickly.

“I would have liked to have taken a little bit more time to get more outreach,” Guillen says. “We hope to build on this experience for the next time around. If there’s still a CDBG program in the future.”

With the votes in, the winning priorities in each district were compiled into a document meant to guide the district CDBG board and city council in shaping requests for proposals (RFPs) for CDBG dollars. Those RFPs, Guillen says, have just started to go out.

“This is also the first time that funds in a participatory budgeting process were explicitly intended for low- to moderate-income communities,” Browne adds.

Guillen hopes to expand participatory budgeting to the community benefits agreements that are emerging, tied to the influx of development in Oakland. “Rather than coming from City Hall and taking a top-down city approach, we want to listen to residents and get their feedback as to how those dollars are to be used,” he says.

It’s not the first time Guillen has sought to expand Oakland communities’ control over finances. Previously, as a trustee of Peralta Community Colleges, Guillen spearheaded the effort to move the community college networks’ bank accounts out of big banks and into local community banks and credit unions. That was back in the aftermath of the subprime mortgage crisis. He says he was inspired previously by the anti-apartheid divest movement, which has some of its roots in Oakland.

“We know the power of the purse,” he says.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)