It’s been three years since President Obama moved to protect qualifying young foreign-born people from deportation with the introduction of the Deferred Action of Childhood Arrivals (DACA). The way DACA — which allows some undocumented immigrants who entered the U.S. when they were younger than 16 — has played out in urban United States is highly reliant on the actions of local governments and advocates, according to a new report.

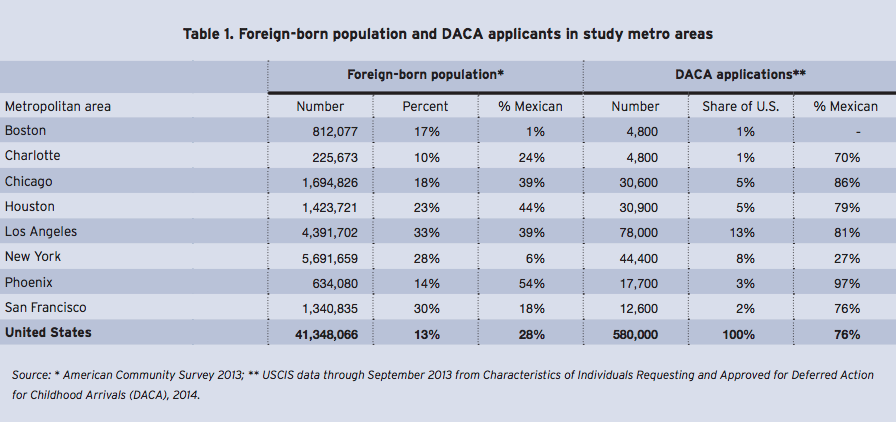

Brookings’ “Local Insights From DACA” looked at the implementation of the program in eight metropolitan areas that together account for almost half of the foreign-born population in the country (47 percent).

Though Los Angeles and New York are the most populous cities when it comes to immigrants, Brookings also looked at Boston, Charlotte, Chicago, Houston, Phoenix and San Francisco to explore the common challenges and unique struggles for immigrants in those places.

Drawing on interviews with immigrant services providers, advocates and local governments to better assess the implementation of DACA, Brookings notes that overall, local governments have stepped up to educate their residents about the ins and outs of the process, and tackled perceived barriers to application.

Although DACA is a federal program, it requires civil society intermediaries and state and local governments for implementation. Nothing in the executive action gave an explicit role or funding to intermediaries, but they ramped up services quickly. In the initial months of the program, hundreds of thousands of people applied, and civic and immigrant support organizations, state and local governments, and foreign governments responded to requests for information and assistance, documentation to prove identity and continuous residence in the U.S., and legal advice.

The varying contexts in this study’s eight metro areas affect the funding and services that support the DACA-eligible population and ultimately influence immigrants’ decisions about applying. In places with a longer history of receiving immigrants, individuals may decide that the cost and risk of applying are not worth it if they are already able to work and live without constant fear of deportation. In locations with stricter enforcement mechanisms, the eligible population has a greater motivation to apply.

In the last several years, of course, cities across the U.S. with large immigrant populations have taken their own steps to protect their foreign-born residents. In Philadelphia, Mayor Michael Nutter signed an executive order in 2014 that essentially ended the city’s cooperation with the federal law enforcement focused on deportation. New York City last year approved the largest municipal ID program in the U.S., which allows undocumented immigrants to use city services and perform other critical tasks such as opening a bank account or signing a lease.

A key conclusion in the Brookings report is that there’s an ongoing need to help hard-to-reach populations who may qualify for DACA. With legal challenges threatening the Obama administration’s reform, the report also notes that the ongoing program should be renewed.

DACA and DAPA are ultimately integration programs. They remove the fear of deportation and family separation and facilitate access to jobs, helping local communities and economies. But since they are temporary programs and can be ended at any time, it is critical that members of Congress use the experiences of these programs to design a program that offers permanent legal status to immigrants who are already on their way to being productive members of the communities in which they live.

Marielle Mondon is an editor and freelance journalist in Philadelphia. Her work has appeared in Philadelphia City Paper, Wild Magazine, and PolicyMic. She previously reported on communities in Northern Manhattan while earning an M.S. in journalism from Columbia University.

Follow Marielle .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)