In March, construction suddenly halted on a 25-unit residential complex in Philadelphia’s Old City neighborhood. No, NIMBYs weren’t protesting. There wasn’t a permit issue, or a financing problem.

There were human bones.

Workers unearthed a site where, to date, the remains of close to 500 colonial-era people have been identified: the former First Baptist Church Burial Ground, an early Philadelphia cemetery established in 1707. The story made national headlines, and people were surprised. But the members of a nonprofit organization dedicated to the protection of Philadelphia’s archeological resources, Philadelphia Archaeological Forum (PAF), know that this actually happens fairly often.

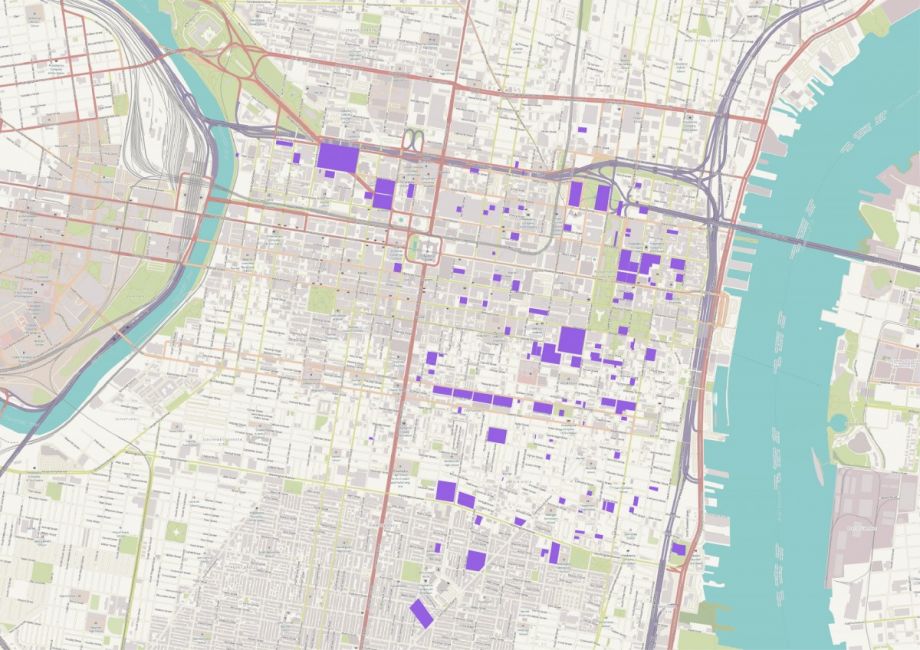

Too often, they say. As longtime advocates for those who can no longer speak for themselves, PAF is lobbying for clearer municipal laws that compel developers to handle such remains respectfully. The nonprofit also plans to release a comprehensive database with 117 historic burial grounds in central Philadelphia, with the hopes that consulting it becomes part of the planning process for new development.

Philadelphia Archaeological Forum plans to make public a database of historic burial grounds in the city. (Credit: Philadelphia Archaeological Forum)

According to research conducted by Doug Mooney, president of PAF and a member of Philadelphia’s newly minted Historic Preservation Task Force, the earliest known discovery of unmarked human remains in Philadelphia dates back to 1743. Since 1800 there have been 85 separate, documented incidents of unmarked cemeteries in Philadelphia being impacted by construction at 52 different historic burial grounds (some had repeat offenses).

Of these, 20 unmarked cemeteries have been affected since 1985 — the last time the Philadelphia Historical Commission’s ordinance was updated, granting it expanded rights to protect archaeological resources.

Cities expand over time, and this growth inevitably impacts cemeteries that were once on the periphery of an urban center. Historic burial grounds are often carefully relocated, to allow for new development that preserves urban density. In cemeteries where burials were stacked (sometimes as deep as three or four coffins), relocation frequently has not been thorough and human remains have been left behind.

The problem, specifically in Philadelphia, according to PAF, is what happens when a historic burial ground is discovered. In the absence of clear legislation and a designated law enforcement agency to ensure compliance, developers are often left to their own devices. Other historic areas of the United States, such as Rhode Island and Boston, have clear legislation in place protecting historic human remains, but in the opinion of several local archaeologists, preservationists and historians, Philadelphia’s laws are insufficient.

The current procedure, as understood by PAF, is that a developer who discovers human remains must contact the police to have a medical examiner determine whether the remains are historic or part of a more recent crime scene. If the remains are identified as historic, the property owner must petition the Orphans’ Court and present a plan for exhuming and reburying the remains. Assuming the Orphans’ Court approves the plan, the developer is then responsible for assuming the costs of excavation and reburial.

In Philadelphia, however, there is no entity endowed with the jurisdiction to enforce this procedure. “The issue on the local level is that once the medical examiner makes the determination that the remains are historical in nature, the ME has no authority to compel a developer to petition the courts,” Mooney explains. “That’s the step on the local level that’s missing: Who has the authority to compel a developer to take that next step?”

“The developer is required to do it, but the question is who is required to make them do it?” adds Jed Levin, a member of PAF working on the database of Philadelphia’s historic burial grounds, and a National Park Service archaeologist.

The city of Philadelphia maintains that legislation should be provided at the state level. According to Paul Chrystie, deputy director for communications of the city of Philadelphia’s Department of Planning and Development, “when the remains [at the First Baptist Burial Ground] were discovered, the city determined it did not have legal authority over the remains. Later, after a petition was filed by the developer, Orphans’ Court accepted charge of the case. Generally, guidance is provided at the state level, which is appropriate in that this is not an issue limited to one municipality. Given that there is no local jurisdiction in cases such as this, the [Historic Preservation] Task Force is not reviewing this issue.”The absence of local jurisdiction was demonstrated clearly this year, during the First Baptist Burial Ground case. Anna Dhody, the director of the Mütter Research Institute and curator of Mütter Museum who was part of a team of archaeologists excavating the site, attests that she found the legal procedure to be unnecessarily murky. “We were operating in, basically, a void of law,” Dhody recalls. “Nobody would tell us we could do something, nobody would tell us we couldn’t do something. It was a situation where everybody was kind of like, ‘I don’t know.’”

George Leader, another volunteer on the excavation team and a visiting scholar at the Department of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania, says, “The problem with poorly worded legislation is that there are many loopholes. The developers maintain that everything they did was beyond their legal obligation. Whether or not this is true is left up to interpretation of the law and therein lies the problem.”

PAF believes that once a cemetery is found to be impacted, the legal procedure should be exceedingly clear. “The events surrounding First Baptist are what inspired us to move this forward,” says Mooney, explaining that although the historic burial grounds database project has been in the works for nearly a decade, they were spurred by these recent events to publish their findings now.

For the time being, Philadelphia’s Orphans’ Court made an unprecedented ruling in August that the developer of the First Baptist Burial Ground site must enable and pay the expenses for an experienced building and engineering firm to map the burials, excavate and remove the coffins, and reinter the bones no later than August 2020. Another Orphans’ Court hearing will take place on Oct. 30.

It is PAF’s intention that consulting the database of known cemeteries and private family plots — the organization plans for it to be hosted on a public platform — becomes an integral part of the due diligence process for both developers and the city of Philadelphia when considering new projects. Knowing what to expect could reduce the frequency of these instances, help ensure the respectful disinterment and reburial of historic human remains at a more permanent resting place, and allow developers to plan their construction budgets and timelines appropriately.

The database, originally the personal research of archaeologist Kimberly Morrell, has been assembled from historic maps, newspapers, academic theses and other sources. Research is ongoing, but the database is the most comprehensive such resource to date.

“These are the people who built our world, and it’s a matter of human decency to show respect for those that came before us and built the city that we enjoy today,” Levin says. “What we’re talking about is not necessarily saying that you can’t ever dig in these sites. We’re saying, if you’re going to reuse this land, that you respectfully disinter and reinter. The second part of it, and it’s one of the ways that you show respect, is allowing them to tell their story through their remains.”

Karen Chernick is a Philadelphia-based freelance journalist, with an affinity for stories about people and places. Her writing has appeared on Artsy, Curbed Philadelphia, Hidden City and PlanPhilly.