Shakespeare wrote a play about it. Every major religion has rules against it. Every now and then, not nearly enough, it makes a headline or two. Predatory lending is one of the oldest justice issues in human history. In modern times, the industry comes in the form of massive, publicly traded companies with huge marketing budgets and armies of customer service representatives making the payday debt trap look so alluring that you might say it’s a perverse form of user-friendly.

The government could try to regulate predatory lending out of existence, but that wouldn’t take away the need to smooth over cash flow in situations of unforeseen circumstances like a sudden health issue, car breaking down, home in need of vital repair or countless other examples. Further, if you’re black, you have alarmingly less family wealth to draw upon in such times compared with white families. As cited recently on “This American Life,” a white person living in abject poverty in the U.S. has roughly the same ability to borrow $3,000 in an emergency as a middle-class black person does.

Capital Good Fund, a consumer lending nonprofit based in Providence, Rhode Island, is offering a new way for everyone to join in solidarity with families in such circumstances: a $4.25 million direct public offering (DPO).

It’s a chance for ordinary people to invest, not donate, to support Capital Good Fund’s work providing financial services to those who would normally only have access to capital through fringe and predatory lenders such as payday lenders, pawn shops, auto title lenders and other subprime lenders who charge families upwards of 200 percent interest on an annualized basis.

“There is just no way we are going to get $4.25 million from philanthropy in any quick, reasonable timeframe,” says Andy Posner, Capital Good Fund’s CEO.

DPOs have existed for many years in the U.S. They’ve mostly flown under the radar as an alternative way for companies to crowdfund investment from their own communities. Some have called them Do-It-Yourself IPOs. The first DPOs in Rhode Island were issued in the mid-1990s. Capital Good Fund is among the first nonprofits to take advantage of the DPO investment structure.

“One of my goals is for other nonprofits to be aware that they have this tool,” Posner says. “Obviously this is only a good tool if they have a plan for effectively deploying the capital. It wouldn’t take a lot of these going bad for the whole concept to get a bad reputation.”

Unlike standard venture or angel capital deals, DPOs are open to non-accredited investors (defined by the Securities and Exchange Commission as people with a net worth of less than $1 million or annual income below $200,000). DPOs also require minimal initial filings and ongoing reporting to regulators, especially compared with the burden placed on publicly traded companies.

One of the DPO limitations is that regulations vary state by state. So due to regulatory constraints, you must reside in one of 14 states to invest in Capital Good Fund’s DPO: Alaska, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Texas and Vermont.

The good news is, the minimum investment for Capital Good Fund’s DPO is $1,000.

“We want to make this opportunity available to average investors all the way up to high-net worth individuals,” Posner says.

Posner first learned about DPOs about a year and half ago. After coming up with a deal structure that would work for them and getting buy-in from Capital Good Fund’s board of directors, Posner says it only took about three months to go through the legal process, which included setting up a sister nonprofit to be the debt issuer.

Sixteen investors have signed up as of this writing. Some have invested as little as $1,000, while former Hasbro Toys CEO Alan Hassenfeld invested $100,000. Each investment is basically a loan, and investors may earn up to 5 percent interest. The group plans to raise $500,000 by the end of 2015, jumpstarting the work, and to raise all $4.25 million by the end of 2016.

With the investment, Capital Good Fund plans to scale up their operations in order to become self-sufficient. Only 25 percent of its revenue in 2014 came from interest payments and fees, while 70 percent came from grants. Posner expects the DPO to free them from reliance on grant support as their main source of income, giving them greater ability to scale up to meet the size of the problem.

“There just isn’t enough philanthropic dollars out there for us to become self-sufficient,” Posner says. “Basically we don’t see any other option. There’s no other way to put it. We just cannot compete with publicly traded predatory lenders on a $590,000 budget.”

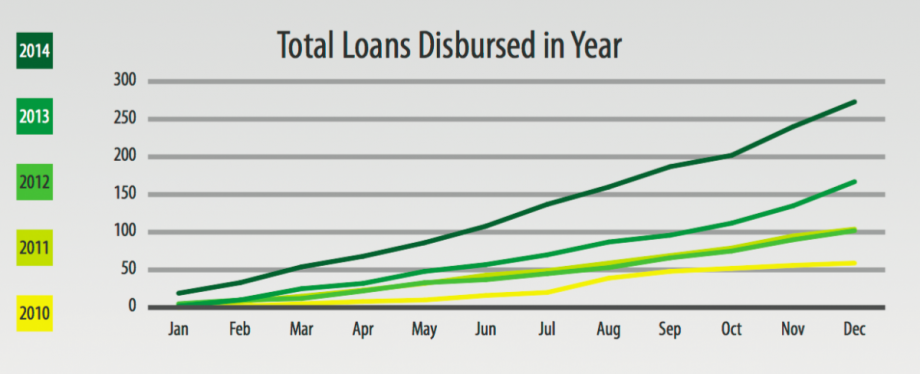

(Credit: Capital Good Fund)

Since its founding in 2009, Capital Good Fund has disbursed more than 950 loans, totaling more than $900,000 (with a 92 percent repayment rate). The DPO will enable the group to hire 60 new staff and provide 17,000 loans over the next five years (400 loans next year, 1,200 in year two, 2,400 in year three, 4,800 in year four and 8,400 in year five).

They’ll have to expand to at least one other state to meet those numbers responsibly. Delaware and New Mexico are the top candidates, based on regulatory considerations, prevalence of predatory lending in each state, and their key demographics, including immigrant populations (paying immigration and naturalization fees is a popular use of their loans).

Two big challenges lie directly ahead for Capital Good Fund. One is keeping the balance between meeting yearly growth goals and the focus on mission. In addition to making more loans and doing it in new markets, Posner says in order to generate sufficient revenue from loan repayments they need to increase their average loan size from $1,000 currently to around $3,000.

In order to maintain the balance between revenue and impact, Capital Good Fund relies on data. After loan officers process completed applications, an underwriter based at Capital Good Fund’s central office makes final decisions based on overall portfolio performance and social impact considerations. (They try to make approvals within two business days after receiving completed applications.)

“We have benchmarks for each loan product line for what kind of performance we want. We actually don’t want the portfolio to perform too well, because what that means is that we’re being too risk averse,” says Posner.

For example, on their emergency loans, the group projects a 15 percent delinquency rate. Right now they’re at 10 percent, which means in the coming months their underwriters have leeway to approve a greater frequency of emergency loan applications.

“That’s one way we can really make sure we’re balancing the business piece of things with the mission piece of things,” Posner says. As they make more larger loans, Posner expects revenue from those loans will help cross-subsidize the cost of making more smaller loans that generate relatively greater social impact.

In terms of social impact, some of the progress they reported in 2014 includes 60 percent of clients increasing their credit scores, 20 percent reducing their overall debt owed, and 30 percent increasing their food security.

The other challenge directly ahead is marketing to potential clients.

“One of our first hires with this DPO investment is a senior-level marketing person,” Posner says.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)