EDITOR’S NOTE: This story was produced in collaboration with Billy Penn and with support from Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on economic mobility. Next City and Billy Penn are two of more than 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly; read more at brokeinphilly.org or follow at @brokeinphilly.

Rachel Earnest will no longer take SEPTA into Center City because she’s not confident she’ll be able to find her way out of the underground stations once she arrives

Before the pandemic she would often take the Broad Street Line downtown, picking it up after driving to Fern Rock Transportation Center from her home in Glenside. Earnest can walk for short periods of time, but a disability makes it imperative to minimize walking.

Earnest used to rely on SEPTA to help her with this, carefully planning her trips around destinations close to stops, measuring out the steps to a bar or restaurant to ensure she could comfortably get there. In May of 2021, post-vaccination, she eagerly departed for Center City and a dose of normality. But after getting off at Walnut-Locust just south of City Hall, she found herself trapped. All the doors she remembered were sealed.

“When I got to the stop, all the obvious exits were closed,” Earnest remembered. “I ended up having to do four or five times as much walking as I had anticipated. I ended up asking some homeless guys, hey, can you lead me out of here? Thank god, somebody took pity on me and led me out of the tunnels.”

Earnest is not alone. The agency confirmed at least 10 riders have been trapped in the tunnels after walking through a one-way turnstile, only to find doors to the street barred and locked.

@SEPTA_SOCIAL I have been locked in the exit to 15th Street station (16th & Market NE Corner) for 10 minutes. I have pressed the help button twice and been told the SEPTA Police are in route.

— Dick “Kaʻa uila” Furstein (@rafurstein) January 24, 2022

How long does it take to respond?

Center City’s rail stations are connected to a vast, and confusing, concourse system that runs beneath the heart of downtown Philadelphia. As commuter and tourist traffic vanished with the pandemic in 2020, people living on the streets increasingly used the tunnels as shelter. SEPTA closed access points and cordoned off huge sectors of the underground.

“We had to harden the system, we had to close it down until people start coming back to work, and we were able to address this public health crisis,” said Ken Divers, assistant director of transportation at SEPTA and leader of the agency’s efforts to address the rise in anti-social behavior in the system.

Transit agencies are not designed to address social problems of this magnitude in the best of times, and the challenge is greater under the fiscal stress brought on by depressed ridership.

SEPTA is spending millions to contract with social service organizations to help address the issue, but the new maze of mysteriously locked doors, gated exits, and other unfriendly impediments are making the system less accessible for everyone.

“Unsheltered homelessness is having a huge impact across the board on public services like parks, libraries, transit, schools,” said Dennis Culhane, a professor of social policy at the University of Pennsylvania. “As a society we shoulder these costs and their secondary impacts on the services for the general population. It’s enormously frustrating and very expensive as well.”

Other cities also grappled with a pandemic increase in people living in the system.

In a December 2020 survey of 115 transit agencies, half said they had experienced a surge in homeless ridership. New York City’s new mayor ordered police to clear the system of encampments in an aggressive bid to attract other riders back. In San Francisco, BART stations also shuttered entrances to certain stations where people experiencing homelessmess congregated (the agency denies the closures are related). BART also ramped up spending on social services despite a looming fiscal crisis, and appointed a new “homelessness czar.”

Getting into Jefferson or suburban station is like solving an escape room

— Philadelphia Separatist (@tippedminimum) January 24, 2022

“A lot of companies are gating off their system,” said Divers, the assistant director. “That’s so vulnerable individuals won’t get into their systems to seek residence. Things have become so bad that they have to really protect the remaining riders they have. We’re not even at 50% of our pre-COVID ridership levels yet.”

There is strong momentum within SEPTA to continue the closures, to better husband cleaning and security resources. However, some riders say the lack of exits greatly contributes to a feeling of danger below ground.

Before the pandemic, Patricia Gillett rarely drove from her home in the far Northeast to her job in City Hall, usually relying instead on Regional Rail. But since SEPTA began locking down exits, she no longer feels safe.

Her job keeps an irregular schedule and the peak commuter hours, when more of the entrances are open, are often not the times she needs to ride.

“When I go to Suburban Station I encounter a maze trying to get to City Hall,” said Gillett. “I go down various corridors or go through doorways and they’re blocked. There’s a mishmash of times that certain entrances would be open. As a fairly petite woman, my fear was being cornered down there by someone who could see that I have no other way out.”

The great majority of rider concerns about social conditions stem from downtown locations, by SEPTA’s calculation, with 54% of complaints about the Market-Frankford Line referencing 15th and 13th Street stations.

Homelessness often tops the list. An email from SEPTA police chief Thomas Nestel to agency leadership gives a sense of the scale of the concern.

“We are at a critical point now where 20-30 complaints per day are rolling in and crime is rising in connection with the homeless, addicted and mentally ill,” wrote Nestel.

More signs, new guides, and “a lot to balance”

As ridership begins to return, “we’re incrementally opening back up these areas,” said SEPTA’s Divers. The agency has also been increasing the number of signs explaining entrances will be open, and when.

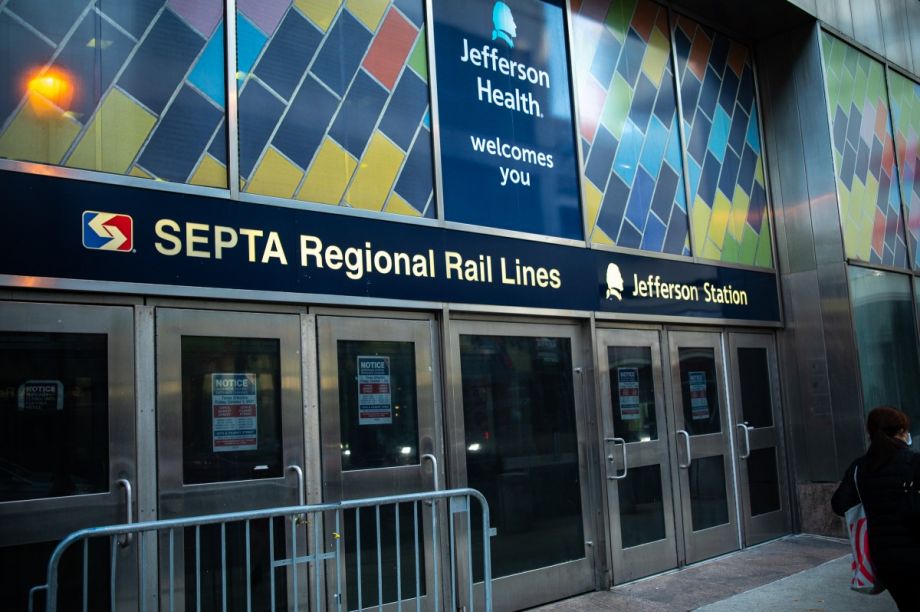

Almost every entrance into Jefferson Station is locked during non-peak hours, but they are now all plastered with instructions of how to find the on door in. Whether those signs are helpful is another question. Several riders interviewed for this article found them confusing, if less inscrutable than their absence was last year.

“In the short-term, we are looking at ways to improve signage in the concourse, and we are continually evaluating ridership, safety and related factors to determine when closed portions of the concourse can be reopened,” said SEPTA spokesperson Andrew Busch.

Busch and Divers both note that the agency has responded to rider confusion, fears about safety, and concerns about people living in the system in a variety of ways.

Last year, SEPTA contracted up to 57 social service workers to increase outreach to “vulnerable populations” at a cost of $3.6 million. In late February, the transit authority’s board voted to spend $6.7 million on 88 “guides” assigned to the two heavy rail lines and the concourses below Center City. They will be tasked with helping people navigate the system and reminding riders about basic rules. They will not be armed.

Transportation experts say SEPTA is in a serious bind. There are many reasons ridership has not bounced back, notably the increased prevalence of remote work. But the visible decrease in public order, with increased smoking and drug use on trains, trash in the system (including syringes), and encampments on the concourses also represses ridership.

The closures downtown are seen as a cheap and relatively easy way to exert control over an often chaotic environment.

“We expect transit agencies to do way too much with way too little,” said Megan Ryerson, professor of transportation planning at Penn. “SEPTA is doing outreach, has social workers, and is working with the community on the ground. They’re also shutting down entrances in order to conserve resources and to ensure safety. That’s a lot to balance for an agency who also has to provide mobility to all Philadelphians.”

The locked doors made me 10 minutes late for an hourly regional rail train out of Market East

— The Notorious S.E.B. (@bigseb31213) November 22, 2021

Thankfully the train was 15 minutes late, so I was right on time. How considerate of SEPTA!

Before COVID hit, Katarina Karris-Flores said she routinely used SEPTA Regional Rail system to visit friends in the city instead of driving in from the suburbs.

Arriving at Jefferson Station to return home after seeing a friend in South Philly last December, she tried to open the entrance. It was locked. So was the next one, and the next.

“I freaked out, I ran around the building multiple times, I checked multiple doors, and all of them were locked,” said Karris-Flores. “I saw other people were in the same situation as me, we were all trying to figure out how to get into the station that night.”

Karris-Flores found the lone open door just in time and the experience left her feeling flustered.

“It definitely made me feel overwhelmed and frustrated, because no one wants to miss a train ride to get back home,” said Karris-Flores. “I really appreciate how convenient SEPTA is, but from that instance it makes me more hesitant to go to Jefferson Station again.”

That’s the same feeling expressed by Earnest, the rider with limited mobility.

“We’re coming into spring and there are going to be beer gardens and other things to do in the evening,” Earnest said. “But I wouldn’t consider coming down to Center City now, because I have no idea if I’m going to be able to get to the streets from inside the station.”