Planning officials envision an "archipelago" of beautified neighborhoods across the city joined by ribbons of green space. One early success in the ongoing story of Detroit's revitalization is the Dequindre Cut, a decrepit rail line turned below-street-level pedestrian and bike greenway.

Photo by Amarnath via Flickr

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberRecently, Detroit has been riding a wave of feel-good stories across the urban planning landscape. In April, the city’s improved fiscal condition prompted its release from state oversight. Detroit’s central district, anchored by a stunning collection of 20th-century architecture, has boomed with recovery over the past five years. After a relentless half-century of decline, the city’s population has finally stabilized, falling by just 3,500 people from 2015 to 2016, as a rush of residential condominium construction amplifies the resurrection of Detroit’s civic corridor, Woodward Avenue. The first American city to be named a UNESCO City of Design, Detroit has also reconnected to its waterfront, setting in motion ambitious reconfigurings in both the northeast and southwest that have a decidedly international flair. If those expanses of sculpted green space arise as planned along the river, future visitors may see hints of Oslo and Copenhagen at the water’s edge.

Downtown’s looking solid. What about the rest of the city? In January, Maurice Cox, director of planning and development, and his central district director, R. Steven Lewis, attended a jam-packed workshop at the University of Michigan titled “The Other Detroit,” a forum devoted to the concerns of African-American women. (For more on Cox and Lewis, see Next City’s profile of the pair.)

“It was the kind of conversation you would have in your living room,” says Lewis, who watched his colleague make his way through the crowd. “And it was confirming for us to hear so many say how ‘unusually refreshing’ it was to have a partner on the municipal side, for the neighborhood residents who’ve been here, through the thick and thin.” Lewis, an architect by training who has broad public and corporate development experience, shows confidence in the durability of the downtown resurrection. But he is eager for that recovery to extend to the rest of the city.

Their plan? To engage the community and work quickly. “In a certain sense we are working under a time clock,” he says. “We are just emerging to the point where we can issue bonds. And we have to be careful and not assume everything is trending positive.” In the event of an economic downturn, typical of every business cycle, Lewis speculates whether “downtown could forever be ok, but then the neighborhoods surrounding it could be as unchanged as they are today.” If that happened, Lewis continues, “We’d all be failures.”

Both Cox and Lewis did advocacy work in New Orleans right after Katrina, and are deeply committed to nurturing a sustainable recovery in Detroit. Downtown may be polished into a shining jewel, but the task is to bind Detroit together again — to repopulate neighborhoods with residents who bike or take transit to work downtown, instead of commuting outside Oakland County every day. Lewis teaches a course called “Designing With Community” at Michigan’s Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, and he cites the Latin phrase nihil de nobis, sine nobis — nothing about us, without us — as the mantra coming from neighborhoods. Within this sentiment are the seeds of what a real recovery might look like.

Conversation about the city’s future often boils down to the phrase “The Two Detroits,” which juxtaposes the heady rush of private investment gushing through downtown with the longer-timeline revitalization inching forward in the rest of the city. During this recovery, there’s been growing sense, especially among Detroit’s longtime residents, that a resource shift is taking place that unfairly favors the business district. That’s understandable. But the trajectory of this growth reflects Detroit’s history, rather than any contemporary policy. As a large legacy city, Detroit has an oversupply of underproductive land. As a city that came of age in the 20th century, Detroit has been carved up by highways and overbroad surface streets. As a post-industrial city, it situated residential neighborhoods far from places of employment. Detroit pursues its recovery on the platform of this history — one that encourages, but also hampers, its current attempt to fly.

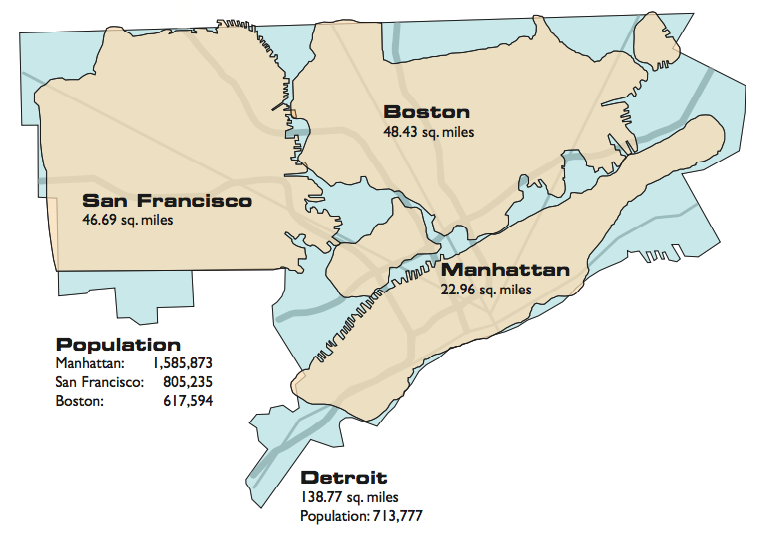

Back in 2005, during his time as a Loeb Fellow at Harvard, Maurice Cox saw an unusual map of Detroit. Cox, who had spent more than a decade as a professor of architecture at the University of Virginia, was coming off a term as mayor of Charlottesville, UVA’s hometown. The map fascinated Cox. Created by Loeb Fellow Dan Pitera of the University of Detroit at Mercy, the map depicted Detroit as a container of other cities, large enough to hold the footprint of Boston in Detroit’s northeast, San Francisco in Detroit’s west, and the whole of the island of Manhattan running the course of Detroit’s lengthy waterfront. Looking at this map with the glass half full, this trio of cities-within-a-city overflowed with potential: a new Detroit of forested villages, with room for urban agriculture, planted meadows, and a restored downtown. The glass-half-empty view? After decades of relentless depopulation, Detroit’s 139 square miles were wrongly scaled for governing. Detroit was just too big.

Dan Pitera's map of Detroit, showing the city as a sprawling container big enough to encompass the areas of Boston, San Francisco and Manhattan. (Credit: Dan Pitera, Detroit Collaborative Design Center, University of Detroit Mercy School of Architecture)

The map was a foreshadowing for Cox. Ten years later, in the Spring of 2015, Cox became the director of planning for the city of Detroit. Today, Cox presides over an energetic Detroit planning department, recruiting architects, designers, historians and planners from all over the country, and from as far away as Australia. They organize strategy largely along the lines of those same three regions: Downtown, East and West. And Cox has successfully marshaled professionals to the cause of Detroit, in part, because of the city’s rich set of design challenges.

For one, the local workforce does not align with the region’s job opportunities. Not only do two-thirds of Detroit residents commute to work outside the city each day, but according to Deputy Planning Director Janet Attarian, two-thirds of Detroit’s downtown workforce commutes from outside the city limits to work each day. This polarization was compounded over time, exacerbated by decades of disinvestment, and will need effort to repair. Thomas J. Sugrue’s seminal “The Origins of the Urban Crisis,” for example, details how building permits for factories and shops began to decline, precipitously, as early as 1953. Jobs are far-flung in the region today, therefore, because industry itself has become so far-flung. Navya, a French manufacturer of new AV minibuses, did not choose Detroit, or Dearborn, or even Ann Arbor to set up shop. They picked rural Saline, Michigan, forty miles to the west. You can begin to appreciate the work that lies ahead to remake Detroit.

Some urban theorists speculate that Detroit’s deeper agricultural past has experienced a rebirth. In the 18th century, Detroit was partly composed of ribbon farms growing pears and other fruit, farms that advanced in long, narrow tracts inland from the Detroit River. In many outlying sectors, the city feels pre-industrial once more. Urban agriculture — the appearance of small plot farmers and larger operations such as apple orchards and cider makers — reflects a burst of energy that has emerged since the great recession, when you could buy houses and land for less than $100.

Kimberly Driggins, director of strategic planning for arts and culture, sees these land-based businesses as rich assets that could be amplified for broader renewal in Detroit’s less dense areas. “Interestingly, urban agriculture, historic preservation, and arts and culture are three elements that are often intertwined,” she says. “So you take something like the Heidelberg Project, and that becomes a way to pivot, and actually start thinking more broadly, about a development strategy that is land-based, art-based.” Driggins’ approach has been to identify existing assets in outlying neighborhoods — iconic, historic buildings that anchor a community or upstart farm and art organizations, for example — and find ways to save and nourish them.

As Cox’s planners reckon with Detroit’s surplus land, they see positive developments. First, the demolition phase of Detroit’s decline — when it was better to plow down vacant buildings than to let them stand — has finally slowed down. Second, the general price of land and real estate has stopped falling, and in some areas has started to rise. The assessed value of property in the city has risen for the first time in 17 years. For Driggins and other historic preservationists, it’s a signal that Detroit’s built environment has begun to stabilize. Now, existing buildings, many of which are candidates for adaptive reuse, can be brought back, even if slowly.

Cox recruited from Australia the well-known landscape architect Elizabeth Mossop to address Detroit’s immensity of acreage. What might the future be of this great expanse? The word archipelago comes up often, in conversations with Cox and others, to describe a network of beautified neighborhoods joined hand-to-hand by ribbons of green space. In addition to agricultural businesses, Detroit might also choose to deploy solar and wind farms.

Cox’s multi-disciplinary teams are pursuing a clever neighborhood revival strategy that activates local artists, universities and entrepreneurs. “Without the ideas that flow directly from people in the neighborhoods,” Cox explains, “we can’t come up with sustainable solutions. The residents themselves hold the key.”

This approach says something important about how local economies are remade. Importantly, this startup-like group of urban innovators opposes dropping into neighborhoods and imposing solutions cooked up down at the planning department. Instead of huddling in conference rooms, members of Cox’s planning department are on the street conducting face-to-face meetings and workshops. They have one question: what is the change you’d like to see?

Dave Walker, director of the West region of Detroit, is cultivating a revival of two neighborhoods, Livernois McNichols and Fitzgerald. The ultimate goal? “We want these neighborhoods to become the jewels of Detroit,” Walker says. “And hopefully, to attract people back to the city.” How will it happen? Walker explains the layer by layer approach: start first with community engagement, build on a district’s existing “good bones” and send out signals of change that attract entrepreneurs and foot traffic. “The nice thing about Livernois McNichols,” says Walker, “is that it already starts with a strong corridor, with a branding called The Avenue of Fashion. And this is what we heard from residents, that back in the day, everything you needed you could get in that corridor, without having to go to downtown. So it has a great legacy around it.”

The proposed redevelopment of Livernois Avenue, Detroit's historic “Avenue of Fashion,” encourages human-scale traffic with wider sidewalks, clear signage, and bike lanes. (Credit: City of Detroit)

Probing the lived experiences and memories is the first, crucial step. This engagement process ultimately leads to an important moment when the community buys in to the changes. That can only happen if residents see themselves as having a hand in that change. “The existing residents, and their history, and being a promoter for them, is where all this begins,” says Walker. “They just want simple things, like to be able to walk out of the house, go down to the main street, and have a nice meal”.

Next comes building hope and expectations. For example, the planning department has publicized beautiful renderings of how the neighborhood’s central spine, Livernois Avenue, would look after a series of contemporary design changes you might recognize from cities such as Portland or Boston. Sidewalks are widened, parking slightly reduced, intersections pinched, bike lanes added, and it all gets planted up with trees. Speed bumps may be added. Fresh signage is also important — brightly painted crosswalks, stop signs and other safety additions. What do residents want? Safer streets, where kids can ride bikes without worry. The planning department must deliver these outcomes.

Once the community has been heard, and they understand the city’s plans for the corridor, the first wave of entrepreneurship appears, usually small retail shops and cafes. “That entrepreneur who has always wanted to start a restaurant, says, ‘Hey I want to get involved.’ So they start to contact the Detroit Economic Growth Corporation (DEGC), or Motor City Match. And that’s exactly what you want to see happen,” says Walker. Kuzzo’s Chicken and Waffles, at 19345 Livernois Avenue, is an early pioneer and it brings all of the design traits — modular, large glass windows, contemporary use of wooden siding and solid color — that you’d see in a San Francisco or New York cafe. “The ultimate goal is to create a buzz, and to have these neighborhoods become destinations,” says Walker. Sure enough, more restaurateurs have started to focus on the district.

Here’s the clever approach of the planning department’s neighborhood cultivation: the City of Detroit hasn’t started actual street work yet on Livernois Avenue. That will start later this year as the city distributes the funds from a successful $125-million bond targeting such corridors. Indeed, Detroit’s exit from state oversight of its finances clears the path for additional municipal borrowing. The aim, Walker points out, is to spark growth organically. Get residents involved before the big road project actually lands. When the streetscape improvement arrives, which Walker refers to as the activation, the community will (rightly) feel they were part of the process.

Designing with community (to use the title of Steven Lewis’s course at Taubman) also has the potential to address Detroit’s fundamental land-use problem: how to creatively repurpose so much surplus land. Mossop’s solution for the Fitzgerald neighborhood illustrates how to creatively re-establish clusters of single-family homes, while corralling so much green space. Her plan echoes the ribbon farms of Detroit’s past.

A rendering of Ella Fitzgerald Park, in the Fitzgerald neighborhood, a two-and-a-half acre green space formed by connecting reclaimed residential lots—one approach to holistically integrating Detroit's surplus land. (Credit: City of Detroit)

Cox tells a poignant story of how a comprehensive solution is coming together in Fitzgerald, where a new park and community center broke ground this past October, part of a larger neighborhood revitalization. “At the center of this neighborhood, we proposed to cluster together several parcels of land to make a two-and-a-half acre park that would extend across streets and across alleys,” he says. “This is the first time we’ve ever tried this, to see if you could make a central, neighborhood park wholly out of formerly residential parcels adjacent to each other.”

“We tried hard to figure out how to make this park culturally meaningful to the neighborhood,” Cox says. “And to our delight, in one of our community meetings, residents said ‘We’ve decided to name this Ella Fitzgerald Park.’ And they explained why: there is a local elementary school named Bethune Academy — and before it was Bethune, it was Ella Fitzgerald.”

The story continues. “Not only did the community figure out how to rescue the meaning and the memories from a school they could not rename, but the residents told us ‘We also want a way to put the handprints of kids, all over the park.’” Cox calls this a type of cultural tagging. For change to endure, locals must take ownership of those changes. What was the solution? To partner with a local African American artist, Hubert Massey, who will create a ceramic tile mural in two 80-foot segments — 160 feet long in total. The mural contains the handprints of children, another level of tagging that also taps the memories of children who once attended the Ella Fitzgerald School. “The fingerprints of the neighborhood will literally be all over that park,” Cox says.

No one institution can steer the next phase of Detroit’s recovery. The city has inspired a unique legion of civic entrepreneurs — a do-it-yourself necessity that emerged from the city’s nadir. And Cox, Lewis and others in the planning department (as well as those in the Mayor Mike Duggan’s office) have proven to be leaders who are willing to learn. Detroit Greenways, for example, led by Executive Director Todd Scott, has spent years stitching together a different kind of road map composed of bike lanes and trails. The organization was active through the roughest patches in Detroit’s economy, and their highest-profile initiative to date, The Dequindre Cut, is an astonishing transformation of urban ruin to welcoming public space. As a former rail line, The Cut has been recognized as part of a national network of similar public-space transformations, among them New York’s completed High Line and Philadelphia’s emerging Rail Park.

The Dequindre Cut is a wonderful example of a proofing concept that began as an experiment and became incorporated into everyone’s understanding of how to make Detroit grow.

Scott tells of a pivotal meeting in early 2016, when Janette Sadik-Khan, author of “Street Fight,” gave a data-rich, thematically persuasive presentation to the mayor, his staff, and the planning department. Known for her work in pop-up parks and in bike advocacy in Manhattan, Sadik-Khan explained that bike infrastructure wasn’t just for cyclists. Instead, the introduction of bike infrastructure was the leading edge of the change you want to see in the crucial process of humanizing streets. The Mayor called a meeting two months later to say he was on board with the idea, and bike lanes are now considered a crucial part of the human ecosystem Detroit’s streetscapes so desperately need.

Attarian cites the Dequindre Cut as a wonderful example of a proofing concept that began as an experiment, then became incorporated into everyone’s understanding of how to make Detroit grow. The Dequindre Cut is now a backbone in a much larger bike arterial already coming together, piece by piece, for the newly named the Joe Louis Greenway.

Another feature of the Dequindre Cut deserves highlighting. The wisdom of the layered, step-by-step process now pursued in the neighborhoods is designed to attract a wave of future stakeholders. And The Cut, once an abandoned trunk line, now serves as the magnet for the next layer of investment. Two design proposals, part of Design 139’s collaboration between the city and Taubman College, would capitalize on The Cut’s position within Detroit’s grand cycling circular. The design for both The Sky Bar, a public space, and Urban Balcony, a residential project, leverage the new green corridor’s unique position as a below-street-level piece of public infrastructure. For a city looking to bind itself back together, shared public space is crucial. ”Detroit is in a period where we are transitioning from an interior focus, insular, from the four walls in,” says Lewis, “to encouraging people to focus outward, to that public realm.”

For years, urban planner delegations have made pilgrimages to cities such as Amsterdam and Copenhagen to study how to reconnect cities to waterfronts and nature. Essen, Germany and Pittsburgh have been studied for ways to remake post-industrial cities. What if Detroit is poised to become the newest teaching story?

Esther Yang, design director of Detroit’s East region, was recruited from the J. Max Bond Center (JMBC) in New York; their 2015 study, Mapping America’s Legacy Cities, was intended as a way for post-industrial cities to learn from each other. Yang works with neighborhood communities such as Jefferson Chalmers and keeps the conversation active between the planning department and the DEGC, which fosters industrial development. Yang cites the recent Flex-N-Gate project in the I-94 Industrial Park as the recent success of both design and community engagement — proof that a manufacturer coming back to Detroit was willing to yield to community concerns. Yang has a great interest in data and would like to use tools she helped to develop at JMBC to measure actual progress of social justice. “If you don’t listen well, you won’t design well,” she says. If Detroit, as recovering legacy city, embraces the data charting its own progress, it could become a template, producing volumes of replicable knowledge.

If Detroit re-emerges as a place of cutting-edge design and a laboratory for post-industrial healing, where a sturdier, more rooted recovery is taking place, that suggests recent outbreaks of optimism are only now catching up to the city’s considerable forward momentum. What’s also clear: the direct connection between community-centered planning and a truly enduring economic recovery. When Maurice Cox says, “We are here to serve those residents of Detroit who bravely stuck it out, to serve those who stayed,” Cox is talking about the rebirth of civic thinking. Newly aware of its own strength, Detroit sends out an important signal.

Gregor Macdonald is a freelance journalist covering urban development, climate, and the energy sector. He has written for Nature, The Economist Intelligence Unit, Atlantic Media’s Route Fifty, and Talking Points Memo. He is based in Portland, Oregon.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine