Every year, when temperatures fall, the urgency rises for Erica Strang and her team of street homeless outreach workers. Around 4,000 people sleep each night on New York City’s streets, subway platforms and entrances, or other public spaces. The cold months bring the threat of hypothermia, frostbite, and other cold-weather maladies.

As street outreach director at the Center for Urban Community Services, Strang’s team is part of a citywide network of outreach workers tasked with knowing where those 4,000 sleep every night, checking in with them as often as possible, getting them emergency medical care when needed, and eventually getting them into stable and hopefully permanent, supportive housing. Strang started out in 2006 as an outreach worker herself, and now oversees a borough-wide team of outreach workers in Manhattan.

This winter is different. For the first time, the citywide street homeless outreach network went into the tough winter months with a single, unified, custom-built case management system. It’s called StreetSmart, and it was put in place this past July.

“Being able to have a system that is catered to our needs is really great, and so is being able to have a say in how it works,” Strang says. “If we think there needs to be an improvement or to do something differently, [NYC’s Department of Homeless Services] is able to incorporate that into the system. ”

The process that led to that customized case management system also resulted in a series of changes in the way the city’s street homeless outreach network works.

That process is known as public service design. A growing number of cities — like New York, but also Philadelphia, Louisville, Denver, and others — as well as federal agencies are making use of the tools, methodology, and trained professionals that are part of the emerging field of public service design. It’s helping agencies and governments become more efficient, reforming or replacing old ineffective programs with evidence-based, user-tested solutions. It’s helping agencies become more responsive to changes on the ground as they arise. It’s opening up new conversations about how government works, bringing fresh eyes to old problems, and even fostering new relationships that are starting to result in key policy changes.

Mapping the way home

When Ariel Kennan first came to work at the Mayor’s Office for Economic Opportunity, part of the NYC Mayor’s Office of Operations, she found herself feeling a little lonely. There were only a few other graphic and user-experience designers scattered across NYC’s 300,000 city employees. She didn’t have her trusted digital sidekick—the design software she had grown accustomed to using as a student at Parsons School of Design.

“We didn’t even have [Adobe’s] Creative Suite when I started. None of the tools were here in order to work this way,” says Kennan, now director of design and product at the center.

Things started ramping up, and fast, in December 2015.

A couple years into Mayor de Blasio’s administration, the city’s homeless numbers were at record highs. While the vast majority of the city’s 62,000-plus homeless individuals are in city-funded homeless shelters, the 4,000 or so street homeless persisted even as the city ramped up funding for shelters to over a billion dollars.

What was going wrong? Why were so many individuals remaining outside? Nobody really knew. A lot of folks had a lot of opinions, but no one had mapped out the entire process of identifying a street homeless individual all the way to getting them into permanent housing.

That December, the mayor announced the Homeless Outreach & Mobile Engagement Street Action Teams (HOME-STAT) initiative. Then he turned to Ariel Kennan.

“We got called in immediately after that press release,” Kennan says. “As we started talking to people, we realized that people knew a lot about what their agency did as part of the process, or their particular program, but not the whole service from end to end.”

DHS contracts with seven nonprofits to manage homeless outreach. Kennan’s team eventually did interviews or focus groups with 37 government staff, 28 program staff at partner organizations, and 7 homeless clients. They shadowed street outreach workers to understand their processes and observe their interactions with homeless individuals and city agencies — including accompanying some workers on overnight shifts. They also spent time at the city’s social safety net agency to observe part of the process homeless clients and their case managers may go through to place them in permanent housing.

And they were doing all that through the busy winter months for street homeless outreach workers.

“We’re finding that design is incredibly empowering to a lot of people who might not have had as big a voice in making decisions or fighting for their program and getting the attention it deserves,” says Kennan. “We do not enter that space as if we know everything about this, we enter it with a different skillset.”

That skillset is the design skillset. Design is about more than just how things look — it’s about how things work. It’s about making things operate so smoothly you don’t even notice when you’ve spent a whole day binge-watching episodes of a favorite TV show.

The design skillset is more often applied to things like building the next billion-dollar app, but a growing number of designers have been looking for projects, clients, and positions outside of the usual corporate powerhouses.

“I think there’s been a migration of interest and a re-orientation of what people want to be doing with design that’s actually meaningful, not just delivering products to consumers but actually solving complex problems,” says Emily Herrick, the newest designer on Kennan’s team, hired in September. “Designers are attracted to complexity, and the public sector is full of it.”

There’s another reason designers are so powerful. With no clear stake in the outcomes of the discussions, designers can more easily push back or push forward with less chance of being accused of bias. “One of the things we heard was the outreach workers need to do a better job, they must not be doing as good outreach work as they could be doing,” Kennan says. “So we went to spend a lot of time with outreach workers, who were amazing people, absolute heroes working on the street everyday. Their job is very hard, and it’s just simply that there were not enough of them.”

In response, the city doubled the funding for outreach workers, upping their numbers across the five boroughs from 191 to 387. It wasn’t exactly a new idea; the nonprofits that do this work are chronically underfunded and understaffed. But when the city responded to that call, the response came as part of a broader, comprehensive narrative.

“We were able to change the narrative, to be less focused on [the outreach workers],” Kennan says. “We got increased funding for more outreach workers, and then we started looking at where are people actually getting stuck in the process.”

The case management system, known as StreetSmart, was also part of the new narrative. StreetSmart allows the nonprofits doing outreach to homeless individuals on the streets or in the subway system to track every person whom they’ve contacted in one system across all seven nonprofits. If someone moves from one borough to another, the nonprofits can easily coordinate using the first ever “by name” list, a list of names that each street homeless individual goes by. (It’s closely guarded for privacy reasons.)

The shelter system isn’t a good fit for some, and many homeless individuals openly avoid the shelter system at all costs for reasons like its spotty track record on physical safety and humane conditions. The city has developed other pathways into permanent supportive housing for such individuals, and it’s also on the street homeless outreach teams to guide those individuals along that path. For the first time, thanks to the service design process, the street outreach teams have multiple ways in digital form and in real life to track client progress along that path and hand off clients to each other seamlessly as needed.

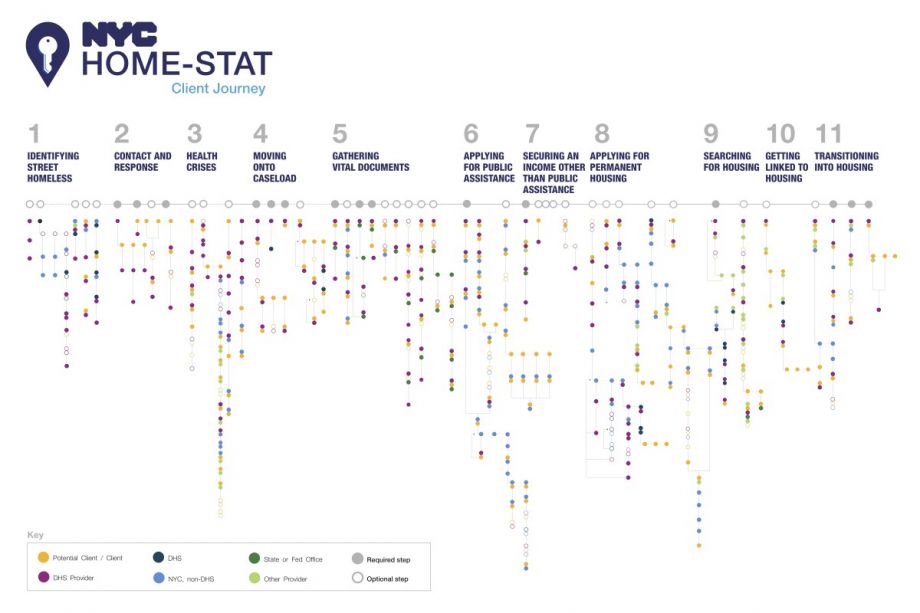

(Courtesy NYC Service Design Studio)

Previously, the street homeless outreach teams used a combination of the city’s case management system for homeless people in shelters and their own ad hoc systems. Since it wasn’t designed for them and couldn’t be rapidly adapted to their needs as issues arose, the many inadequacies and inefficiencies of that set-up exacerbated the problems of already being short-staffed. But after being mislabeled as the bogeymen in the process at the outset, the street outreach workers suddenly became the center of the process.

Nathan Storey, another staff member in the Mayor’s Office of Operations, came into the picture in April 2016 to implement some of the ideas Kennan’s team had surfaced, including StreetSmart. Storey’s first big task was facilitating the design process for the case management system. That process included healthy feedback and user testing with outreach workers.

“We established a way of working where we were listening to the end users and continued that into the development process,” Storey says. Another key change was implementing a monthly case conference meeting, bringing together DHS and the nonprofit providers to discuss bottlenecks and follow up on clients. Different agencies may also be invited, like the Department of Corrections or Department of Health, to discuss individuals who may be released from jails or hospitals and may end up back on the street.

The providers have internal ways of tracking some of those events, and have continued to use some of them, but they’re fading out as StreetSmart begins to take hold and DHS is able to continue adding or changing features to fit outreach workers’ needs. The monthly case conference meetings provide a regular, ongoing place to follow-up on issues with StreetSmart or any other issues bubbling up at the ground level.

“The ability for street outreach providers to have our own system designed specifically for our work is significant,” Strang says. “The detailed information it provides us along with the ability to easily communicate with fellow providers with StreetSmart is helping us all better serve our clients. I think we can see that even in the first 6 months.”

Kennan's team mapped out the client journey from sleeping on the street to transitioning into housing. There were a number of steps involved, to say the least. (NYC Service Design Studio)

Kennan’s team, meanwhile, moved on to the next big project — officially launching the NYC Service Design Studio, formalizing their role in the city to help other agencies adopt public service design practices and invest resources in design. They created a service design guidebook, and will be vetting a pre-qualified list of vendors who can provide design services to city agencies. They’ll also work with agencies to identify and interview designers for projects or even for hire as full-time city agency designers.

“HOME-STAT was huge for us,” says Kennan. “It was the first project where we came in and got to do the full end-to-end service design, with a team around it. That started getting people to recognize there was a new resource to help think through stuff, and we got to start delivering work and building a reputation among other peers in the city.”

Unexpected changes

When Chelsea Mauldin’s nonprofit, Public Policy Lab, began working in 2012 with NYC’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD), the agency did something quite unusual: It didn’t give her any specifics.

“We started with an extremely wide open brief — how do we improve the delivery of affordable housing services for New Yorkers,” Mauldin says. After mapping out HPD’s work as an agency, similar to the way Kennan’s team would later map out the street homeless to housing process, HPD decided to focus on the housing lottery process, a source of much frustration for the agency as well as New Yorkers in need of affordable housing.

Whenever a city-subsidized building begins to rent out new units of affordable housing, HPD runs a lottery to hand out those units to qualified tenants according to income levels. But the process has historically been confusing and inefficient. People with incomes too high or too low for certain units apply anyway—70 percent of the time, according to Mauldin. The agency only accepted paper applications. Then, for those fortunate to win a lottery, they usually didn’t realize that they hadn’t won placement in the unit—they’ve won the right to apply. They might still get disqualified or rejected by the landlord during the leasing process.

Public Policy Lab, which recruits fellows from the design world to work on projects like this one, devised and tested an ambassador program to support nonprofit service providers responsible for informing residents about HPD’s lotteries. The ambassador partners were equipped with newly designed communications and marketing materials. Applications can now be filled out online. From just a handful of ambassadors at the start, there are close to 30 and counting today. HPD used to do two or three public events each year tied to housing lotteries; Mauldin says they now do two or three a week—not exactly groundbreaking, but it took a service design process to put it in motion.

But the most important change didn’t become apparent until several years after.

“Only now after two or three years we are seeing the most profound ripple effects of this work,” says Mauldin.

With a much more active back-and-forth relationship between HPD and the ambassador providers, Mauldin says HPD started hearing more from those organizations about other snags in the process. Those discussions, Mauldin believes, are what led to HPD announcing last fall that developers and leasing agents would no longer be allowed to deny affordable housing tenant applications based solely on credit scores.

“That, to us, is incredibly powerful,” Mauldin says. “You can build channels that allow agencies to do policymaking informed by community engagement and community feedback that isn’t always in the contentious environment of a public meeting. You can build a working relationship that allows you to get ongoing news from the ground that helps you deliver better policy or better services.”

Small world, big change

In 2012, Liana Dragoman was a design fellow on that HPD project with Public Policy Lab.

“That was the first time I thought shifting my attention and my focus to the public sector made a lot of sense,” Dragoman says. “I started to take on more projects working with governments, foundations and nonprofits.”

Living in Philly at the time, the whiplash of train rides up to New York or down to D.C. for projects or client meetings eventually got to be a little too hectic. Dragoman started looking for jobs at home. In the meantime, new Philly Mayor Jim Kenney had made a commitment to improve services, make them more efficient and improve interaction with the public. He needed a designer.

Dragoman came onboard as Service Design Practice Lead and Deputy Director of Philadelphia’s Office of Open Data and Digital Transformation. Together with Anjali Chainani, Director of Policy in the Mayor’s Office of Policy, Legislation, and Intergovernmental Affairs, Dragoman has spent the last year or so leading her peers in city government on a tour of service design concepts and case studies. They started an ongoing speaker series, featuring Mauldin at one of them.

“We had a really wide range of colleagues from different departments who attended, from the mayor’s office of education, adult education, operations, health, parks and rec,” says Chainani. “Some of the really useful workshops we had were around how to describe problems accurately and how to bring various stakeholders to the table to start identifying solutions.”

In November, the city announced the two first winning proposals to be part of the PHL Participatory Design Lab. With support from a Knight Foundation Cities Challenge Grant, Dragoman and Chainani hired two fellows to work with Dragoman and Chainani on a pair of projects both tied to housing — examining the Office of Homeless Services’ intake system, and the Department of Revenue’s Owner-Occupied Payment Agreement program, which assists homeowners behind on their real estate taxes.

Dragoman is eager to see how her colleagues in other agencies begin to respond when given something concrete to put design tools to use.

“A lot of the colleagues that attended those sessions are day-in and day-out experts in content and delivering services and how those things work and also how they don’t work,” Dragoman says. “Giving people tools to effectively frame problems at hand and giving them tools and methods to do something with that opens people’s eyes up to how they can, on a day to day basis, make things better for residents.”

In the meantime, back in NYC, the Design Studio recently released an open call for partnerships, called Designing for Opportunity, to other city agencies, looking for its next big end-to-end service design challenge to solve. They’re also offering office hours, on Tuesdays and Thursdays, when agencies and nonprofits can make an appointment to discuss a challenge with the team at the studio. Through the Mayor’s Fund to Advance New York City, the lab has been able to hire additional designers and fellows without having to go through the hefty bureaucratic process of adding new city employee positions. Citi Community Development provides funding for the design studio through the Mayor’s Fund. (Citi Community Development also provides funding to Next City).

Mauldin, meanwhile, continues advocating for and bringing service design to other cities, like Louisville, where Public Policy Lab looked into the question of how a jail can provide support to break the cycle of opioid use and incarceration.

“In some ways, the specific design outcome of any given project, we are coming to believe, is not the most meaningful deliverable,” says Mauldin. “We work with partners to respond to a need, but the most meaningful systems change comes from providing people with an opportunity to see how they can create policy and engage with the public in a different way. They take the lessons from the work they do with us and they apply it to other stuff.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: We’ve corrected the name of the NYC Service Design Studio as well as the Mayor’s Office for Economic Opportunity. We also updated the status of the Designing for Opportunity call and clarified that the Public Policy Lab ambassador program for HPD recruited nonprofits, not individuals.

This article is part of The Bottom Line, a series exploring scalable solutions for problems related to affordability, inclusive economic growth and access to capital. Click here to subscribe to our Bottom Line newsletter.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)