Shadrack Frimpong tends toward understatement. The University of Pennsylvania undergraduate was born in Tarkwa Breman, in Ghana, to a family below the global poverty line. “My mom is a charcoal seller,” he explains, his father a smallholder farmer. “My parents are really, really poor.” Yet the 22-year-old will cross a commencement ceremony stage next month — and then return to his village to build a clinic, using a $100,000 grant the university awarded him.

Frimpong downplays the rarity of his leap from informal child laborer to Ivy League graduate and nonprofit founder, calling it “probably an unlikely trajectory.” It is — and yet there are other achievers like him. Collectively, they offer insights into how bridging the gap between informal workers and international donors might produce best results.

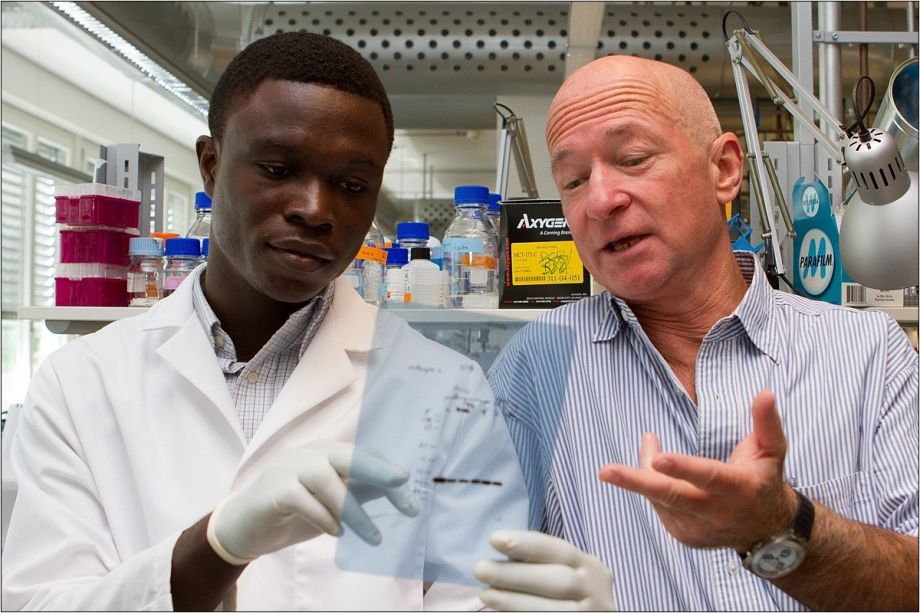

Ghana’s meritocratic educational system was a good starting point. “You can be very poor, but if you pass the national exams, you can get in … to a very good high school,” he says, describing how he transitioned out of working as a child street vendor. In high school, teachers recognized his potential and encouraged him to take the SATs; five years later, he’s set to graduate with degrees in biology and global health and has completed medical research fellowships in Switzerland and Botswana.

For all this illustrious experience, he hasn’t lost his connection to home. “My family is still back there,” he says, in the same conditions he grew up in.

Those conditions include serious vulnerabilities. His small hometown, Tarkwa Breman, is close to gold mines in the larger town of Tarkwa. The mines’ male-only workforce flows through the impoverished village, and their transient, transactional trysts have created an HIV epidemic far more intense than Ghana’s national prevalence of eight cases for every 1,000 people. Death, Frimpong says, is never far away in Tarkwa Breman. The crisis has granted him clarity of purpose: His general practice clinic will help address the local burden of AIDS.

He also hopes to augment this with a female-only school. “I’ve realized that education and human health are … inextricably linked, and I became very interested in women empowerment,” he says. “In Ghana, in my village and in many rural areas in Africa, we don’t put emphasis on girl child education. That is something I really didn’t want to tolerate.”

In this, he echoes another member of the small group who vault from developing-world poverty to elite status in the West in a few short years: Terarai Trent, a Zimbabwean woman who endured an impoverished childhood and early marriage to an abusive husband before completing a Ph.D. and launching an Oprah-boosted initiative to educate African girls. (“You can have nothing, come from nothing, and still become everything you dream,” Oprah Winfrey has said about Trent’s example.) Trent serves a demographic she once belonged to, and, citing her own life, promotes the transformative power of education. Frimpong does much the same.

Professionals like Frimpong and Trent can be especially well-positioned to accomplish goals that require working with people on both sides of vast gaps in income, culture and education. Mosoka Fallah, a Liberian who lived in a Monrovian slum called West Point in his childhood, provides an especially compelling example. When Ebola hit Monrovia last year, the Harvard-trained epidemiologist and immunology Ph.D. helped organize one of the crisis’ most effective responses: community volunteers who sought out the ill and encouraged appropriate care and quarantine. While the government attempted unpopular, repressive methods of infection control, Fallah used his familiarity with the community to promote cooperation. He told the New York Times it was crucial to results: “If people don’t trust you, they can hide a body, and you’ll never know … And Ebola will keep spreading.”

Because of his professional experience in wealthier nations, Fallah was also able to negotiate with the community, government and international donors to fund salaries, allowing these informal healthcare workers to continue their efforts for months.

Frimpong says the Ebola crisis is an excellent example of how goals can be achieved by marshaling the existing community’s innate capabilities, and like Fallah, he orients his work to combine community members’ contributions with international support. Acknowledging that funding will be “one of the most serious constraints of the project,” he’s arranged for the community to complement the Penn grant with volunteer construction work on the clinic and school buildings. “The people come together to do everything. It’s like a communal holiday. You all work hard and get it done,” says Frimpong, describing a system in common use across Ghana. “Their own houses, whatever, they built it through communal labor.”

After the clinic opens in July 2016, Tarkwa Breman’s population will continue to contribute to clinic funding — although largely not through individual payments for care. Rather, Frimpong has arranged with the local chief for the proceeds from the sales of crops raised on a designated piece of land to benefit the clinic. This collective arrangement is also traditional, he says: “They’re doing something they’ve done for ages.”

The bridging of informal and formal approaches must extend well past finance, Frimpong says. “If I become a doctor and go back to my village, and there’s a traditional healer, guess what? People will be trooping to the traditional healer … [who] has been able to take care of them over the years,” Frimpong says. He cites the prospect for Ministry of Health officials to use the clinic as a location for health education sessions for laypeople, and adds, “You can provide the traditional healer with the training to work more efficiently.”

While he cites neither by name, Frimpong often echoes the perspectives of Trent and Fallah. All three assert the innate abilities of people poor enough to be locked out of the formal economy.

“One thing I’ve realized is that the people in the community, some of them have the answers,” Fallah told the New York Times.

“Extraordinary things can happen when you put the right tools in the hands of communities,” Trent writes on her website.

“So many donors … think that Africans can’t help themselves,” Frimpong says. “But we can help ourselves. We have everything [we need] to survive.”

The “Health Horizons: Innovation and the Informal Economy” column is made possible with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation.

M. Sophia Newman is a freelance writer and an editor with a substantial background in global health and health research. She wrote Next City's Health Horizons column from 2015 to 2016 and has reported from Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Kenya, Ghana, South Africa, and the United States on a wide range of topics. See more at msophianewman.com.

Follow M. Sophia .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)