To one person who lives in St. Louis, a pine grove in Forest Park is the real attraction in the shadow of the World’s Fair Pavilion. Another St. Louisan dreams of a revitalized Black Wall Street down the historic Martin Luther King Drive when they see the city-boosted Washington Avenue Historic District.

A group of researchers wanted to access the truth of what people value and remember most about St. Louis, without assuming publicly acknowledged symbols of the city — like the World’s Fair Pavilion, or the historic district, or even the city’s famous Gateway Arch — mean anything to them. So they began by letting residents decide what’s on the map.

“In my design studies, I think about what you would call the vernacular architecture — vernacular space,” says Allison Nkwocha, a graduate researcher with the public art-focused Monument Lab. “Monuments are often so grand and specific. They’re ‘heroes.’ They don’t really have that much to do with everyday people.”

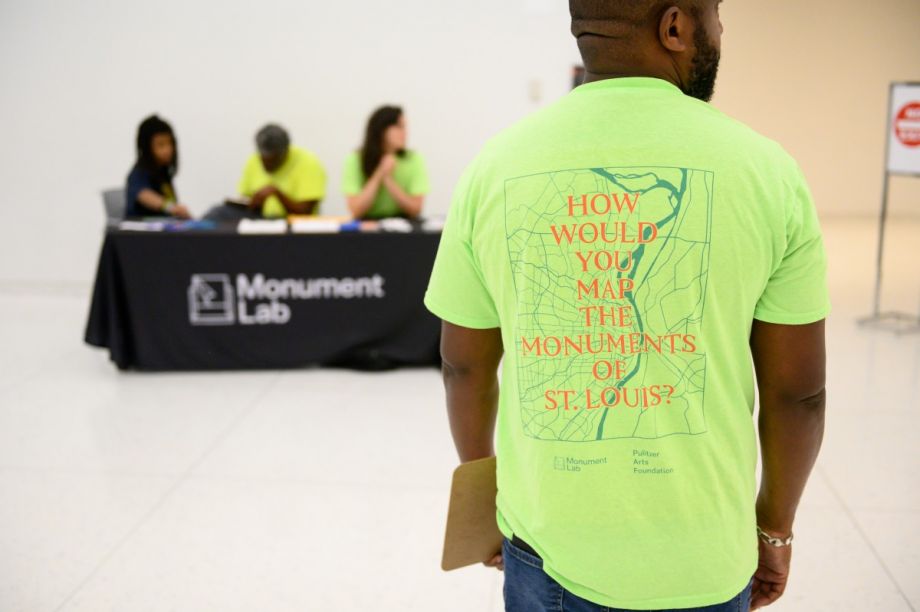

Nkwocha helped interpret 750 maps hand-drawn by residents of St. Louis for Public Iconographies, a collaboration between the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, Monument Lab, and community stakeholders in the city. There were two goals: First, to let residents define what a map of the city even looks like, and freely express their relationship to parts of St. Louis most important to them; and then, to present that data in a way that would channel the freeform responses, yet be legible and influential to decision makers in, say, a public art planning meeting.

The team translated all kinds of reflections into the visual language of traditional maps for this overarching report of events and places most honored in the city — whether or not those events and places are already served with a monument or marker.

Kristin Fleischmann Brewer, Pulitzer Arts Foundation’s deputy director of engagement, was thinking about the impulse to destroy objects deemed sacred by political and religious authorities when she called Monument Lab in 2018. The exhibition Striking Power: Iconoclasm in Ancient Egypt was taking shape at the museum. Fleischmann wanted to engage St. Louisans around similar questions raised in the show as a kind of counterpoint. The exhibition was about the destruction of sacred symbols, and the adjacent project would be about deciding which symbols are sacred.

“Even though it was about Egyptian art, the core of the show’s curatorial arguments was about iconoclasm and forms of iconoclasm and power, and narrative and storytelling,” Fleishmann said. “We’re always looking for ways to make these exhibitions meaningful and relevant to the larger community.”

So Fleischmann Brewer invited Monument Lab’s Kristen Giannantonio and Paul Farber to the city for intensive site visits, and they talked about what they might do together related to public memory.

“They met with influencers, people in public art, public space, academics, activists, and nonprofits that were grappling with problematic monuments that they were responsible for,” Fleischmann Brewer said. (This group included the leadership at Tower Grove Park, where a statue of Christopher Columbus came down two years later.)

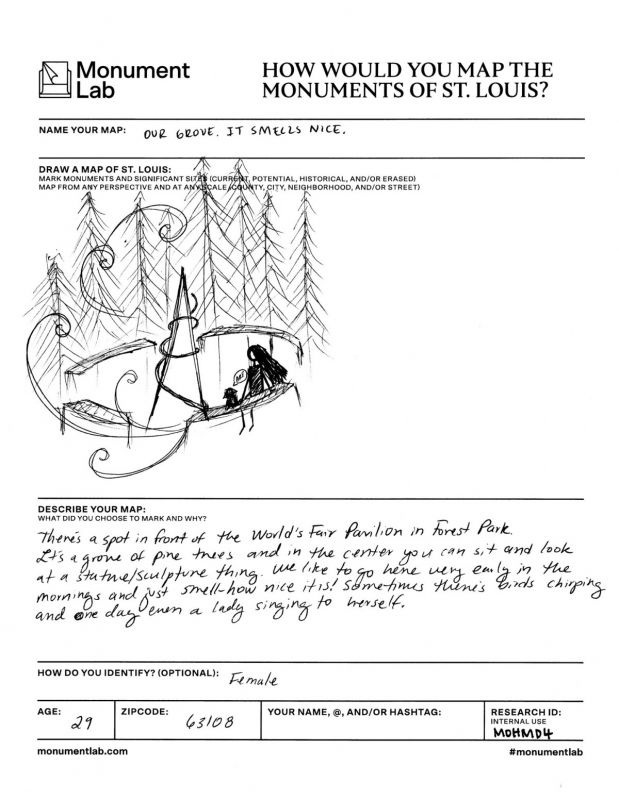

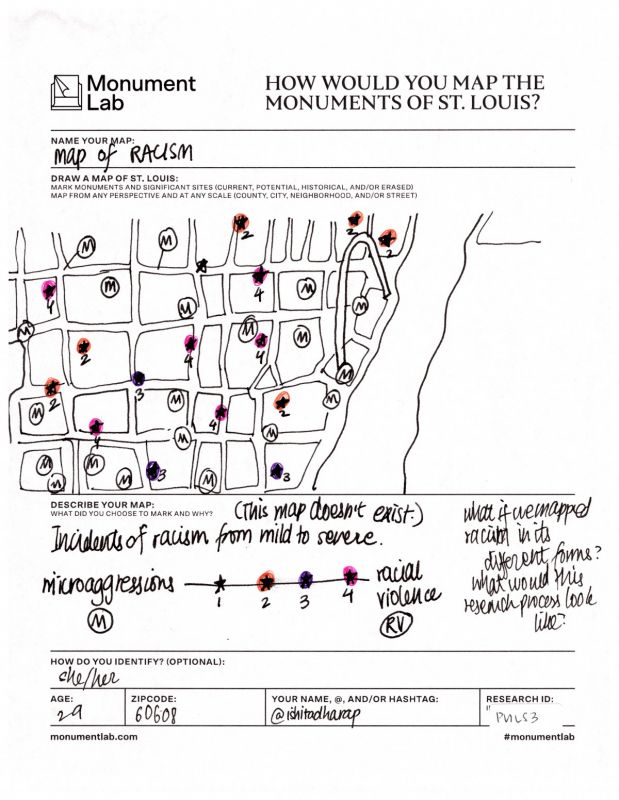

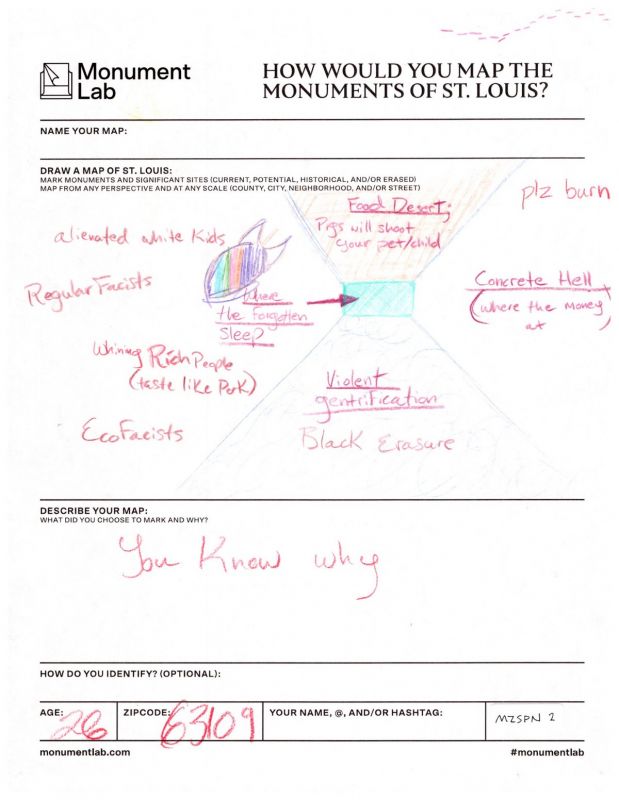

The mapmaking project Public Iconographies was born of these discussions. It would run at the same time as the Striking Power exhibition, extending from a dedicated room at the museum into the streets of St. Louis to source maps from attendees at 46 different events. Instead of asking participants to mark their ideas on a map of the city, organizers gave residents an open space on paper to draw their responses to this carefully worded prompt: How do you map the monuments of St. Louis?

Gallery: Public Iconographies Maps

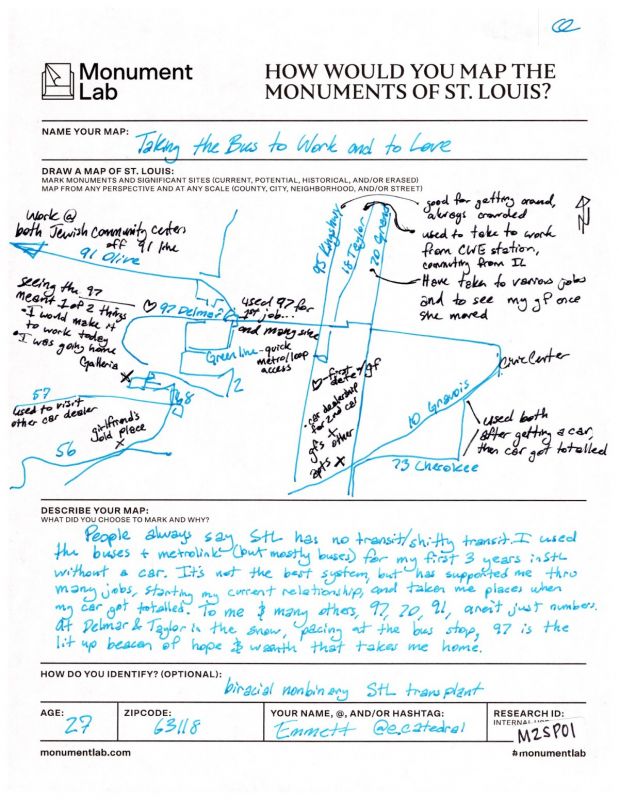

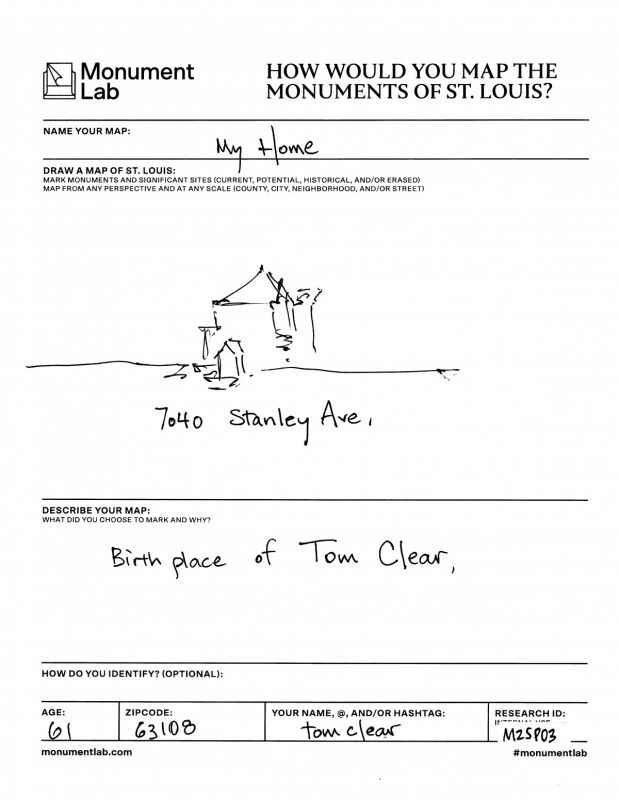

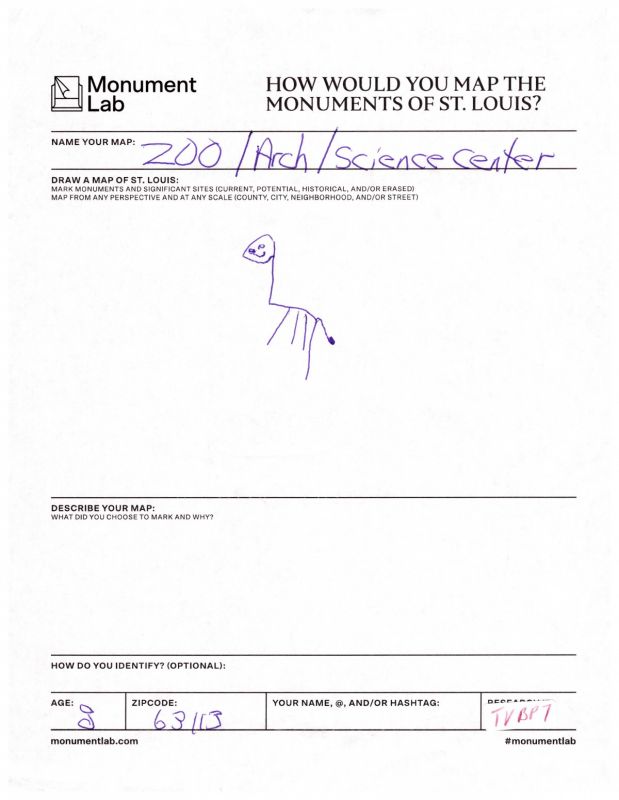

There was also a space to name and describe the map with words. Versions of “I can’t draw, so…” sometimes prefaced sketches of an elephant from the city’s zoo or attempts at the Mississippi River as seen on postcards of St. Louis. Other responders left the page teeming with vivid illustrations in color of artists beloved to the city like the performer Josephine Baker and sites of memory like the Cahokia Mounds, an echo of pre-Columbus native St. Louis.

Sites of mourning in and outside the city were referenced too, like the place in Ferguson where a police officer murdered Mike Brown. One participant acknowledged an area in St. Louis of “Violent gentrification” and “Black erasure,” and another where “Pigs will shoot your pet/child” and labeled a shaded rectangle with the words “where the forgotten sleep.” In the description field they wrote, simply, “You know why.”

“The point is to give people the ability to define what they are talking about,” Nkwocha says.

Important, too, was the invitation for people to define themselves. There were no boxes to check for race or ethnicity. Instead, along with an option to leave their age and zip code, people were given another blank space to answer the question: “How do you identify?” It’s not just what people drew, but how those people described themselves, that helped create the full picture for researchers so they could make decisions about what to emphasize.

“This process was not designed to be definitive or comprehensive, but we believe it captures ways of seeing things that many other forms of official data collection leave out,” says Laurie Allen, senior research advisor for Monument Lab.

The research team took each map collected and assigned a unique identifier to the form, Allen explains, which refers to that particular map across all data systems. After scanning the paper maps to create digital images, they transcribed text fields from the form into Airtables and then added each site identified on the hand-drawn map to a separate inventory of all the places mentioned by mapmakers. This data can be downloaded for re-use here.

Monument Lab researchers collaborated to produce the final interpretation of the paper maps responses. This overarching map has lots to tell about present-day St. Louis, via sites like the 24:1 Cinema in Pagedale, named for and part of a fascinating community development effort led by residents in the Normandy Schools Collaborative area. Proposed monuments without a site attached to them, like one participant’s idea for a 1917 Race Riots Memorial, appear with blue stars. Any spot mentioned more than 14 times is marked with an orange star; these locations are as specific as the location of Ted Drewes Frozen Custard, an 80-year-old custard stand and Christmas tree seller, and as generic as “Downtown.” If a participant used the words “Black” or “African American” to describe their map, then any location on it is marked with a yellow highlight. Sites of personal memory are marked with pink hearts — not unlike the one drawn by a child in one map, atop the Gateway Arch, and by many other responders in expressing feelings about personal memories made in the city.

Nkwocha illustrated callout icons for the final map. These represent eight sites of interest like Hop Alley, the Chinese immigrant community demolished by the city of St. Louis in the 1960s to make way for Busch Memorial Stadium. These individual cases were chosen not because of the frequency with which they were mentioned in the reponses, but because of the special emphasis placed on them by responders who did mention those sites, and other factors one could only consider by spending intimate time with the scans of every paper map.

“Out of the 1044 unique sites, we were drawn to these ones in particular because of the ways that people described them in writing and arranged them in drawings,” Nkwocha says. “Every word that appeared on each form became digital data in our tables, but referring back to the hand-drawn map to read it there reanimated the information and contextualized it within the little artifact of the maker’s world that is the paper map.”

Though the final map is distinctly thought-provoking, the relationships built through Public Iconographies could be just as influential, Fleischmann says.

“We have this monuments-and-public-memory group of minds,” she says. “We all know each other and we’ve all come together for various reasons since the official close of the residency [in August 2020], but all these relationships have stayed and they are snowballing into other projects.”

The museum is now particularly focused on supporting social justice movements in the city. Pulitzer Arts Foundation will soon welcome Jordan Weber as an artist in residence in collaboration with Washington University. Weber will continue his inquiries into mass incarceration and environmental justice with a focus on the Workhouse, a medium-security prison in St. Louis condemned by residents for inhumane treatment of prisoners. The city promised to close it last year but officials have yet to make good on that promise.

This story is a part of The Future of Monumentality, a series exploring the role of monuments in public space in the 21st century. This series is generously underwritten by the High Line, a nonprofit organization and public park on the West Side of Manhattan whose mission is to reimagine the role public spaces have in creating connected, healthy neighborhoods, and cities.

Lyndsay Knecht is an arts writer based in Texas. As associate producer for KERA 90.1, Dallas' NPR station, she launched the online editorial presence of Think with Krys Boyd. Her work has been heard on Monocle 24 radio, in Southwest the Magazine, Texas Monthly, the Tulsa Voice, The Dallas Morning News, the Texas Observer, Bustle, and other publications.

_920_518_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)