In August of 2020, in the midst of the pandemic, the number of unsheltered people in Saint Paul, Minnesota, rose to 380. The seasonal high, previously, had been 26. “It was a whole new world,” says Travis Bistodeau, the city’s deputy director of the Department of Safety and Inspections. “Even when we were managing the 26, it felt like an unfunded mandate that we were doing.”

The crisis forced the city into high gear to forge new partnerships and develop a comprehensive strategy for its unsheltered residents. One tool, which emerged as part of an 18-week “sprint” through the TOPcities program, is an app designed to address the current decentralized support system by providing a centralized platform for unsheltered residents to search and learn more about essential services.

“Information sharing was a major gap that was hindering everybody, including the city and outreach providers,” Bistodeau says. “There’s a significant subset of the unsheltered population who have cell phones and would love to know what’s available or where to go, but no tool to help them.”

Prior to COVID-19, the city didn’t have a complete or holistic approach or a dedicated agency to serving unhoused residents, according to Bistodeau. Previously, the city responded to complaints about people living in tents by telling those people to leave and removing their tents, under quick timelines and with little coordination with outreach or shelters. “It really was detrimental to the unsheltered folks — we were just chasing them further into the woods, which makes their lives more difficult and harder for outreach providers to find them,” he said.

When the pandemic hit, Saint Paul shelters reduced their capacity limits to adhere to social distancing rules, causing the unsheltered population to spike. It was clear the old, decentralized way of serving this population wouldn’t work. “The highest levels of our leadership, within a couple months of the pandemic striking, were out in the field trying to get a better understanding of what was happening and why,” Bistodeau says.

That summer, an opportunity arose to participate in TOPcities, an 18-week “innovation sprint” sponsored by the Centre for Public Impact, Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation at Georgetown University, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and Google.org, Google’s philanthropic arm. The idea was to facilitate partnerships with local governments, community and tech partners to develop tools responding to pandemic-related challenges. (The second city that participated, San José, developed a tool to address its looming eviction cliff.)

Saint Paul city officials partnered with M Health Fairview, a partnership organization between the University of Minnesota, University of Minnesota Physicians and Fairview Health Services, to tackle one big issue: Unsheltered people had no centralized resource to identify up-to-date support services.

“The idea was not to create a solution, but a tool that would make accessing resources easier for people that needed them,” says Naomi Alemseged, a project coordinator for M Health Fairview.

The team evaluated existing public data on services for unsheltered residents, interviewed 30 service providers and unsheltered residents to learn more about their challenges, held a focus group and conducted a survey in order to better understand the barriers and opportunities within the service delivery system.

“We heard a lot about difficulties with access [to shelter beds], people didn’t know if they could bring items, if it was for men or women, logistical questions people didn’t have access to,” explains Alemseged. “But we did learn that a lot of unsheltered people have smartphones … most people did have a way to access the internet.”

On top of a decentralized system that made it difficult to know where to go for services, there was a desire for greater autonomy to access services related to specific needs as well as up-to-date information on service availability.

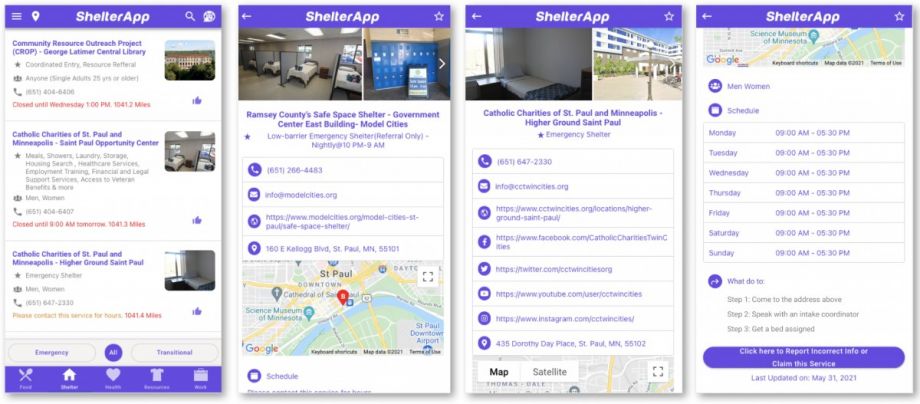

A centralized resource hub, the team posited, could offer information on short-term services like low-barrier shelter beds — with a priority on providing up-to-date information on bed availability — as well as lockers, meals and laundry. In their research they came across the all-volunteer, non-profit service ShelterApp, which already provides mobile and web resources to unsheltered and low-income residents in cities around the country. ShelterApp agreed to open-source its code so the team could create a Saint-Paul-specific version.

The team tested ShelterApp with service providers and residents, creating modifications like providing photos of the city’s shelter spaces and adding step-by-step directions on how to access a bed upon arriving at a shelter.

Currently, you can search for local resources including food, shelter, health and work through ShelterApp’s mobile and web platforms. The team will continue to build out the service, with a priority on providing real-time shelter bed availability and ultimately access to low-barrier housing by booking through the platform. The team is also working with greater Ramsey County’s Continuum of Care team to highlight expanded services across the county.

There’s no user data on ShelterApp yet, but Saint Paul is seeing the impact of its more holistic approach to serving unsheltered residents, which includes intensive outreach and expanding the supportive services available. As of October, the city was aware of approximately 23 individuals sheltering outdoors now, according to Bistodeau, with at least 65 people who have secured long term housing.

“ShelterApp is one tool that is addressing one of the needs we’ve identified through this crisis over the past year-and-a-half or so,” Bistodeau says. “What we’ve built, and any additional tools we can add, will continue to feed a model that better supports folks in the future.”

This article is part of Backyard, a newsletter exploring scalable solutions to make housing fairer, more affordable and more environmentally sustainable. Subscribe to our weekly Backyard newsletter.

Emily Nonko is a social justice and solutions-oriented reporter based in Brooklyn, New York. She covers a range of topics for Next City, including arts and culture, housing, movement building and transit.

Follow Emily .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)