When former California Governor Jerry Brown became mayor of Oakland some 16 years after leaving statewide office, he pledged to add 10,000 residents to the city’s downtown. Had Brown been the mayor of, say, booming Plano or Aurora, he could have spent his first term back at the Buddhist monastery where he once lived and the city would have reached that goal of its own accord.

This was, of course, the mid-2000s. Across the bay, San Francisco probably could have doubled in size were it not for the city’s restrictions on growth. Today it can hardly house all the Google employees who take the nerd bus from the city to Mountain View every day, much less the 800,000 others who cram into its 47 square miles.

Thirteen years after Brown’s first mayoral inauguration — and 36 after his original gubernatorial stint — Oakland has welcomed nearly all of those 10,000 hoped-for downtown residents. New high rises ring Lake Merritt, a tidal basin near downtown, and the Uptown district has replaced drug-infested empty lots with handsome mixed-use apartments, including affordable and market-rate housing. Meanwhile a new California industry, legalized (medical) marijuana, had sprouted its first trade school in downtown Oakland: Oaksterdam University.

Uptown’s Fox Theater, a 1920s movie palace, had by the mid-1970s become known as “the largest outdoor urinal in the world.” In March of this year, Bob Weir, the Magnetic Fields and Willie Nelson all played on its restored stage. A charter high school dedicated to performing arts is attached to the theater.

“The Uptown neighborhood of Oakland has to be listed as one of the great redevelopment success stories in California,” said Gabriel Metcalf, executive director of San Francisco Planning and Urban Research, a land use think tank. “It has brought life back to that part of downtown Oakland and it is now one of the great urban neighborhoods in California.”

Even the Golden State Warriors have escaped the NBA’s cellar, and native son MC Hammer is out of bankruptcy. Life in the Bay Area’s stepsister city — an industrial port town with historically high rates of poverty, drugs and gang activity — has been looking up, and many credit Mayor Brown.

“Jerry had a very clear idea of what he thought the city needed and he needed and he went about pursuing that,” said Oakland-based land use consultant David Rosen.

Oakland being Oakland, none of these changes took place on their own. When Brown breezed in with grand proclamations, he knew full well that he would seek help from a source familiar to roughly 400 of California’s 600-plus cities: The state’s redevelopment agencies.

In the arcane world of public finance, the power wielded by the Oakland Redevelopment Agencies, and its peers across the state, ranks nearly in a class by itself. In California, as in the 48 other states that use versions of it, local entities harvest the so-called “tax increment” that arises in areas designated for redevelopment. As property values rise, a certain portion of the property tax increases get reinvested into further redevelopment in the designated area, rather than going to the general use fund that typically captures property tax dollars. The whole arrangement is known as tax increment financing, or TIF. Redevelopment agencies do not directly develop property, but they do nearly everything else: They create redevelopment plans, fund local infrastructure improvements, assemble parcels, assist developers, broker deals and sell bonds to pay for all of the above.

In other words, redevelopment agencies mint money for cities.

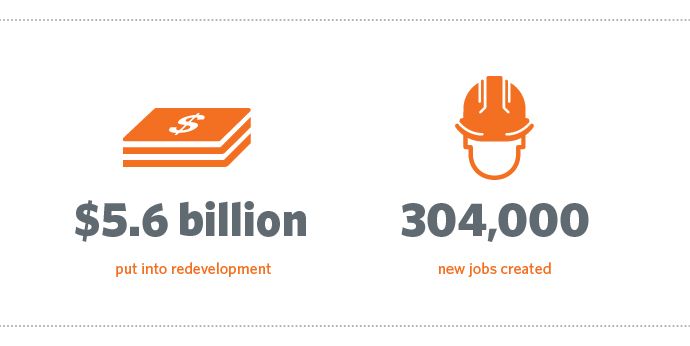

The idea is to create a virtuous cycle that means Napa Valley Chablis is now for sale in places that were, relatively recently, crack dens. This system worked so well that, by 2011, redevelopment project areas — some covering tens of thousands of acres — accounted for 12 percent of the state’s total property tax rolls netting over $5.6 billion in tax money annually, with most of it going right back to cities, to the delight of mayors such as Brown.

Claudia Cappio, director of Planning, Building and Major Projects under Brown in Oakland, gives a great deal of credit to the city’s redevelopment agency and the funds that it put into projects like Uptown and the Fox Theater.

“They played an important part in the city’s ability to match public improvements that would be commensurate with the investment from developers in the 10K housing effort,” said Cappio.

But when Brown became governor for the second time in January 2011 — 28 years after completing his first two terms, and three years after leaving Oakland City Hall — one of the first actions that Brown took was to declare the end of the very program that had helped the city, long the object of unabashed derision (such as Gertrude Stein’s inescapable “there is no there there”), get its game back.

In a 1978 article for Rolling Stone magazine, journalist Mike Royko inadvertently bestowed upon Brown the name “Governor Moonbeam,” in reference to his prowess at attracting the New Age vote. At the time, it was a major consistency in California. Royko, since deceased, has said that he regrets the name’s indignity and has in fact apologized publicly to Brown.

But even if Royko’s recantation has failed in the public mind, Brown’s new attitude might do the trick: Gov. Moonbeam has become Gov. Pragmatism.

The $26 billion budget deficit that Brown inherited from former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger left precious little room for flights of fancy. It arose in part from the state’s disastrous housing crash, which has left some communities riddled with foreclosures and in part from a notoriously ineffective budget-setting process in Sacramento.

Viewing redevelopment from the Capitol rather than from City Hall, Brown did the math.

Using his executive powers, he would simply do away with all of the state’s redevelopment agencies, which are the local bodies — sponsored by their respective cities and, in some cases, counties — that create the plans for redevelopment project areas and administer the TIF funds that come in. No agencies, no TIF, no $5.6 billion disappearing into 400 black holes.

Needless to say, those black holes were not happy.

From cities’ perspective, there’s no other way to describe redevelopment than as a cash cow. Though TIF monies were earmarked only for redevelopment-related activities — and were officially governed by redevelopment agencies and not by city governments — they were still a major infusion of cash. They were the only consistent source of funding for local economic and real estate development.

And, best of all, they came with limited state oversight. Agencies were required to spend 20 percent of their increment on affordable housing. But even that rule got bent all the time, with affordable housing funds often socked away for years. Otherwise, cities could use tax increment funds on everything from building bridges and sports stadiums through direct expenditures to assembling properties and brokering deals on behalf of private developers. Some cities, especially small cities, even used redevelopment funds to partially pay the salaries of employees who worked for both city and redevelopment agency. Few people in Sacramento knew what they were doing, or cared. And all Brown cared about was the $5.6 billion.

“In a lot of ways, he’s being realistic,” said Los Angeles-based land use consultant Larry Kosmont, whose firm has consulted with several cities on the shutdown of their RDA’s. “If I was sitting in the governor’s office and saw a $5.6 billion pile of money, the fact that I used it when I was as a mayor has very little to do with the fact that I need it when I’m a governor.”

Brown has been anything but remorseful, saying at times that redevelopment was of dubious value and saying on Jan. 18, “I don’t think we can delay this funeral.”

In fact, not only did the funeral go ahead as planned, but the grave was dug far deeper than anyone expected.

In many ways, the death of redevelopment was inevitable. Brown’s decision, backed up by the Supreme Court, was the atomic bomb detonated at the end of a six-decade war of attrition that had been waged on the balance sheets, in the statutes and, several times, in the voting booths of California.

State sponsored, TIF-aided redevelopment started out modestly enough in the urban renewal era and operated below Sacramento’s radar for decades. It’s hard to overstate how arcane California’s system of redevelopment became. It could appeal only to people like Peter Detwiler, the recently retired chief consultant to the Senate Governance and Finance Committee, whose bemusement over California’s system of government is matched only by his encyclopedic understanding of it. To hear him tell it, redevelopment law wasn’t mere sausage making. It was, to abuse the metaphor, what happens when sausages collide.

Redevelopment in California first arose in 1945 and was codified more formally in 1954. In those early decades, aligned with federal “slum clearance” and “urban revitalization” policies, redevelopment often consisted of the obliteration of blight, such as that which supposedly plagued Bunker Hill, a little piece of San Francisco in L.A., with Victorian apartment houses lining narrow streets above the city’s civic center. Today, thanks to bulldozers wielded by the city’s redevelopment agency, all that remains of the old Bunker Hill is the Angels Flight funicular, rebuilt in the shadow of Class-A high rises.

Over time, redevelopment became a gentler tool, but one used with increasing frequency. By the mid-1970s, redevelopment agencies abounded.

The best — or worst, depending on who you ask — thing ever to happen to redevelopment was the 1978 passage of Proposition 13, California’s infamous “tax revolt.” Prop. 13 froze annual residential and commercial property taxes at 1 percent of their most recent sale price. In a state where assessed property values have generally risen ever since the first Rose Parade enticed eastern transplants to the continent’s edge, Prop. 13 gave homeowners a windfall while devastating cities.

Unable to count on perpetually rising property tax revenues, cities cut where their expenses were greatest: schools. In essence, the state government apologized to cities for what it considered the recklessness of the state’s voters by pledging to “back-fill” local coffers with money for schools.

Left with precious few ways to raise funds, cities created new redevelopment agencies and project areas at a torrid pace. Well more than half of the agencies in the state were founded after 1978. The total, statewide tax increment grew nearly exponentially, from $1.02 billion in 1989 (the first year with reliable records) to $5.6 billion in 2008. It topped $2 billion in 2001 and increased by roughly $1 billion every two years until 2008.

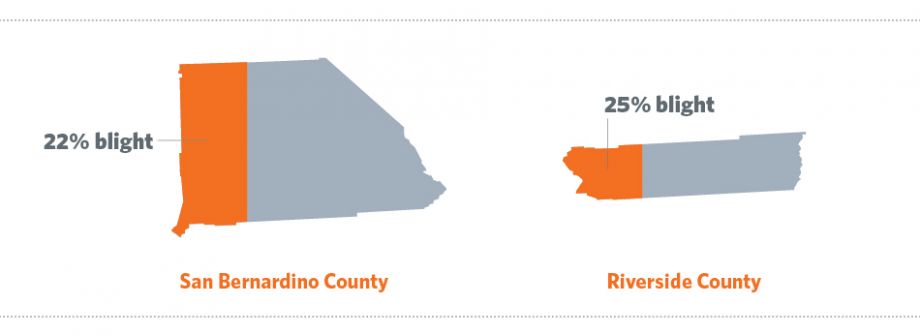

By 2011, an astounding 12 percent of total property tax receipts statewide were captured by cities through TIF arrangements. With little regulation of what could qualify as blight and thus be eligible for a TIF, some counties took redevelopment to extremes. In Southern California, the booming inland county of San Bernardino had, by 2004, classified 22 percent of the land within its borders as blight. By that same year, Riverside had declared blighted a full quarter of its land. Even rural counties like Yolo and San Benito — with hardly any urban areas, much less urban blight — got in the game, both going from zero percent blight in 1982 to 14 percent in 2004.

Along the way, golf courses, farm land, empty strips of urban fringe, city blocks sullied by a few wisps of graffiti, and parcels with just the slightest risk of flooding ended up being designated as candidates for redevelopment project areas. Eventually Sacramento noticed.

“The city of Diamond Bar declared the whole city blighted,” said Detwiler. “When the court stopped giggling, it said no.”

Over the years, Sacramento has tightened the definition of blight, and lawmakers imposed the 20 percent affordable housing set-aside. But ultimately, the numbers never worked out for Sacramento, because the greater the statewide TIF diversion grew, the more it had to back-fill from the general fund.

The formula worked roughly like this: When TIF gets diverted, roughly half of it comes from would-be school funds. Because statute binds the state to fully fund schools, Sacramento must fill in the shortfall created by the revenue rerouting. By 2011, this meant that the state was kicking in around $1.3 billion to make up for the diverted school revenue.

“There is no line item in the state general fund that asks, ‘do we want to spend $1.3 billion a year on the 400-some redevelopment authorities?” Detwiler said. “By operation of law it’s hidden. It’s not deviously hidden, but it’s simply built into our obligation to fully fund schools.”

The state first seriously took notice of this inequity in the mid-1990s under Gov. Pete Wilson. Wilson enacted the Educational Revenue Augmentation Fund (ERAF) by which redevelopment agencies were forced to contribute a share of their TIF monies to schools in their respective areas. And that’s where the escalation began. The more the state tried to increase ERAF payments, the more redevelopment agencies resisted, on the grounds that they had earned their TIF funds fair and square.

“Local officials felt double-crossed, and now we get into a story that begins to look like the Hatfields and the McCoys or the Montagues and Capulets,” said Detwiler. “In some ways the origins of the dispute are lost. It just becomes retaliation.”

In 2010, the redevelopment community thought it had fashioned a suitable shiv. California’s electoral system famously allows initiatives on virtually any issue to go on the state ballot and, if adopted, to become part of the state constitution. The CRA and League of Cities sponsored Proposition 22, which provided that the state could not appropriate funds from local entities in order to balance the state budget.

Prop. 22 passed, with 60 percent of the vote. The TIF was safe, at least until California slid into the ocean, or voters changed their minds. Or at least the redevelopment agencies thought so.

Two months later, Brown realized that if the voters had said he couldn’t appropriate funds from redevelopment agencies, he had one strategy left.

It’s hard to say how many projects have literally stopped in their tracks due to the governor’s decision. One of the incredible things about the multibillion-dollar industry that was redevelopment is that no one knows exactly what it entailed. The most recent study of agencies’ efficacy and business practices was a report that State Controller John Chiang published hastily in March 2011. It suggests that agencies do not always spend their monies wisely, and found that agencies often do not properly report their activities. Damning though the report may have been, its sample set was 18.

Whatever their books may look like, nearly every one of the state’s 400 redevelopment agencies can tell a story about crucial, transformative projects that are now threatened: Rehabilitated buildings, remediated brownfields, affordable housing developments, gleaming new parks, fire stations and even stadiums. To choose even a poignant random sample would not express the extent of the impact, or its variable effects on communities. One city’s mixed-use affordable housing development is as important as another city’s light rail maintenance yard. San Francisco’s $4 billion Transbay Terminal redevelopment surely rivals San Diego’s proposed NFL stadium.

After the governor dropped his bombshell, the redevelopment community wanted to protect its projects, staff members and funds. Several groups, including the California Redevelopment Association and League of California Cities, as well as a separate consortium of the mayors of the state’s 10 biggest cities, tried to broker deals. One compromise would have allowed agencies to make “voluntary” ERAF-style payments.

The CRA took a hard line, though, and rejected several proposed compromises the legislature had been more than happy to offer. Almost no one besides Brown ever wanted redevelopment agencies to go away. Even if Republicans in the state legislature were wary of government-sponsored development, they couldn’t support a Democratic governor. And Democrats had historically been champions of redevelopment precisely because of its benefits to poor communities. Therefore, the legislature took pains to defy the governor without actually defying the governor. None of it worked.

It was during these mid-summer discussions that CRA executive director John Shirey stepped down to become city manager of Sacramento.

The legislature’s ultimate solution was a pair of assembly bills, passed in August: AB X1 26 and AB X1 27. The former called for the dissolution of redevelopment agencies and outlined the procedure by which they would go out of business. The latter nullified AB X1 26 for those sponsoring jurisdictions — city and county governments — that agreed to return some of their TIF to the state. If all the state’s agencies agreed to the provisions of AB X 27, the total repatriated TIF would be, not coincidentally, around $1.3 billion — exactly the amount that Brown expected to net from wholesale elimination, once outstanding bonds and other obligations were met.

The two-bill solution was meant to get around Prop. 22 by making the payments “voluntary.” Some choice, said the redevelopment community. In fact, even though the bills were intended to help redevelopment agencies, they were not written with their cooperation. That’s because the redevelopment community all along rejected the notion of any kind of hindrance or transfer payments. They stayed out of the discussion in order to maintain the moral high ground for the fight that was to follow.

“Redevelopment agencies didn’t want to help write it because their ideology wouldn’t let them, so some of the deadlines and some of the procedures are real clunky,” said Detwiler. “They chose not to, so that’s what you get. You don’t play the game, you don’t make up the rule.”

A lawsuit that the CRA and League of California cities jointly filed in September 2011 contented that the two bills violated Prop. 22 and therefore should both be overturned, thus restoring the status quo.

“We were basically being asked to undermine Prop. 22,” said Julio Fuentes, city manager for the Southern California city of Alhambra and president of the CRA board. “I think in the end we didn’t have a choice.”

The Supreme Court had a choice, of course. In fact, it had four: It could nullify both, either or none of the bills. The plaintiffs were gunning for both. They would have settled for neither.

“What we pointed out to the court was that this two-bill strategy was a strategy to get around Proposition 22,” said Shirey. “It still stuns me that the court did not look at intent and did not recognize what the state was doing with AB 26 and 27 was to craft a scheme to get around the will of the voters in Proposition 22.”

One fact is indisputable: If the CRA and League had not filed their lawsuit, redevelopment would still exist. It would be hobbled, but deals would remain and projects would continue. Thousands of staff members would still have jobs. Shirey, who left the CRA in August 2011 to be city manager of Sacramento, might even still have his old job.

And yet, almost no one contends outright that the League and CRA made colossal blunders or points out the obvious: That in filing the suit and losing, they dug their own graves. That hesitancy may owe itself to political sensibilities. But observers may have expected that, one day, the redevelopment agencies would either stick it to the state or die trying.

As it turned out, the court handed down the redevelopment community’s worst-case scenario. A unanimous panel of justices held that 27 did indeed violate Prop. 22’s prohibition against transfers to certain local funds to the state general fund. But as the state’s lawyers argued, if Prop. 22 had been intended to prevent the state from disbanding redevelopment agencies entirely, its drafters could have included explicit language to that effect.

“I guess if we all had the hindsight that we had today maybe things would have been done differently,” said Fuentes. “But given the facts and circumstances that we had at that point I think we made the right call. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court didn’t feel that way.”

Throughout 2011, redevelopment agencies did something that they had never had to do in the previous 57 years since the formal establishment of redevelopment: They tried to explain to the public what they did and why they deserved to exist. It didn’t work.

Numerous surveys taken during this time indicate that redevelopment agencies’ lack of transparency, reported cozy relationships with developers and occasional but highly controversial use of eminent domain struck skepticism in the hearts of voters. And for every triumphant project that agencies trumpeted, residents suspected that there were untold thousands that conferred little, or no, benefit on their cities — or even worse, had an adverse effect.

But while public perceptions tended towards the cynical, some cities did manage to leverage TIF money in ways that helped their residents.

Before it became the home of the Internet and social networking billionaires, the Bay Area had been the industrial heart of the West Coast, with shipyards and steel mills ringing the bay. When those industries faded, they left places like Emeryville: Flat, toxic landfills with million-dollar views. Redevelopment money paid for environmental remediation, and from the 1980s onward the city implemented an aggressive plan to build apartment towers, retail, hotels and office towers, which have all sprouted proudly. It seems like half the Bay Area’s bachelor pads are furnished by its Ikea store.

“Emeryville was a post-industrial wasteland and we put in major infrastructure,” said Cappio, redevelopment director for the city from 1995 to 2000. She credits the city’s redevelopment agency, with its power of TIF, for making the transformation happen.

But successes like Cappio’s in Emeryville are, unfortunately, the exception. And the majority of project areas remain in various states of disrepair — as if after decades, the work of transforming communities may never be finished.

“Developers can bargain one agency against another.The net benefit for society for those arrangements is likely zero or negative.”

Not surprisingly, such state-sponsored redevelopment has long attracted ardent critics, especially among advocates of small government.

“The whole idea of government redevelopment is that the government can plan the type of development that should occur in a neighborhood,” said Timothy Sandefur, principal attorney with the Pacific Legal Foundation, which advocates for private property rights. “It’s politicians deciding when it ought to be producers and consumers…it ought to be builders and taxpayers who get to decide, not the government.”

The demise of California $5.6 billion annual experiment, however, sparked a more widespread — if belated — discussion about the efficacy of using TIFs and other methods of public financing.

Though redevelopment professionals readily point to cause and effect between redevelopment funds and new projects, critics question whether projects would’ve moved forward, even without the government assistance. They further question whether projects built in redevelopment project areas would not have simply been built nearby: Are states spending billions to subsidize business relocations?

“I think there is quite a bit of evidence that these local economic development programs are just moving things around,” said Helsley.

Indeed, while cities contend that the battle has always been between them and the state, it may be equally possible that the battle has been among cities themselves, with developers playing a monumental game of musical chairs.

“Developers can bargain one agency against another,” said Painter. “The net benefit for society for those arrangements is likely zero or negative.”

Painter says “likely” because redevelopment is notoriously difficult to study. Because every locality and every development is unique, researchers cannot run control experiments. For that reason, redevelopment — despite its multibillion-dollar consequences — is notoriously under-studied.

With “any intervention wherein project selection is not based on some kind of explicit criteria, it’s really difficult to determine what’s successful or what’s not,” said Painter. “And anything that has to do with regional activity is going to be challenging.”

The most widely cited study of California redevelopment is 14 years old. In 1998, Michael Dardia, then of the Public Policy Institute of California, now a deputy director at New York City’s Office of Management and Budget, concluded that California’s redevelopment agencies and their TIF arrangements created little value for all the money that they were spending. He found that in only four of 38 agencies studied did tax receipts grow fast enough to justify agencies’ commonly held claim that they are solely responsible for the incremental development that takes place in project areas.

Dardia further concluded that more than 50 percent of the land in most project areas was vacant, meaning that agencies were not so much wiping out blight as they were promoting new development.

For something with such dubious value, tax increment financing has a large, loyal following. Forty-eight other states have followed California’s lead in establishing their own TIF-powered redevelopment programs. California’s experience, does not, however, necessarily provide a cautionary tale for them. Other states have already, it seems, chosen different paths.

Marianne O’Malley, managing and principal analyst with California’s nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office, conducted a study comparing California’s redevelopment system to those in other states. She found that California cities relied far more heavily on it than cities elsewhere.

“In other states, it was a much smaller feature,” said O’Malley. “Typically the maximum length of a district timeline was a lot shorter” than in other states.

Additionally, other states do not set up the inherent rivalry between education and local economic development.

“We also found that oftentimes the affected local agencies would have to approve the creation of a TIF, and/or in some cases they were statutorily not permitted to use the schools’ share of the property tax,” said O’Malley.

Indeed, it appears that California’s was, shall we say, a unique system.

“Take any state — have Illinois or Ohio or Michigan or even Massachusetts put up $1 billion for local economic development — and you would have chambers of commerce dancing in the street,” said Detwiler. “No other state…spent $1.25 billion per year on local economic development with almost no state strings attached.”

Very few civic leaders in California are happy about its uniqueness now, however.

All lamentation aside, the actual dissolution of agencies is proving to be a monumental headache. Many city officials contend that the legislation ending redevelopment was poorly written, with clunky, unclear provisions for liquidating agencies’ assets and determining which projects in progress constitute obligations that the state must honor, even in the wake of the agencies’ demise.

The legislation includes what some consider vague language, and it does not offer much direction on matters such as the definition of “enforceable obligations.” Each former redevelopment agency will have an oversight board that will approve those obligations, but even then the state Department of Finance must approve of the boards’ lists.

Most expect that the result will be endless politicking over partially developed projects. For instance, the legislation does not necessarily pay for projects that have been designed but not yet built, meaning that potentially hundreds of millions of dollars in design work could be tossed out. Moreover, the auditor-controller offices in every county has to audit the books of each defunct redevelopment agencies, and the Department of Finance must scrutinize all 400 agencies all at once, delving into an area of law that is arcane even by real estate standards.

“There’s a whole series of very unusual, unique and almost unanswerable questions,” said Kosmont, the LA real estate consultant.

The obvious reason for AB X1 26’s shortcomings, such as they are, is that it was written without any expectation that it was going to be implemented. AB X1 26 was intended only to govern the wind-down of those agencies that opted out of the voluntary payments under the two-bill solution. That number had been expected to be minimal. But the court’s decision instantly made it the law of the land, warts and all.

“Now we’re dealing with the dissolution, uncertainty and confusion when you do something quickly and rashly,” said Kosmont.

The second issue facing California cities is that of long-term economic development. Not long ago, the idea that California would have to so much as bat an eyelash to compete against, and beat out, other states for business and migration would have been a punch line on the Tonight Show. But in the past decade, the California’s luster has faded, according to some measures — not least of which is the $26 billion deficit that kicked off the redevelopment chaos in the first place.

“In some number of years, cities will be deteriorating and they have no financial wherewithal to address those problems.”

Supporters of redevelopment contend that, far from a zero-sum game, tax increment financing is crucial for them to create an appealing, functional urban landscape. Otherwise, businesses that will have little trouble resisting California’s charms. Moreover, TIF is simply part of urban economics in the United States.

“The only other one that doesn’t (have TIF) is Arizona,” said Kosmont. “And, last time I looked, Arizona was mostly desert without high land prices.”

Opponents of redevelopment contend, however, that whatever its economic ramifications, the demise of redevelopment marks a significant moral victory for the state and its taxpayers. No longer will it be so politically easy, or convenient, for governments to use eminent domain. Historically, redevelopment agencies have used the state’s authority to seize property using the power of eminent domain far more liberally than other public bodies. Critics blame this on relative anonymity of these agencies — they are often unelected bodies that have little interaction with the public, and thus have little incentive to be accountable to the public.

These agencies are “unnecessary, wasteful, dubious, sometimes corrupt entities that exploit the power of eminent dominant in order to give it to politically well connected developers,” said Sandefur. Their end, he says, is a fantastic development for owners of property throughout the state, and to taxpayers.”

That view is rare among civic leaders, however. By and large, the consensus in California’s beleaguered cities is that the redevelopment process needed to be fixed, not thrown away.

“We need a break of about 3-5 years where we don’t have the winking and nudging and lying about blight, and state and local officials can get clean and sober on TIF spending,” said Detwiler.

Lawmakers in Sacramento are already discussing the prospects for a brand-new, reformed redevelopment program. Many proposals would do away with the troublesome notion of “blight” and replace it with redevelopment criteria geared towards more specific goals. One suggestion is for tax increment financing to align with Senate Bill 375, California’s 2008 law that promotes compact and transit-oriented development for the purposes of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

If nothing happens, cities will of course be free to pursue their own economic development strategies and to encourage whatever development they see fit. The trouble, however, is that they will not have $5.6 billion with which to do so.

From his vantage point in the statehouse, Jerry Brown has said little about the chaos that has engulfed his former counterparts and colleagues across the state. He has tepidly referred to the merits of redevelopment “such as they are” and said nothing substantive since his “funeral” comment two weeks before the dissolution deadline.

Observers in Sacramento say that the governor shows little appetite for reviving redevelopment. In a recent speech to an anxious audience of developers in Los Angeles, State Sen. Alex Padilla called Brown the number-one obstacle to a new redevelopment scheme. If Brown sticks to his position, the effects could be devastating for cities — especially Oakland and its peers.

“In some number of years…areas of cities, probably larger cities, will be deteriorating and they have no financial wherewithal to address those problems,” said Shirey.

But, as almost everyone in the state agrees, Brown has bigger problems. Gone are the days when a mayor in California could focus on building shining new apartments for 10,000 people or when a governor could contemplate sending up his own satellite, as Brown famously did back in those moonbeam days. Even things in Sacramento — the city, not the political maelstrom — have changed.

The first time he was governor, Brown, who at various times had both dated Linda Ronstadt and toyed with the idea of becoming a priest, famously slept on a mattress in a shoebox of an apartment near the State Capitol. He knew what he was missing out on, since his father, the legendary Pat Brown, resided in the governor’s mansion from 1959 to 1967. Jerry Brown is now married and older that his father was when he left office. Though not quite so spiritual or ascetic as he once was, Brown still lives in an apartment rather than the governor’s mansion. These days, however, the digs are far more upscale.

They’re in a converted loft apartment, in a building developed with — you guessed it — redevelopment funds.

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Josh Stephens is a freelance writer based in Los Angeles. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Planning Magazine, Sierra Magazine, the Huffington Post and the Los Angeles Review of Books. He is a contributing editor to the California Planning & Development Report and Planetizen. His website is joshrstephens.net.

Follow Josh .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

Tim Gough has been working in Philadelphia as a designer and art director for various agencies and design firms for the past eight years. His art is influenced by the screen printed process and mid-century graphics. In 2007, Tim left the agency life behind to pursue illustration and art full time. His work has been found in books, magazines, newspapers and other ephemera nationwide and abroad. Tim also publishes a limited-edition zine called ‘Cut and Paste,’ a collection of drawings and things. He frequently shows his drawings and screen prints in various galleries and shows.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine